Long Before Prohibition, D.C. Had a Brief Ban on Liquor

The day before Prohibition took effect in the District of Columbia, bars in Washington were rushing to fill their orders. There were “seventeen hours of feverish hustle in acquiring liquors for immediate and future consumption,” according to the Washington Post.[1]

But this likely wasn’t the first such scene in the District. On Aug. 14, 1832, 85 years before D.C.’s 16-year ban on alcohol began, D.C. had another short-lived ban on liquor sales.

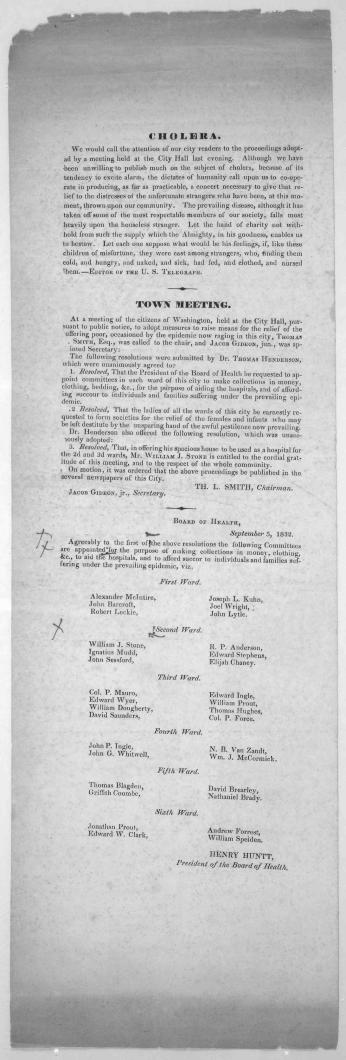

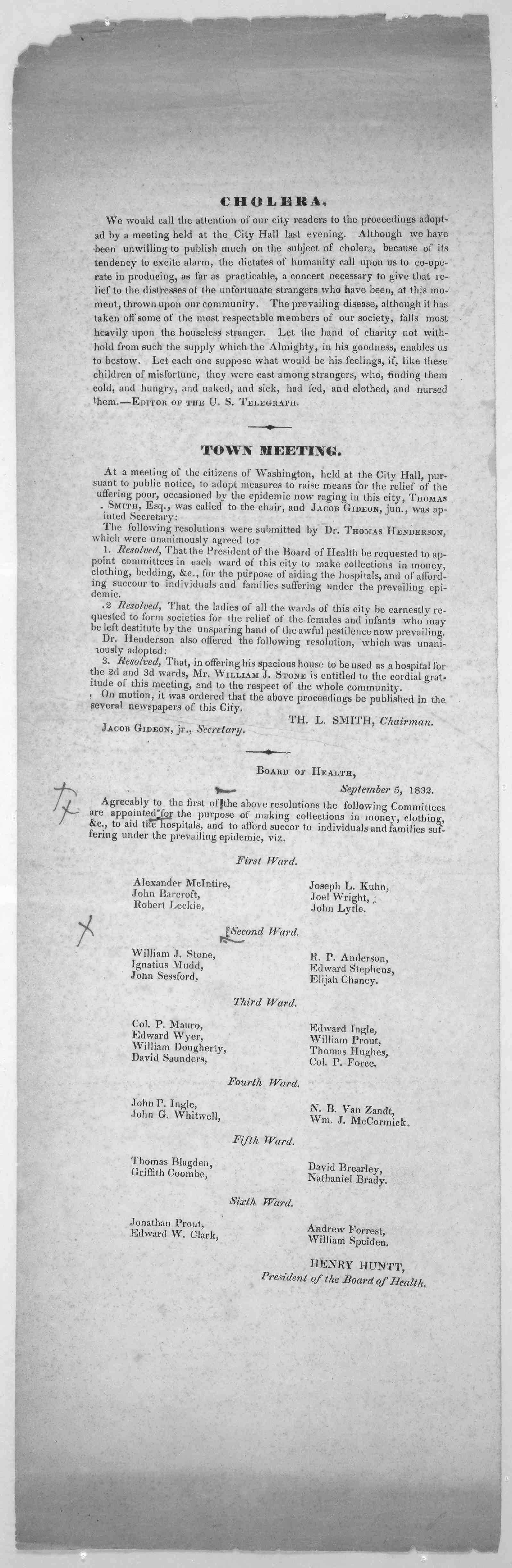

The ban, ordered by the D.C. Board of Health, came as a cholera epidemic threatened people across the city and in cities throughout the eastern and Midwestern United States. Issues of the National Intelligencer filled with brief obituaries for victims of the disease. By the order of municipal boards of health, papers published lengthy reports of people like John Nally, a D.C. printer who had diarrhea for three weeks before dying at the hands of his doctor.[2]

Thanks to research performed later in the 19th century, we now understand that cholera comes from bacteria, which thrives in unsanitary conditions that were common in 19th century cities. In this era before Washington had a modern sewer system, water could be contaminated by feces. But 1832 was both before British physician John Snow mapped cholera cases to a local water supply and before germ theory transformed the field of medicine.[3] Instead of wells, doctors pointed the blame toward the evils they knew, which ironically included one of the things that could have helped: alcohol.[4]

Frequently, the reports in the papers of cholera deaths mentioned that the victim was alcoholic. Nally was “an unfortunate young man” who “had been a habitual drunkard for the last four years, and for six weeks previous to his death, had indulged in all manner of excess, having been scarcely sober in the time.” Other accounts merely stated that those who died were “intemperate.”[5]

The message was clear: for whatever reason, cholera and alcohol didn’t mix.

