Before Pokemon Go There Was Mah Jongg

Having once acquired the taste for playing, a frenzy creeps over one and you seek opportunities for playing the game like a thirsty man…. Time means nothing…. midnight passes by unnoticed.[1]

The symptoms sound familiar. But, nearly 100 years before anyone dreamed up Pokemon Go – or smartphones for that matter – another craze was taking D.C. by storm:

"Mah-jongg has come to Washington. And never did a brilliant debutante, nor even royalty itself, so completely captivate and engross society men and women as mah-jongg is doing. Mah-jongg is not a man, neither a woman or a debutante. It is just the centuries old royal game of China."[2]

The “old royal game” (which is also called the “game of one hundred intelligences”) is played by two, three, or four players with a set of ivory or bone tiles depicting Chinese characters and symbols. The players start the game by building up a “wall” of tiles that are placed face-down in front of them. Then, they take turns drawing tiles from the wall. Through the process of drawing and discarding tiles, they seek to complete a legal hand, which is comprised of several particular combinations of specific tiles (called “melds”). Upon completing a hand, a player calls out “Mah Jongg!” and each player’s tiles are scored through a somewhat elaborate process that considers what melds or other tiles the player holds, how the (winning) hand was completed, whether the player possesses various special combinations of tiles, etc. The process is repeated for 16 hands.

Got it? If not, that’s okay. There is a lot to unpack. But, the good news is that there is a website devoted to teaching the game so you can brush up.

To some Mah Jongg – or Pung Chow as it was also known – was an easy game to grasp. To others, it was about as “easy as Einstein theory.”[3] But, what was undeniable is that it captivated high society when it reached Washington in the early 1920s.[4] As The Washington Post put it in 1923, "Washington has gone mah jongg or pung chow mad." People were playing constantly.

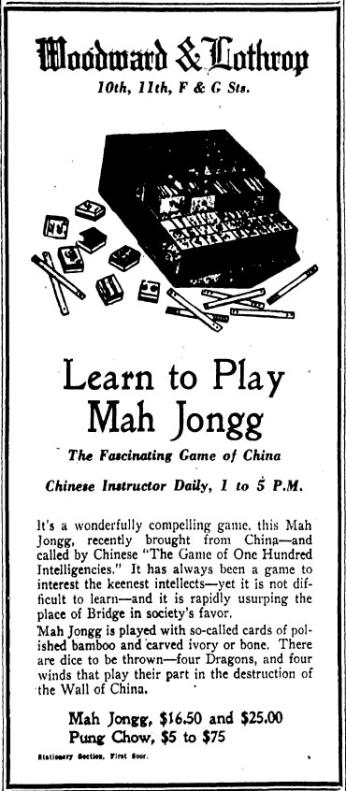

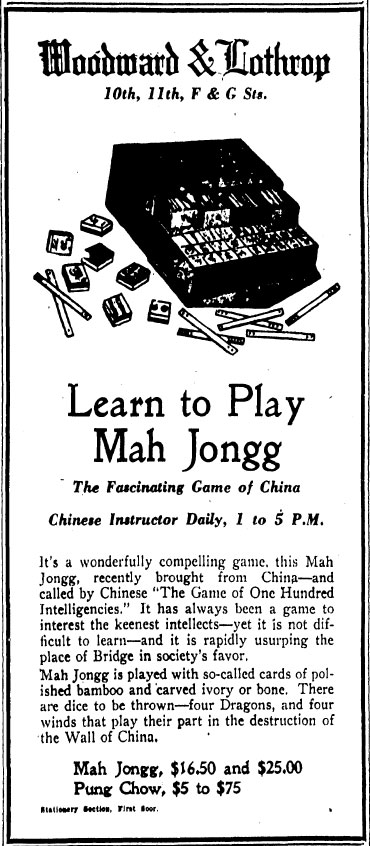

Reflecting the city’s appetite, the newspaper ran a nine-part series about the game in its Sunday edition during the spring of 1923, in which columnist Norman Jeffries explained strategies in impressive detail. Area department stores like Woodward & Lothrop and Lansburgh’s rushed to stock Mah Jongg sets on their shelves and made sure eager players could also pick up a box of Mah Jongg candy to serve at their next game party. Woodies even went so far as to hire a Chinese instructor to teach the game from 1-5 p.m. each day in its flagship store on F Street, NW.[5]

