Marathon Mania Comes to D.C.

The 1908 Olympic Games had many firsts. It was the year when Americans allegedly refused to dip their flag at the opening ceremony, sparking a tradition that continues to this day, as well as the year John Taylor became the first African American to win a gold medal.

In the most controversial moment of the games, American Johnny Hayes was declared the winner of the marathon after Italian Dorando Pietri was disqualified for receiving illegal aid from officials.[1] A few months later, Pietri and Hayes held a rematch at Madison Square Garden where Pietri beat Hayes in front of over 10,000 spectators.[2]

The story launched a nationwide interest in long-distance running, dubbed “marathon mania.”

Marathons in the early 20th century were a far cry from the races we know today. The 1908 Olympic marathon length of 26 miles, 385 yards became the standard length for marathons, but during the marathon craze, any “long distance race” of three to fifteen miles was considered a marathon.

Many were less than impressed with the new sporting fad. “The Marathon craze is the expression of a national symptom,” one letter to the editor of The Washington Post wrote. The author predicted everything from Marathon hair curlers to Marathon pickles would “multiply in the market like a cloud of locusts on a Kansas wheat field” before the public lost interest.[3] For those who preferred not to run, there would soon be Marathon waltzing, Marathon ditch-digging, and Marathon novel-writing.[4]

But for every skeptic, there were many who saw the benefits of marathons. Johnny Hayes brought the marathon’s mythic origins to life in a manner that appealed to contemporary 20th-century men, eager to demonstrate their strength and virility. The prospect of American men literally outrunning their opponents suggested a bright future for the nation.[5]

Washington residents were soon eager to have their own marathon. “Let there be a service Marathon!” another letter to the editor declared. Navy and Marine Corps officers would run a short course along Pennsylvania Avenue from the Capitol to the Treasury. They would also participate in wrestling, javelin throwing, and parachute jumps from the Washington Monument.[6] A bright idea, but it never got off the ground.

By 1909, marathon mania was in full swing in DC. After a four-mile marathon with eleven competitors drew over 1,000 spectators in April, the Washington Post decided to sponsor a 15-mile race on May 29.[7]

The Post heavily promoted the race in the weeks leading up to the big day. It promised that famous marathoners such as Boston Marathon-winner Sammy Mullor would be in attendance and profiled local athletes. Teams representing Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Richmond also signed up to compete against local athletes.[8]

As entries poured in, the Post gave first-time runners a few training tips, including wearing light shoes and cutting smoking.[9]

Give up pastry, for it, in the language of the track, ‘cuts your wind.’ Walk often and long. This will help your leg muscles. You should get to bed at seasonable hours and rise at seasonable hours. Regularity of life will do much for you. There is no reason why the average young man in good condition and living a regular life should not be fit for this distance. It alone is not for speed; remember that. Endurance will tell.[10]

Gentleman reportedly practiced by running in Rock Creek Park with their attendants.[11] Over a dozen youth practiced on the grounds of the Soldiers’ Home.[12]

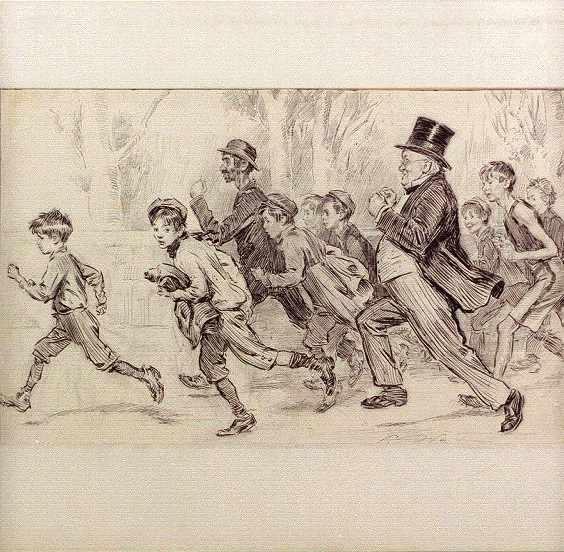

On the big day, 106 men took to the starting line. While today’s road races cater to male and female runners alike, the 1909 race was a male-only affair. Mothers and daughters stood on the sidelines. Worried grandmothers even began to pray.

While athletes had the sense to wear sleeveless jerseys and shorts similar to today’s joggers, the race didn’t begin until 2:30 pm – nearly the hottest part of the day. At least one runner was hospitalized after collapsing from exhaustion.[13]

