The Roads Not Traveled: D.C. Pushes Back Against Freeway Plans

During the morning commute on Metro, trains are packed. A lot of riders are commuters coming in from Maryland or Northern Virginia. The Metro wasn’t the initial plan; back in the 1950s, the plan was to set up a freeway system to make it easier for people in the suburbs to access D.C.

The motivation for this was the beginning of urban decay in D.C. due to suburban sprawl, a.k.a. “white flight.” At the time, a report by urban planners pointed out that “... shifts of middle and upper-income whites to the edge of the city and into the suburbs have not helped downtown’s business. The fear is that these trends will persist.”[1] Another issue was that these people still worked in D.C., and so did the actual residents of D.C. The resulting commuter/resident traffic combination turned D.C. streets into a tangled mess.

Urban planners proposed a three part solution:

- Improve the mass transit system so people would be encouraged to leave cars at home

- Build more parking areas in the city so people wouldn’t park on the streets

- Build freeways in order to move commuters off of local streets, and to allow suburban money easy access to D.C. retail stores[2]

The freeway proposal came at an advantageous time; Eisenhower’s Federal Highway Act was passed in 1956 and it stated the federal government would pay 90% of the costs to build state highways.[3] This proved irresistible to city planners, who pushed for building and expanding a freeway system over the refurbishing of the mass transit system.[4]

