The Hanafi Siege of 1977

When Pierre L’Enfant designed the city of Washington, he structured the wide boulevards and traffic circles so that it could not be easily tied up by violence, as Paris had been during the French Revolution. Yesterday, it was obvious that L’Enfant failed.[1]

So read the Washington Post on the morning of March 10, 1977. But traffic was the least of Washington’s concerns that day.

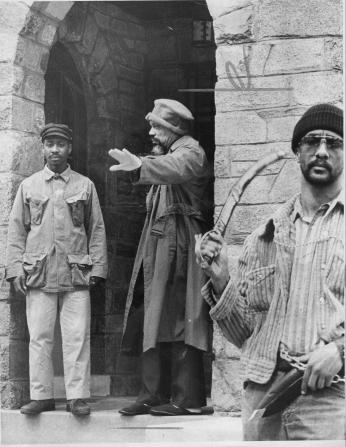

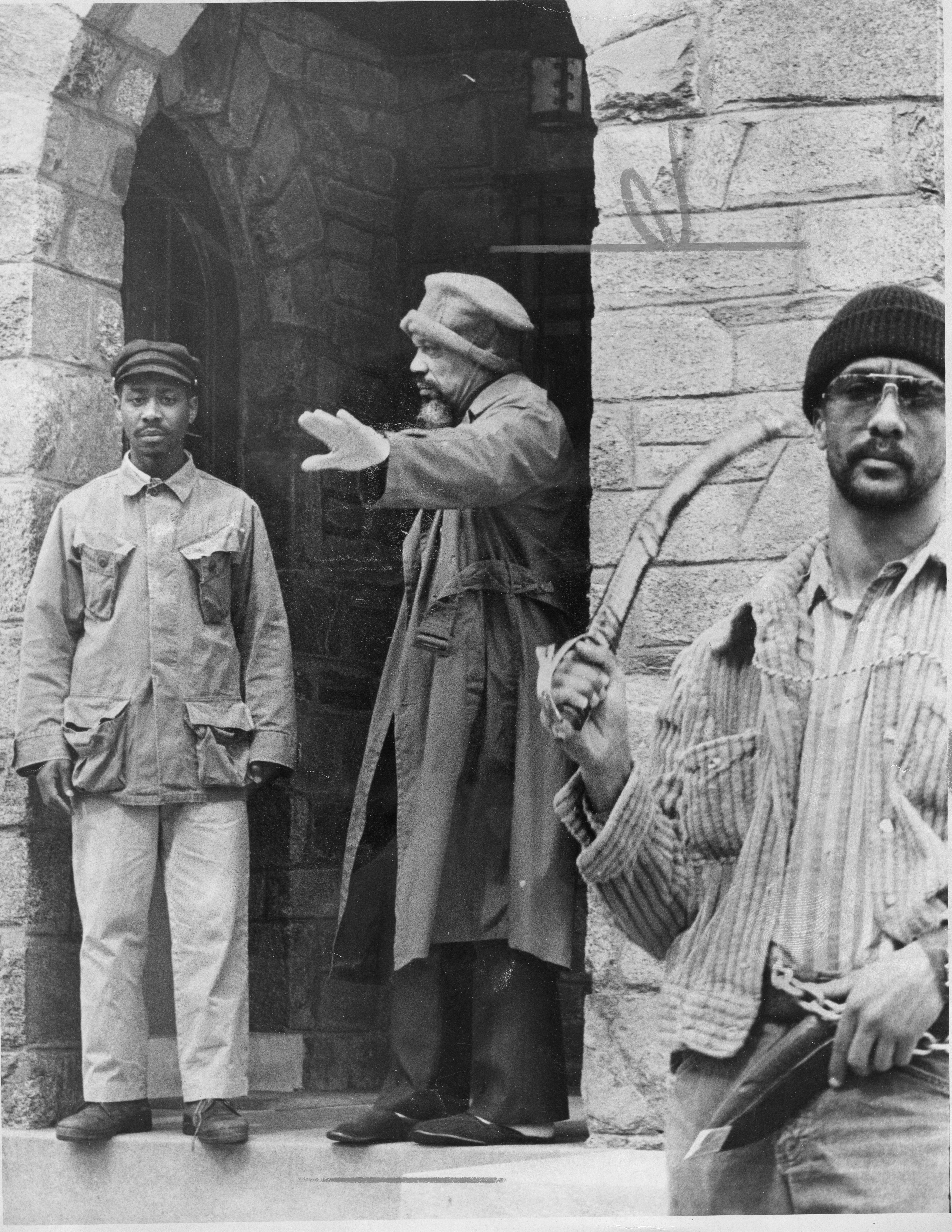

The previous afternoon, twelve armed Hanafi Muslim gunmen under the leadership of Hamaas Abdul Khaalis had stormed three different buildings in the city and taken nearly 150 hostages. The ordeal started at lunchtime at the B’nai B’rith headquarters on Rhode Island Ave. NW. About an hour later the group raided the Islamic Center of Washington on Massachusetts Ave. and then the District Building at Judiciary Square.