Part of the appeal was the supposedly exclusive, exotic history of the game, which one writer suggested “transports one from every-day affairs into the strange East, with its mystery and traditions of centuries.”[6]

Indeed, one popular tradition held that Mah Jongg was devised for the entertainment of royalty in China in the age of Confucius. Supposedly, the game was off limits for anyone outside the royal or mandarin classes, and those who were discovered playing were killed.[7] In actuality, however, the game was probably a 19th century invention. Still, it captivated westerners who visited China and exploded in popularity across the U.S. and Europe in the early 1920s.

In Washington, players included President and Mrs. Harding, along with several cabinet members and their wives.[8] Given the President’s proclivity for gambling, it’s no wonder that he took to Mah Jongg. As columnist E. Ellicott, Esq. put it, the game was “one of the neatest means of losing real money in the world,” but added, “If you have a winning streak and the game lasts seven or eight hours you have the new Rolls Royce in your garage for which you have been longing.”[9] This was the roaring 20s after all.

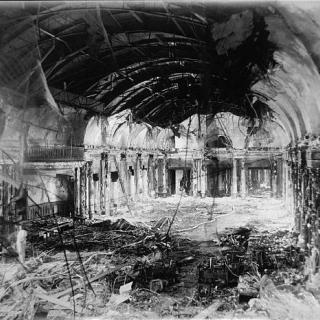

Perhaps the biggest testament to Mah Jongg's extraordinary popularity came in 1925 when some of Washington’s movers and shakers created a stage production based on the game and performed it at the then-new Washington Auditorium on 19th St. NW. [10] The “A Game of Mah Jong” show was a benefit for the Belleau Wood Memorial and featured scores of society girls dressed as human tiles. It was a “unique, colorful and picturesque” success according to the press, and attendees included several members of the Cabinet and the French Ambassador.

As it turned out, though, the show might have been the high water mark for Mah Jongg in Washington. The game’s popularity soon waned and, before too long, the fad had passed – replaced by crossword puzzles and other amusements – as newspaper cartoons joked about what former “addicts” should do with their now dusty Mah Jongg sets.[11]

Footnotes

- ^ Ellicott, E., "Ancient Game of Confucius Now Confuses Us," The Washington Post, 29 July 1923: 63.

- ^ “Centuries-Old Royal Game of China Luring to Many,” The Washington Post, 3 Dec 1922: 8.

- ^ Montague, James J., “Mah Jong As Easy As Einstein Theory,” The Washington Post, 25 Nov 1925: 62.

- ^ Mah Jongg was gaining enormous attention and popularity across the country in the early 1920s, so it is difficult to say for certain who introduced the game to Washington, though several sources credit Mrs. George T. Marye, wife of the former U.S. Ambassador to Russia, and Mrs. Gibson Fahnestock. See Ellicott, E., "Ancient Game of Confucius Now Confuses Us" and "Centuries-Old Royal Game of China Luring to Many, The Sunday Star [Washington, D.C.], 3 Dec 1922: 8.

- ^ See ad in The Evening Star [Washington, D.C.], April 7, 1923: 8.

- ^ Ellicott, E., "Ancient Game of Confucius Now Confuses Us."

- ^ “Learn Secrets of Pung-Chow Most Fascinating of Games,” The Washington Post, 20 May 1923: 33.

- ^ Ellicott, E., "Ancient Game of Confucius Now Confuses Us."

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Mah Jong Game Fantasy Presented in Auditorium,” The Washington Post, 7 Feb 1925: 5.

- ^ Lardner, Ring, “Disposal of Ancient Mah Jongg Sets Leads to New Foreign Trade Proposal,” The Evening Star, 26 April 1925: 5.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)