Baseball But No Palm Trees: Nats Wartime Spring Training

Ah, Major League Baseball Spring Training, the annual spring rite when ball clubs escape the cold of the north and go to Florida or Arizona to shake off the winter rust. Teams have been doing it for over one hundred years.

In fact, our hometown Washington Nationals began the trend – sort of – in 1888 when they became the first club to hold camp in Florida, setting up shop in Jacksonville. The experiment was a little before its time. When the Nats finished the 1888 season with a 46-86 record (a mere 37 and a half games out of first place), they and other teams decided traveling South to train was not a recipe for success.

It took a few years, but teams eventually reconsidered and – thanks largely to a sunshine state building boom – Florida’s Grapefruit League was well established by the 1930s. The Washington Senators camped in Orlando in 1936 and stayed there until 1960, except for a memorable three-year stretch during World War II.

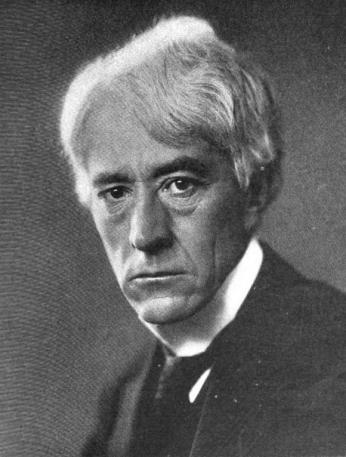

With the war effort in full swing, baseball Commissioner Judge Kennesaw Mountain Landis wrote to President Roosevelt in 1942: “The time is approaching when, in ordinary conditions, our teams would be heading for Spring training camps. However, inasmuch as these are not ordinary times, I venture to ask what you have in mind as to whether professional baseball should continue to operate.”

The President responded quickly, “I honestly feel that it would be best for the country to keep baseball going. There will be fewer people unemployed and everybody will work longer hours and harder than ever before.

“And that means that they ought to have a chance for recreation and for taking their minds off their work even more than before."

“Baseball provides a recreation which does not last over two hours or two hours and a half, and which can be got for very little cost. And, incidentally, I hope that night games can be extended because it gives an opportunity to the day shift to see a game occasionally.”

Despite FDR’s green light, it wouldn’t be business as usual for club owners and players. The war impacted just about every facet of American life and the National Pastime was no exception.

During the war, the government created the Office of Defense Transportation to exercise control over the railroads and make sure that national transportation priorities were met. While baseball might boost morale, Spring Training for ballplayers in Florida was by no means a national transportation priority.

And so, in coordination with the ODT, Judge Landis issued a January 1943 mandate that teams must train close to home beginning immediately. His edict further stipulated that all spring training sites must be north of the Potomac and Ohio Rivers and east of the Mississippi River. (The St. Louis Cardinals were given special permission to train west of the Mississippi in their home state of Missouri.)[1]

ODT director Joseph Eastman applauded the move, releasing a statement that he was “greatly pleased by the action which the major leagues have taken today to reduce their travel requirements for the coming season.”[1]

The ruling sent the Senators scrambling to find new digs. They inspected facilities at Georgetown University and Catholic University in the District but eventually decided upon the University of Maryland after club officials were able to negotiate a deal with university president H.C. Byrd. During camp, players would be housed in fraternity houses and dorms. The team would have use of the school’s baseball field and indoor field house, Ritchie Coliseum.

Compared to Florida, the setting was a bit anti-climactic as the esteemed Washington Post sportswriter Shirley Povich observed: “The Nats eight-mile trek to spring training camp was very un-thrilling. The athletes assembled at Griffith Stadium in the morning, piled into cars, hit the back road to College Park, and 15 minutes later were being shown to their rooms on the University of Maryland campus.”[2]

Senators owner Clark Griffith couldn’t resist the opportunity to needle the press corps, “This ought to be down your alley. You lazy guys can come out to Griffith Stadium, climb a light tower and cover our training camp by telescope."[2]

Not surprisingly, camp was a little different than what the players had grown accustomed to in Florida. Because of the weather, many practices were held inside the Ritchie Coliseum and involved more basketball-playing than baseball drills.

The Nats also faced a rather unique wartime issue. The team’s expensive pitching machine was on the fritz and needed new rubber bands in order to function. Rubber, of course, was crucial to the war effort and severely rationed.

As Griffith explained, “The machine operates with a heavy band of natural rubber that when snapped gives the force to the ball and we’re having a time buying new rubber. It’s high on the priorities list. There’s no such item as a synthetic rubber substitute for what we need. It must be the best native rubber. I’m hoping the government will release 5 pounds of it for us.”[3]

Despite the challenges, the team was able to prepare for the season. The Senators finished the 1943 season with a record of 84-69, good for second place in the American League. Not too shabby, especially compared to the (many) dismal seasons that earned the team the mantra, “Washington: First in war, first in peace and last in the American League.”

The Senators returned to College Park in 1944 and 1945. But, with the war over, the team headed back south in 1946. No doubt the players relished their return to the warm Florida sun. (No offense, College Park.)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)