Cross-Dressing Civil War Piracy on the Potomac

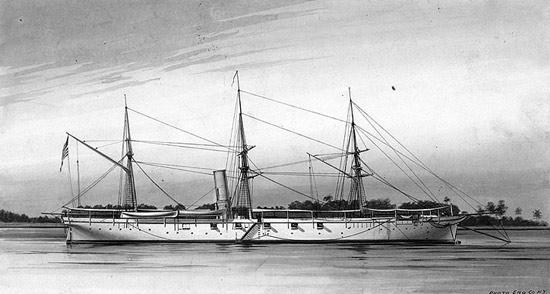

In the summer of 1861 the Confederate States found themselves annoyed by the U.S.S. Pawnee, a gunboat that patrolled the Potomac and made it difficult for the southerners to receive supplies from northern sympathizers. An idea was hatched to use the St. Nicholas, a supply steamer that was allowed to approach most Union ships unchallenged, to take the Pawnee.

One of the men behind the idea was Commander George N. Hollins, who’d served 46 years in the U.S. Navy, including under a stint under Stephen Decatur in the War of 1812. Hollins, who sided with the Confederacy during the Civil War, went to the Governor of Virginia, John Lechter, to gain his support. Lechter was on board and introduced Hollins to one Richard Thomas Zarvona, who claimed to have a plan to pull off the caper.

Zarvona made an impression on anyone who saw him. Described by some as “fragile in form,” he was known for wearing the military costume of the Zouaves, a distinct branch of the French military. The son of a wealthy and established Maryland family, Zarvona had attended West Point but dropped out to travel the world; he fought pirates in China, joined Garibaldi’s cause in Italy, and had his heart broken in France. Reportedly, he’d fallen in love with a French woman only to have her “expire in his arms” after drowning. In grief, he legally attached her name to his own, hence Zarvona. After the episode, Zarvona returned to the States and headed straight to Virginia with his “kindred spirit,” Lieutenant George W. Alexander, a former U.S. Navy engineer.

At their first meeting, Commodore Hollins was not so impressed with the slender, soft spoken Zarvona. Governor Lechter, however, was greatly enthused by the young man’s plan and even promised Zarvona the title of Colonel and Alexander the title of Captain if they succeeded in capturing the Pawnee. And boy, was it a great plan – reckless maybe, but pretty awesome. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves…

Lechter provided Zarvona with a letter of credit for $1,000 in order to procure men and arms in Baltimore. Hollins would wait for Zarvona’s return down the river at Point Lookout, a frequent stop of the St. Nicholas. Zarvona, already calling himself a colonel at Lechter’s suggestion, gathered about 15 men and they boarded the St. Nicholas on June 28, 1861.

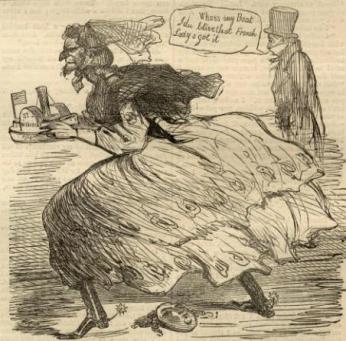

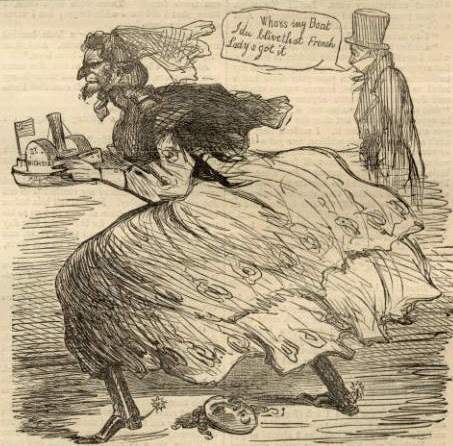

The men came in twos and threes, dressed as common laborers in order to avoid suspicion. They were searched by Union troops before being allowed to board but these searches only turned up normal tradesmen tools. So, they were let on the ship. The colonel, however, was nowhere to be seen… though there was a French lady who came aboard, calling herself a milliner and traveling with large trunks of hats to prove it.

Accounts of how this French woman looked and acted vary but one account paints an exciting picture. According to George W. Watts, who was aboard the ship, the French woman “flirted shamelessly with the most attractive males among the passengers and ship’s officers… She tossed her fan about and cocked her head at an angle toward any gentleman who occupied her attention.” She wandered from saloon to dance hall, behaving in such an outrageous manner “that all the other women in the boat were in a terrible state over it.”

The French lady even held a conversation, in French, with Captain Jacob Kirwin, who would later swear that he didn’t like the appearance of her one little bit. During this conversation the French woman also reportedly touched her leg against the captain’s, presumably sending the respectable women aboard into swooning fits. Some reports also mention a fierce-looking, bearded brother (in some accounts, her beau) who accompanied her about the ship and acted as her English translator when necessary.