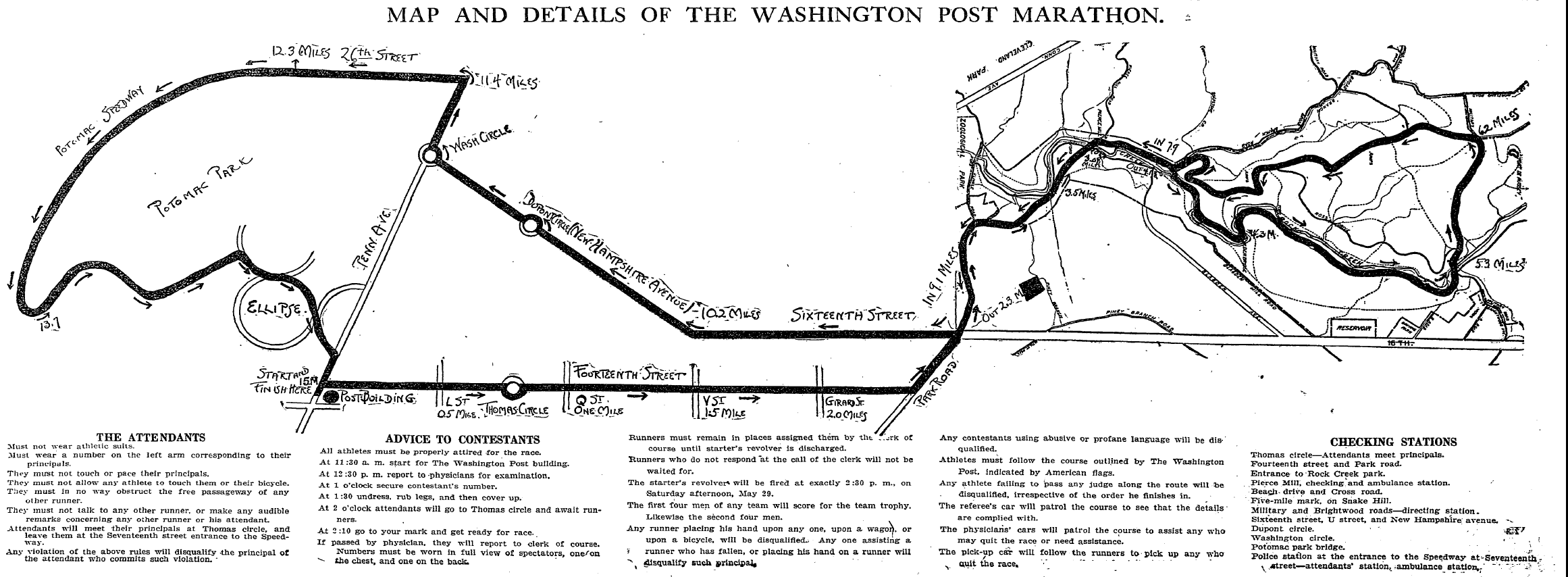

The racecourse began at The Washington Post building at 1335 E Street N.W. Runners headed north along 14th Street, made a loop through Rock Creek Park, ran back down 16th Street, turned onto Pennsylvania Ave., then looped around Potomac Park and back to the starting line. While roads were not closed, official cars helped to safeguard competitors from oncoming traffic. In honor of Memorial Day, the course was marked with American flags.[14]

The ruckus of the crowds led to a few near mishaps in the race. Runners on the sidewalk had to dodge dogs and baby carriages. While many well-to-do Washingtonians parked their cars on the grassy slopes overlooking the course, police struggled to keep crowds behind the established lines. By the time the runners entered Rock Creek Park, their motor escort had grown to over 100 cars, carriages, and bicycles which congested the race track.[15]

After the opening shot, a group of five runners quickly broke apart from the pack. At 14th and F streets, 21-year-old Charles Muller of the Mohawk Athletic Club of New York took the lead and set a rapid pace, while teammates Joseph Gilbert and Tommy Dwyer trailed close behind. By mile nine, Muller had a commanding lead. According to reports, he frequently asked how much further he had to go, and his friends always told him two miles less than the actual distance.[16]

In the last stretch, Muller was covered in sweat but held a 600 yard lead over his nearest competitors. He finished in first place with a time of 1:35:42, or 6:22.80 per mile. The top native son was J. G. Stecker of the Washington Y.M.C.A., with a time of 1:41:32.[17]

The first four runners received gold medals, while all 47 who finished the race received bronze. But for Muller, the biggest prize was a plate of ice cream. The race doctor warned Muller’s attendant, “I wouldn’t give him that if I were you. It is the worst possible thing he could take.”[18] So the attendant waited until the doctor’s back was turned to give Muller his treat.

According to final tallies, over 50,000 people watched The Washington Post marathon. “Nothing that has happened hereabouts in several years, with the single exception of the formal induction into the office of President Taft, has aroused so much popular interest,” said the Post.[19] Marathon mania hit DC in 1909 and hasn’t let up since.

Footnotes

- ^ Roger Robinson, “London’s Olympics: 1908 & 1948” Runner’s World, accessed August 5, 2016, http://www.runnersworld.com/races/londons-olympics-1908-1948.

- ^ “Dorando Beats Hayes,” The Washington Post, November 26, 1908.

- ^ “The Marathon Craze,” The Washington Post, December 29, 1908.

- ^ Wallace Irwin, “Exercise,” Evening Star, May 09, 1909.

- ^ “Marathon Running,” The Washington Post, May 30, 1909.

- ^ “A Service Marathon,” The Washington Post, January 06, 1909.

- ^ “Crack Distance Runners to Compete in the Post’s Marathon Race,” The Washington Post, May 05, 1909.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Many Applications Being Made for Marathon Entry Blanks,” The Washington Post, May 09, 1909.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Big Field is Promised for the Post Marathon Race,” The Washington Post, May 10, 1909.

- ^ “Sam Mellor to Compete in Post’s Marathon Race,” The Washington Post, May 11, 1909.

- ^ "Muller Wins the Post Fifteen Mile Marathon,” The Washington Post, May 30, 1909.

- ^ “One Hundred Crack Runners to Toe Scratch in Post’s Marathon,” The Washington Post, May 29, 1909.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Muller Wins the Post Fifteen Mile Marathon.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)