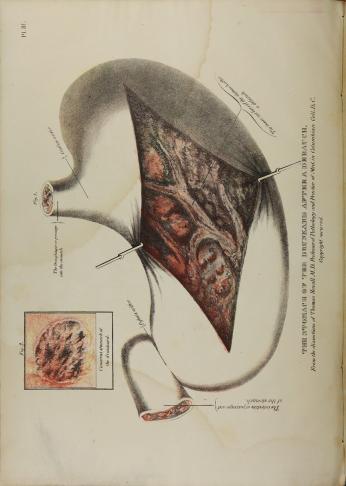

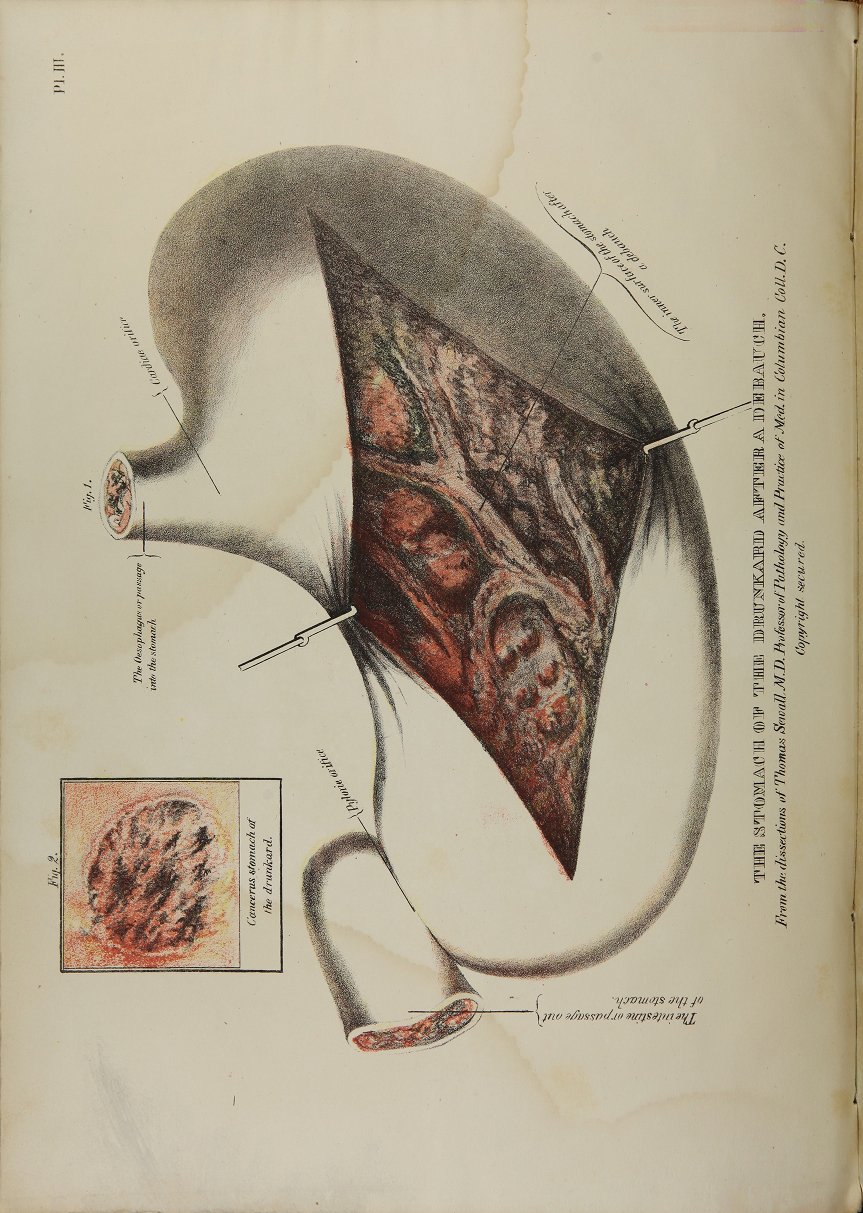

For early temperance advocates, this was a form of vindication, proof of the evils of strong alcohols and heavy drinking. According to the American Temperance Society, nine-tenths of the people who died of cholera were heavy drinkers.[6] Thomas Sewall—a member of the D.C. Chapter of the American Temperance Society, a doctor to three American presidents, and a member of the D.C. Board of Health—stated later that cholera “wherever it appeared, singled out the intemperate for its victims, in a marked and most extraordinary manner.”[7]