The St. Nicholas stopped at Point Lookout and took aboard more passengers. Among them were maybe 15 more men prepared to take the ship and another innocuous passenger, an old man with a cane. This elderly gentleman met the French lady by chance and recognized her as an acquaintance from Paris. They struck up a conversation in French.

escapes with the USS Pawnee. (Source: Harpers

Weekly, July 27, 1861)

After midnight on the morning of the June 29, the three disguised leaders of the plot made a striking appearance on the deck of the ship. The lady revealed beneath her women’s clothes the form and dress of a man, Richard Thomas Zarvona. The older man and the bearded brother revealed themselves as Hollins and Alexander (accounts differ on which was which). The rest of their band pulled out the arms that Zarvona had hidden under the ladies’ hats and they quickly and bloodlessly took the ship, the whole thing taking no more than a few minutes.

Hollins took command of the vessel and directed her to Coan River, near the mouth of the Potomac. At an assigned meeting place, they picked up 100 Tennessee soldiers (this was less than agreed upon, since the Confederate Secretary of the Navy was really not keen on the plan). From here, they ought to have gone on to take the Pawnee but there was a problem: the Pawnee was nowhere to be found. Her captain (or a captain of another ship in the same fleet) had died and the Pawnee was docked in Washington for the funeral.

Though disappointed, the Confederates aboard the St. Nicholas were not going to return home without doing something to help their cause. So, they set their sights on other supply ships and netted the Confederacy a good amount of coal, ice, and coffee. They brought their ships and goods, the total cost of which was valued at $375,000 or $400,000, to Fredericksburg where they received a hero’s welcome. The St. Nicholas was then sold and then converted into a Confederate naval vessel.

That would’ve made a tidy end to the story, but Zarvona wasn’t quite ready to ride off into the sunset. Though warned by friends and strangers on every leg of his journey, the young colonel booked passage again to Baltimore hoping to snag another Union ship. This time, however, Union forces were ready for him. Aboard the Mary Washington, former officers of the St. Nicholas pointed Zarvona out to police officers. After briefly eluding them, the flexible colonel was found squeezed in a bureau drawer in the ladies’ cabin and captured.

After Zarvona was imprisoned on July 9, 1861, a legal battle began between the Union and the Confederate States. (Because, you know, the war was not enough.) The Union, loathe to let the colonel go, refused to classify him as a prisoner of war, which would have made him eligible for exchange and instead treated him as a felon. However, Union authorities also refused to put Zarvona on trial for a particular crime. Thus, he was kept in indefinite detention.

It wasn’t until April of 1863 that Zarvona was finally released, thanks to the efforts of Governor Lechter who negotiated an exchange of Zarvona for seven Union hostages with the understanding that the colonel would leave America until the war was over and do nothing to help the Confederacy.

Zarvona, still eager for action, asked his superiors immediately to be put in charge of some force to fight the Union. The honorable Virginians declined to break the terms of his parole, and besides, Zarvona was in no condition to go a-warring; his health was ruined from his years of ill-treatment. The young colonel left for France, “broken in body and spirit.”

After the war, the sickly Zarvona bounced back and forth across the Atlantic, trying bring himself and his family back from the brink of “financial disaster” (Union soldiers had pillaged everything of value from his family’s estate). He eventually died penniless and alone in 1875 in his brother’s home, believing that he’d been abandoned and forgotten by his wartime friends and supporters.

Although he would never know, Zarvona was wrong about being forgotten. There was an outpouring of grief at his passing. As the Tennessee Public Ledger put it:

He was insensible to fear… He universally sought the most hazardous undertakings and fearlessly exposed himself to the most formidable dangers. And yet modesty, candor and sincerity were marked characteristics of his nature. Gentleness, kindness, tenderness were predominant traits in his character. He was a sincere and devoted friend, a true and tried citizen, and a patriotic soldier.

All of us should be so lucky to have an obituary like that!

Sources

Evening Star. (Washington, D.C.), 02 July 1861. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1861-07-02/ed-1/seq-2/>

The Daily Dispatch. (Richmond [Va.]), 02 July 1861. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84024738/1861-07-02/ed-1/seq-2/>

The National Republican. (Washington, D.C.), 02 July 1861. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.<http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014760/1861-07-02/ed-1/seq-4/>

Edgefield Advertiser. (Edgefield, S.C.), 03 July 1861. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026897/1861-07-03/ed-1/seq-3/>

Daily Intelligencer. (Wheeling, Va. [W. Va.]), 13 July 1861. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026845/1861-07-13/ed-1/seq-1/>

Nashville Union and American. (Nashville, Tenn.), 18 July 1861. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85038518/1861-07-18/ed-1/seq-1/>

The Daily Dispatch. (Richmond [Va.]), 14 Feb. 1863. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84024738/1863-02-14/ed-1/seq-1/>

The Daily Dispatch. (Richmond [Va.]), 14 Feb. 1863. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84024738/1863-02-14/ed-1/seq-1/>

Public Ledger. (Memphis, Tenn.), 21 April 1875. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85033673/1875-04-21/ed-1/seq-1/>

Public Ledger. (Memphis, Tenn.), 19 Jan. 1878. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85033673/1878-01-19/ed-1/seq-2/>

Holly, David C. Chesapeake Steamboats: Vanished Fleet. Maryland: Tidewater Publishers, 1994. Print.

“Richard Thomas Zarvona,” The Latin Library website. Accessed 17 December 2013.

http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/chron/civilwarnotes/zarvona.html

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)