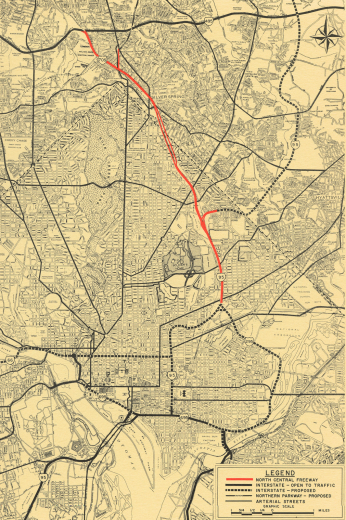

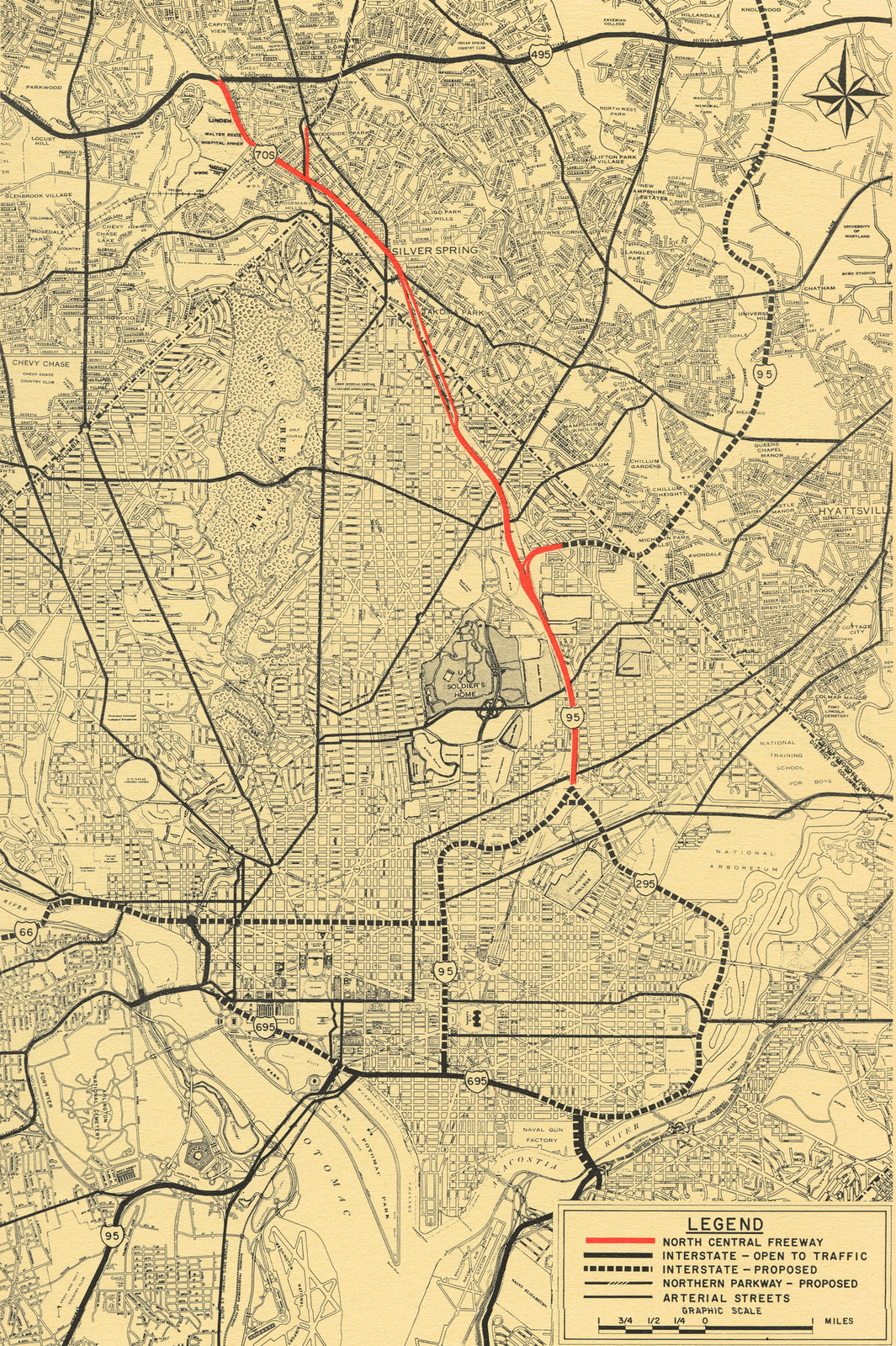

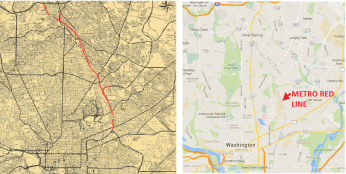

Early freeway plans were routed through upper Northwest D.C. but the rich white residents of the neighborhoods there refused the proposals.[5] Revised plans channeled the freeways through the poorer, blacker, Northeast neighborhoods. One of the most controversial sections of the freeway was the North-Central freeway, which city planning committees routed through Takoma Park in Maryland and on through Northeast D.C. This route had no less than 17 different versions,[6] each one as unappealing as the next. The number of homes that would be destroyed ranged from 1,300 to 3,000.[7] Some versions affected Takoma Park more heavily, some D.C. When the plans were made public, there was strong backlash. Protest groups formed, petitions were drawn up, and the fight was on.