Several captives at B’nai B’rith were beaten and stabbed by captors who brandished machetes and guns. At the District Building, the gunmen killed WHUR reporter Maurice Williams and shot three others, including then-and-again city councilman Marion Barry.

With hostages corralled across the city, authorities struggled to restore order. Meanwhile, the aggressors promised more violence if their wishes were not met. As one of the gunmen at the Islamic Center told the Washington Post, “Everything’s fine. We’re all having coffee and tea and a nice chat. But heads will roll and people will die unless we get our demands.”[2]

So, what were the demands, exactly?

Well, first off, the group wanted to halt the release of the film, Mohammed, Messenger of God (also called The Message), which was set to premiere in New York and Los Angeles. As orthodox Muslims, the Hanafis objected to any pictorial representation of the prophet Mohammed (or suggestion thereof through shadows or artistic camera work). As Khaalis told reporters, “We have told this government that that picture is not to play in this country, that we will not stand for the mockery of our prophet and our Lord Allah, not while we live. Some Muslims must stand up.”[3] (Interestingly, the film did not actually portray the prophet.)

The other demands dealt with more personal issues for the Hanafi leader.

Four years earlier, Khaalis had returned from the grocery store to find seven members of his family brutally murdered at the Hanafi center on 16th St., NW. Khaalis attributed the crime to the Nation of Islam, which he had previously served (as national secretary) before splitting off from the organization.

(After the split, Khaalis had become an outspoken critic of the Nation of Islam and its leader Elijah Muhammad. He and some followers started a Hanafi Muslim community in Washington and setup a Hanafi Muslim Center in a Tudor style home on 16th St. NW, which was purchased for them by basketball star Kareem Abdul Jabbar, who had close ties to the Hanafi group.)

Following the murders, seven members of a Philadelphia temple affiliated with Elijah Muhammad were convicted and sentenced to prison but, as far as Khaalis was concerned, the investigation failed to fully expose the Nation of Islam’s role in the crime.

It seems that the siege – and the considerable media attention it attracted – was his way of correcting this perceived injustice. As he told the Post during the standoff, “We have told this government to get busy and get the murderers that came into our house on Jan. 18 [1973] and murdered our babies. And our children. And shot up our women…. Tell them the payday is here. We gonna pull the cover off of them. No more games.”[4]

Khaalis demanded that those convicted for the 1973 murders be handed over to him, presumably for execution. He also demanded that he be refunded $750 in legal fees that he had been forced to pay after getting a contempt of court citation during the murder trial of his children's killers.

And so, for 38 hours, Washington and the world waited to see what would happen. Crowds gathered on the street near the hostage locations and the media presence swelled.

Early on, three ambassadors from Islamic nations volunteered their services in negotiating an end to the standoff. And so, for hours, Ardeshir Zahedi of Iran, Sahabzada Yaqub-Khan of Pakistan and Ashraf A. Ghorbal engaged in phone conversations with Khaalis, urging him to be compassionate toward the hostages.

The Ambassadors eventually arranged to meet with Khaalis in person at B’nai B’rith, along with Metropolitan Police Chief Joseph O’Brien, who had earned Khaalis’s trust during the murder investigation four years earlier. The in-person discussions lasted three hours and, when they concluded, authorities expressed hope that the standoff could be ended peacefully the next day.

As it turned out, the end came much sooner. Shortly after midnight, Khaalis coordinated a surrender and release of the hostages at all three locations. The ordeal was over almost as unexpectedly as it had started.

Later that night, 3,000 miles away, a horde of bodyguards surrounded the court at the Los Angeles Forum, aiming to protect Lakers star Kareem Abdul Jabbar from anyone who might try to cause him harm, due to his connection to D.C.’s Hanafi Muslims. There were no incidents and Abdul Jabbar scored a game-high 31 points as the Lakers rolled to victory.

And who was their opponent that night? The Washington Bullets.

Footnotes

- ^ Ringle, Ken and Jack Eisen, “Seizure of 3 Buildings Ties Up Traffic in Heart of City,” The Washington Post, 10 Mar 1977: A18.

- ^ McCombs, Phil and Charles R. Babcock, “Gunman: ‘People Will Die Unless We Get Our Demands’: Islamic Center Mosque,” The Washington Post, 10 Mar 1977: A15.

- ^ “Tell Them Payday is Here… No More Games,” The Washington Post, 11 Mar 1977: A18.

- ^ Ibid.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)