Ezra Pound's Stay at St. Elizabeths

Throughout American history some of the most important Americans have lived in Washington, D.C., and mostly these people have been politicians, diplomats, or activists drawn to the capital for the proximity to the nation’s highest seats of power. But for more than 12 years, from 1946-1958, American writer Ezra Pound, a figurehead of modern literature, also called the District of Columbia home. However, rather than a Georgetown or Capitol Hill row home, Pound was a patient of the Chestnut Ward at St. Elizabeths Hospital in southeast D.C. after an arrest in Italy on charges of treason.

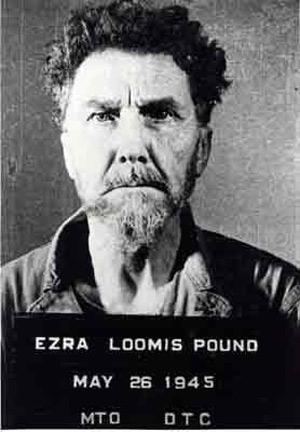

Pound was a central figure of the modernist movement, editing T.S. Eliot’s landmark poem The Waste Land and helping to get other modern writers published, including Ernest Hemingway and James Joyce. But part of what made Pound a controversial writer, and the reason he ended up in a D.C. mental institution, were his fascist leanings. In 1941, he began broadcasting for the Italian fascists out of Rapallo, Italy, where he voiced anti-Semitism and spoke out against the American military. Some of his praise for fascism even found its way into his 120 section life’s work The Cantos. In 1945, Pound surrendered to the Americans on charges of treason.

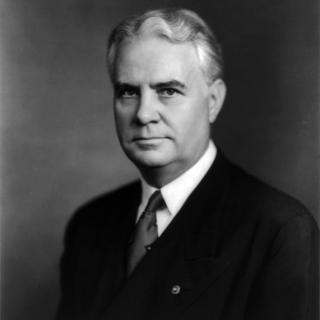

He pled insanity, but the doctors who assessed the poet found him to be of sane condition. However, the superintendant of St. Elizabeths at the time, Dr. Winfred Olverholser, who had a cultural fascination with the poet, protected Pound from criminal prosecution and a possible life sentence by crafting a testimony to have him treated as insane.[1] It stands as a clear example of abuse of psychiatry in criminal justice, but it worked, and in 1946 Ezra Pound was admitted into St. Elizabeths.

Today, outpatient treatment is legally recognized as the most helpful form of treatment for the vast majority of mental illnesses. However, in the 1940s/1950s institutionalization was the norm for the American mental health system, and crowding and the resultant poor conditions at mental health hospitals were common.

In 1945, the year before Pound was admitted, St. Elizabeths had reached its peak population of 7,450 patients, too many despite the hospital’s sprawling 130-building campus.[2] Besides Pound, other notable patients have included President Garfield’s assassin Charles Guiteau, Andrew Jackson’s failed assassin Richard Lawrence, “The Shotgun Stalker” D.C. serial killer James Swann, and failed assassin of Ronald Reagan, John Hinckley, Jr., who remains in institutional psychiatric care at the hospital today.

Literature scholar Robert E. Knoll visited Pound in 1956 in the Chestnut Ward, a wide corridor with a few rocking chairs, a TV, and cubicles for sleeping. He described the ward as “drab, drab, without color and with little light. . .”3 Despite 10 years in a crowded hospital, Pound himself appeared to be in good spirits, and he greeted Knoll with leftover mince pie and cheese out of a tin and served it on waxed paper and cardboard. Knoll wrote, “It seemed to me he looked like one who has just come from a game he plays very well, a game to which he knew he could soon return.”[3]

Ostensibly, the goal of Pound’s treatment was to treat whatever psychosis had caused his fascism-praising. Much later in life, Pound became regretful of his fascism and anti-Semitism, but while at St. Elizabeths he appeared to be very much unapologetic. Knoll claims that in conversation, Pound told him that he was not an anti-Semite, but that the poet then went on to say: “The trouble with these Jews is that they are good for only one generation. They ruin the next generation.” Knoll described Pound’s anti-Semitism as seemingly “dispassionate” and “born of conviction, not of the guts.”3 Pound scholar Dr. Wendy Flory believes that it was a delusion over a Jewish conspiracy that made the poet mentally unstable.[4]

When speaking against Jewish people or praising fascism, he seemed illogical, but when speaking on literature and the importance of words, Pound reasoned with a clear logic. He himself once wrote, “For when words cease to cling close to things, kingdoms fall, empires wane and diminish.”

Several American poets and writers, including Robert Frost, T.S. Eliot, and Ernest Hemingway worked for years to get Pound out of St. Elizabeths. In 1948, T.S Eliot and other jury members of the Fellows in American Literature of the Library of Congress awarded Pound the inaugural Bollingen Prize for his The Pisan Cantos. Pound wrote the Cantos while being held in an American prison camp outside of Pisa after his arrest in Rapallo. Controversy over awarding the highest prize in American poetry to a convicted traitor led Congress to disassociate the Library of Congress with the Bollingen Prize, which has since been awarded from the Yale University Library.

Robert Frost secured legal advocacy for Pound (despite Pound’s disapproval of the conservative writer) by recruiting the Washington law firm Arnold, Fortas & Porter to work pro bono on a motion for his release, and in 1955 Hemingway was quoted as saying “. . . Whatever he did has been punished greatly and I believe he should be freed to go and write poems in Italy where he is loved and understood.”[5]

Psychiatrists at St. Elizabeths did not believe Pound’s condition to have changed since 12 years prior when he was admitted to the hospital, but they felt that the 72 year old poet no longer posed any threat to others. In 1958, Pound was released from St. Elizabeths, and he returned to Italy. Upon disembarking he gave the fascist salute to the awaiting press.

Since his release, overcrowding at the hospital was improved, but other problems continued to plague St. Elizabeths. In 1988 the District of Columbia took over the hospital from the federal government, and since then measures have been taken to overhaul St. Elizabeths, including downsizing to a new, smaller $161 million hospital that opened in 2010. In 2013, the Department of Homeland Security opened new headquarters on the St. Elizabeths campus, and developers hope a new community pavilion on the east campus will anchor development and revitalization of some of the depressed Ward 8 neighborhoods in the surrounding area. While this new construction takes place mostly on the east campus, most of the west campus’s buildings still stand shuttered today, including Pound’s Chestnut Ward.

Footnotes

- ^ Mitgang, Herbert. "RESEARCHERS DISPUTE EZRA POUND'S 'INSANITY'" The New York Times, 30 Oct. 1981. Retrieved from: http://www.nytimes.com/1981/10/31/books/researchers-dispute-ezra-pound-…

- ^ Cauvin, Henri E. "New Building Could Mark New Era for St. Elizabeths Hospital." The Washington Post, 19 Apr. 2010. Retrieved from: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/04/18/AR20100…

- ^ Knoll, Robert E. “Ezra Pound at St. Elizabeth’s.” Prairie Schooner Vol. 47, No. 1, Spring 1973. Retrieved from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40628479

- ^ Cardona, Ellen. "Pound's Anti-Semitism at St. Elizabeths: 1945-1958." Flashpoint Magazine. Retrieved from: http://www.flashpointmag.com/card.htm

- ^ Action Set To Release Ezra Pound. 1958. The Washington Post (1955-1959), April 6, 1958. Retrieved from Proquest.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)