Lincoln's Codebreakers

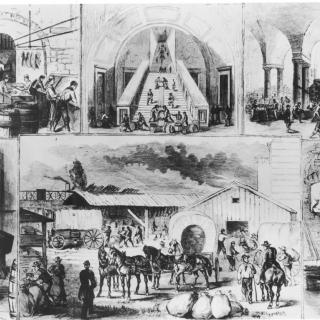

In a previous post, we looked at how President Abraham Lincoln utilized the telegraph during the Civil War to supervise his generals in the field and gather intelligence — sometimes by scanning telegrams intended for other Washington recipients. But in addition to working closely with Lincoln, the War Department's team of telegraph operators — who were based at the present-day location of the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, next door to the White House — also were pressed into service to perform another critical function in the war effort. They also worked as cryptographers, encoding sensitive communications for the Union side, and as codebreakers, deciphering intercepted letters sent by Confederate officials and spies.

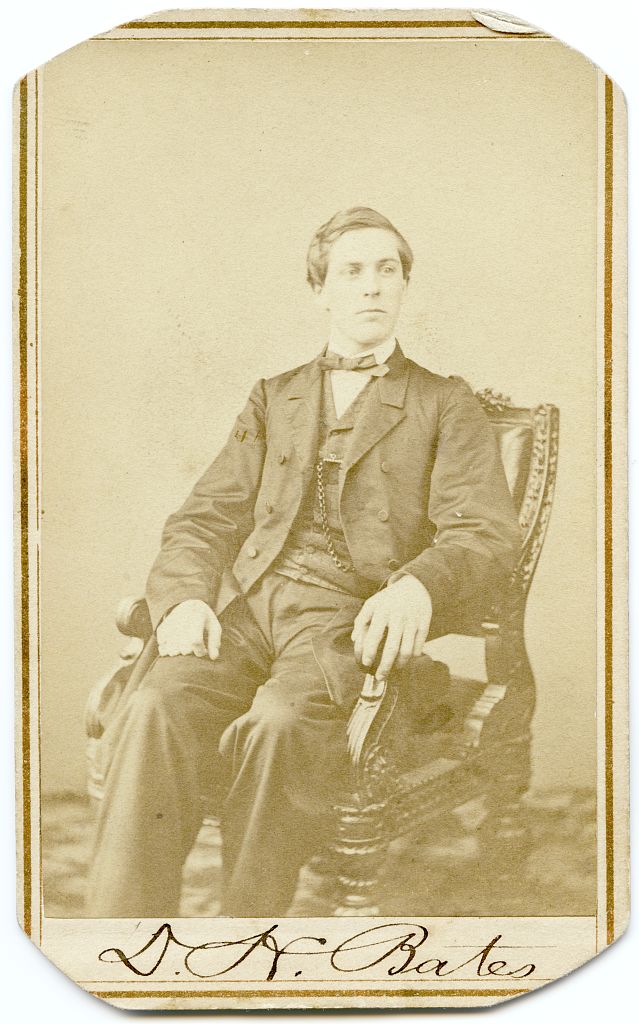

In an age when the federal government and the national security establishment was vastly smaller than it is today, David Homer Bates and three other operators — Thomas T. Eckert, Charles A. Tinker, and Albert B. Chandler — functioned as the 19th Century equivalent of the Fort Meade, Md.-based National Security Agency, which has an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 employees and an arsenal of supercomputers and other gadgetry at its disposal.

In a 1907 memoir, War Department telegraph office manager Bates describes both sides' efforts during the Civil War to intercept each other's communcations. During Union Gen. Ambrose Burnside's Fredericksburg, Va., campaign at the end of 1862, for example, the telegraph operators noticed an odd, irregular opening and closing of the circuit on the telegraph line connecting Burnside's Aquia Creek headquarters with Washington. "The characteristics of each Morse operator's sending are just as pronounced and as easily recognized as those of ordinary handwriting," Bates wrote. But this pattern didn't match any of the operators on the Union side, so they quickly realized that a Confederate spy had tapped the wire. In order to thwart him, Bates and his operators sent Burnside's headquarters a number of messages full of bogus information; the general or his operator, recognizing that something was up, in turn "sent us in reply a lot of balderdash."

Even as they did that, the War Department operators in Washington had another, real message of great importance that they had to get to Burnside. Lincoln planned to journey into the war zone to meet with him — a risky trip that, for obvious reasons, the Union side didn't want the Confederates to get wind of. Fortunately, they had a code system devised by a cryptographer named Anson Stager, which was so inscrutable that the Confederates never were able to crack it. Lincoln's message — "If I should be in boat off Aquia Creek at dark to-morrow evening, could you, with inconvenience, meet me and pass an hour or two? — was transformed into gobbledy-gook (A sample: "Can Inn ale me with 2 oarour Ann pas Ann me flesh ends N.V.")

In a show of wartime conviviality that would be unthinkable today, the Confederate spy — once he figured out that Bates and his team was onto him — actually got on the line and chatted with them for a few minutes, before disappearing just in time to evade Union troops sent to search for him along the wire.

The following year, the War Department's telegraph operators were called upon to decipher a letter intercepted by New York City's postmaster, Abram Wakeman. The letter was written by a man named J.H. Cammack, and was addressed to an Alex Keith, Jr. in Halifax, Nova Scotia. With Lincoln himself looking over their shoulders, the telegraph operators puzzled for hours over the message, which was in a hieroglypic-like Confederate cipher completely different from previous ones that they'd been called upon to break. Eventually, though, they did manage to crack it and a second letter sent by Cammack as well. As it turned out, Cammack was a Confederate gunrunner, and he was writing to Confederate government officials via Keith, to inform them about a bold plot to hijack a passenger ship leaving from New York harbor and use it to run 12,000 muskets through the Union blockade of the Southern coast. Armed with that information, Union officials arrested the would-be hijackers before they could strike.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)