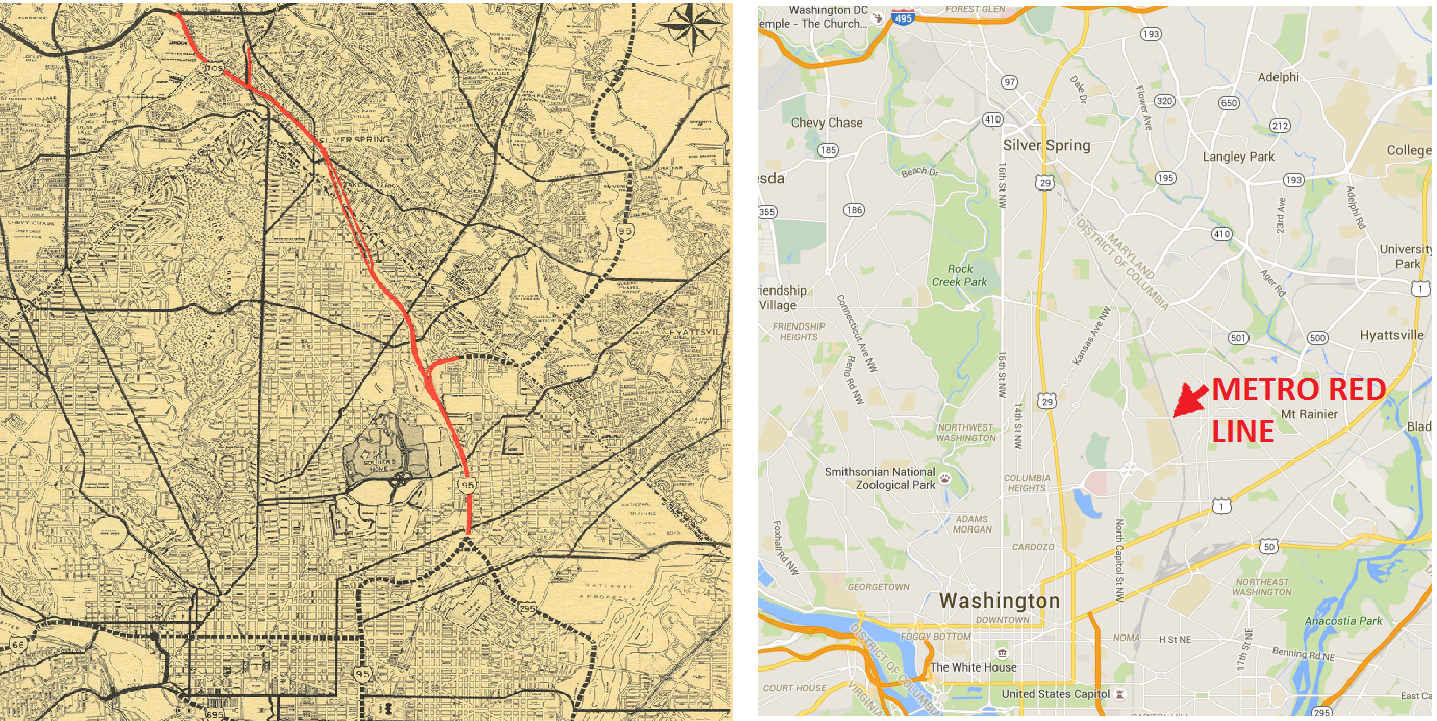

And what a fight it was. Verbal altercations and even physical altercations were the result of the interaction between the protesters and the planning committees.[8] During one hearing, Sammie A. Abbott, leader of the prominent citizen protest group, Emergency Committee on the Transportation Crisis (ECTC), suggested that the members of the planning committee should be put underground, along with the roads. The judge, sounding like a stern parent, told him, “Let’s act grown-up around here. That’s ridiculous.”[9] Another meeting dissolved into a brawl, ending with the arrest of Abbot and other members of the ECTC.[10]

Representatives for the freeway planning committees said that residents should simply accept the freeway, and that they would eventually get used to it running through the neighborhood. “Where do you live?” was the angry reply.[11] Protesters also pointed out that a majority of people displaced within the District were black. Robert Dunlavey, the vice chairman of an anti-freeway organization in Northeast, commented, “For Negro families ... displacement does not present simply the necessity to find a new house; it presents the prospect that an adequate house might not be available at all.” [12]

Protesters suggested that the freeway plans be tossed out and that a subway system take its place. “Subway yes, Freeway no” read a picket sign.[13] The general anti-freeway sentiment was that subways would achieve the same goal of moving people, and the construction would be a lot less destructive than building a freeway.

The idea of having a subway in D.C. was nothing new. As far back as 1944, consultants said that “a system of street car subways” would be the easiest transportation system to implement in D.C., not freeways.[14] City planners chose to pour their energies into the freeway system because the cost was to be offset by the federal government. Due to the pressure of the anti-freeway movement, though, city planners found themselves confronted with the reality of building a subway system. However, it would only complement the freeway, not stand alone.