Cholera provided them with the evidence that alcohol was, as Sewall had put it in 1830, “a vice…attended with so many circumstances of suffering, mortification, and disgrace, that it seems difficult to understand how it should ever have become a prevalent evil among mankind.”[8]

Other medical professionals took a wider view. According to Henry Hunt, the Director of the D.C. Board of Health, “whatever disorders the stomach and bowels, predisposes to Cholera.” Under this description, beer, cider, and acid wines were bad for one’s health. So, too, were unripe and watery fruits, as well as shellfish.[9]

According to this thinking, certain alcohols—ones that did not upset the stomach—were fine to drink. Madeira wine, Hunt wrote, was a good choice of beverage during the epidemic. Sherry and brandy were acceptable to drink in moderation.[10]

But one thing was clear: the Board of Health felt it needed to do something to prevent people from drinking heavily and from drinking stronger alcohols.

The Board took the first step toward doing this in late July 1832. One action in a series of resolutions that the Board passed unanimously urged that the City Council enact a law that “will effectively close all the dram shops, or drinking houses, throughout the city, and to restrain as much as possible, intemperate drinking.”[11]

But closing the bars didn’t really solve the problem. As long as people could buy alcohol, they could easily consume strong drinks at home. So, on August 14, the Board took their next step: They voted that the sale of so-called “ardent spirits,” or distilled drinks, “in whatever quantity…is hereby directed to be discontinued for the space of ninety days from this date.”[12]

Washington, D.C. was not the only city to enact such a ban. Cleveland, Ohio, and Haverhill, Massachusetts did as well.[13]

The ban on “ardent spirits” or on drinking houses was not the only form of prohibition the Board of Health took to prevent the spread of cholera. On Aug. 16, the Board banned all theatrical shows and several foods, such as melons and shellfish, for 90 days.[14]

But the ban on ardent spirits seems to have gone further than a simple health precaution and into an act of early temperance regulation. In obituaries, only the drinking habits of the dead were mentioned; their diets were not. And the new law banned people from selling brandy, despite the fact that Hunt had previously called that drink fine in moderation. Meanwhile, the Board didn’t ban any other food that Hunt had previously deemed acceptable.

The Board’s decision fit into the thinking of the early Temperance Movement, which had no objections to drinking wine, beer, or cider in moderation.[15] It was an early example of the regulation of alcohol.

Eighty-five years later, once the Temperance Movement turned to arguing that all drinking, even in moderation, was immoral, the District’s bars and drinking residents rushed again to grab their last drinks.

Footnotes

- ^ “D.C. Dry at Midnight,” Washington Post, October 31, 1917, ProQuest.

- ^ Alex M.D. Davis to Henry Hunt, 14 August 1832, Volume 1, D.C. Board of Health Minutes 1822-1878, District of Columbia Archives, D.C. Office of Public Records and Archives.

- ^ Charles Rosenberg, The Cholera Years: The United States in 1832, 1849, and 1866 (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1987), 193.

- ^ In a 2011 study published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, microbiologists Janet Guthrie and Darrel Ho-Yen found that cholera did not survive for a long time in just about any concentration of alcohol. Janet S. Guthrie and Darrel O Ho-Yen, "Alcohol and Cholera," Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 104, no. 3 (2011): 98, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3046197/.

- ^ D.C. Board of Health, 14 August 1832, Volume 1, D.C. Board of Health Minutes 1822-1878, District of Columbia Archives, D.C. Office of Public Records and Archives.

- ^ American Temperance Society, Fifth Annual Report of the American Temperance Society (Boston: American Temperance Society, 1832), 8.

- ^ Thomas Sewall, The Pathology of Drunkenness, or the Effects of Alcoholic Drinks, with Drawings of the Drunkard’s Stomach (Albany: C. Van Benthuysen, 1841), 15.

- ^ Thomas Sewall, An Address Delivered Before the Washington City Temperance Society, November15, 1830 (Washington, D.C.: Washington City Temperance Society, 1830), 4.

- ^ Henry Hunt, 2 July 1832, Volume 1, D.C. Board of Health Minutes 1832-1878, District of Columbia Archives, D.C. Office of Public Records and Archives.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ D.C. Board of Health, 26 July 1832, Volume 1, D.C. Board of Health Minutes 1832-1878, District of Columbia Archives, D.C. Office of Public Records and Archives.

- ^ D.C. Board of Health, 14 August 1832, Volume 1, D.C. Board of Health Minutes 1832-1878, District of Columbia Archives, D.C. Office of Public Records and Archives.

- ^ Rosenberg, The Cholera Years, 97.

- ^ D.C. Board of Health, 16 August 1832, Volume 1, D.C. Board of Health Minutes 1832-1878, District of Columbia Archives, D.C. Office of Public Records and Archives.

- ^ Mark E. Lender and James K. Martin, Drinking in America: A History (New York: The Free Press, 1987), 68.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)