But this wasn’t enough for irate protesters, who wanted complete removal of freeways. The battle moved to the courtroom when a group of citizens made up of lawyers formed The Committee of 100 on the Federal City.[15] The group, led by lawyer Peter Stebbins Craig, challenged the building of all freeways in D.C. under a law from the 1880s that said no highway in the city could be wider than Pennsylvania Ave, a law which all of the freeways planned for D.C. violated.[16] The Committee of 100 won in 1968, and the highway planning committee was less than thrilled. "Mentioning [Craig’s] name at the Highway Department is like waving a red flag in front of a bull," one paper is reported to have said at the time.[17]

Finally, under immense pressure and growing public outrage, freeway plans were scrapped altogether, without any freeways having been built in D.C. Metro opened in 1976[18] and part of the red line now runs along almost the same route where the North-Central Freeway was planned.

Today it’s hard to imagine what D.C. would have been like if the freeway plans had succeeded. Luckily, that’s something that residents will only imagine, not experience, thanks to the perseverance of those in the anti-freeway movement.

Footnotes

- ^ Jack Eisen, “’Energy Center’ Urged to Rid Downtown of Decay,” The Washington Post, July 2, 1959. http://search.proquest.com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/docview/149120813/B44…;

- ^ Chalmers M. Roberts, “Parking Crisis Threatens to Blight Retail Area of Washington,” The Washington Post, January 31, 1952, http://search.proquest.com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/docview/152491957/B44…;

- ^ Richard F. Weingroff, “Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956: Creating the Interstate System,” Public Roads 60, no. 1 (1996). http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/publicroads/96summer/p96su10.cfm.

- ^ D.C. Public Library, Washingtonia Division, D.C. Community Archives, Collection 36, ECTC: Printed Matter, Robert Kennan, “A Brief History of the Freeway Crisis,” June 12, 1967.

- ^ Kirsten Ronald, “Grad Research: Histories and Highways in Washington, DC,” AmStudies (blog), January 17, 2012, https://amstudies.wordpress.com/2012/01/17/grad-research-histories-and-….

- ^ “Takoma: Northern Central Gateway to Washington, D.C.” Highways and Communities, accessed November 30, 2015, http://web.archive.org/web/20061113053921/http://www.highwaysandcommuni….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Jack Eisen and Ina Moore, “Fists Fly at Voting on Roads: Bridge Foes Erupt as City Bows to Hill…,” The Washington Post, August 10 1969, http://search.proquest.com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/docview/147632857/339….

- ^ Jack Eisen, “Freeway Foes Confront NCPC,” The Washington Post, October 11, 1968, http://search.proquest.com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/docview/143334582/351….

- ^ Jack Eisen and Ina Moore, “Fists Fly at Voting on Roads.”

- ^ Paul A. Schuette, “Freeway is Again Attacked By Citizens and Businesses,” The Washington Post, February 5 1965, http://search.proquest.com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/docview/142491857/351….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ D.C. Public Library, Washingtonia Division, D.C. Community Archives, Collection 36, ECTC: Printed Matter, Robert Kennan, “A Brief History of the Freeway Crisis,” June 12, 1967.

- ^ Boby Levey and Jane Freundel Levey, “End of the Roads,” The Washington Post Magazine, November 26, 2000, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/metro/endofroads.pdf, 9.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Patricia Sullivan, “Peter Craig, lawyer in D.C. highway battles, dies at 81,” washingtonpost.com, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/12/20/AR20091….

- ^ “Metro History,” wmata.com, accessed November 30, 2015, http://www.wmata.com/about_metro/docs/history.pdf.

![Ben's Chili Bowl, 1980 (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Highsmith, Carol M, photographer. Ben's Chili Bowl, Washington, D.C. United States Washington D.C, None. [Between 1980 and 2006] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2011635251/. (Accessed December 04, 2017.) Ben's Chili Bowl, 1980 (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Highsmith, Carol M, photographer. Ben's Chili Bowl, Washington, D.C. United States Washington D.C, None. [Between 1980 and 2006] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2011635251/. (Accessed December 04, 2017.)](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/17058v.jpg?itok=egZM-IR9)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)