A Fight to End Horse Racing and Gambling in Alexandria

The St. Asaph racetrack in Alexandria was beautiful. According to the Alexandria Gazette, “the track is certainly a fine one, the buildings are handsome and commodious and many more are to be erected—all with an eye to architectural beauty.” People in the grandstand had a constant view of the stables and of the “verdure clad hills, which stretch far away” in the background.[1]

But that was only the surface. Behind the scenes was a constant scourge of scandal. People allegedly put lead shoes on fast horses in order to slow them down.[2] One horse, someone claimed, was poisoned just before a race.[3]

The cause of the misconduct lay in a barn a quarter-mile away from the track. In that building, there was a constant flurry of gambling activity. People placed bets on the St. Asaph races, with the owners of some of the horses placing bets against their own horses.[4] Other patrons bet on more prominent races in New Orleans and St. Louis, hearing the results from Western Union’s telegraph service.[5] Still, others played poker, keno, and faro.[6] As The Washington Post put it, “It was one mass of humanity playing the races in a fashion that made the hearts of the bookmakers glad.”[7]

But at the turn of the 20th century, when prohibitions on gambling were being enacted across the country, this poolroom was sure to be met by broad pushback. Indeed, before it even opened, St. Asaph was under attack. In 1893, one year before the opening, the Virginia Assembly banned gambling in the state. But lobbyists carved out exemptions, including one that allowed gambling at “driving clubs” like the Gentlemen’s Driving Club at St. Asaph.[8]

From there, the threats only continued. In 1896, an anti-gambling measure called the Maupin law passed through the Virginia state legislature. Track owner John M. Hill fought to bring that law to the courts—at one point, the Post reported that St. Asaph’s owners were disappointed because they were not arrested under this law—challenging that it was unconstitutional.[9] The Supreme Court of Virginia decided that although the law was constitutional, it did not apply to St. Asaph.[10]

In 1897, the state of Virginia outlawed horse racing altogether.[11] This affected business at St. Asaph directly, but the proprietors found other ways of making up the money. During the Spanish-American War in 1898, for instance, the track was lent to the U.S. Army as a mobilization camp.[12]

By 1900, Hill set up an absurdly elaborate venture in order to circumvent Virginia’s anti-gambling laws, which not only banned horse racing within the commonwealth but also prohibited people from forwarding money directly to race tracks for the purpose of gambling. To get around the edicts, Hill created a corporation called the West Virginia Athletic Association based across state lines in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia where horse racing and gambling were legal. He then chartered the Old Dominion Telegraph Company to indirectly conduct the business that had officially been placed through the WVAA.

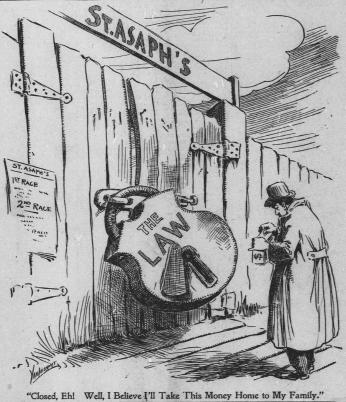

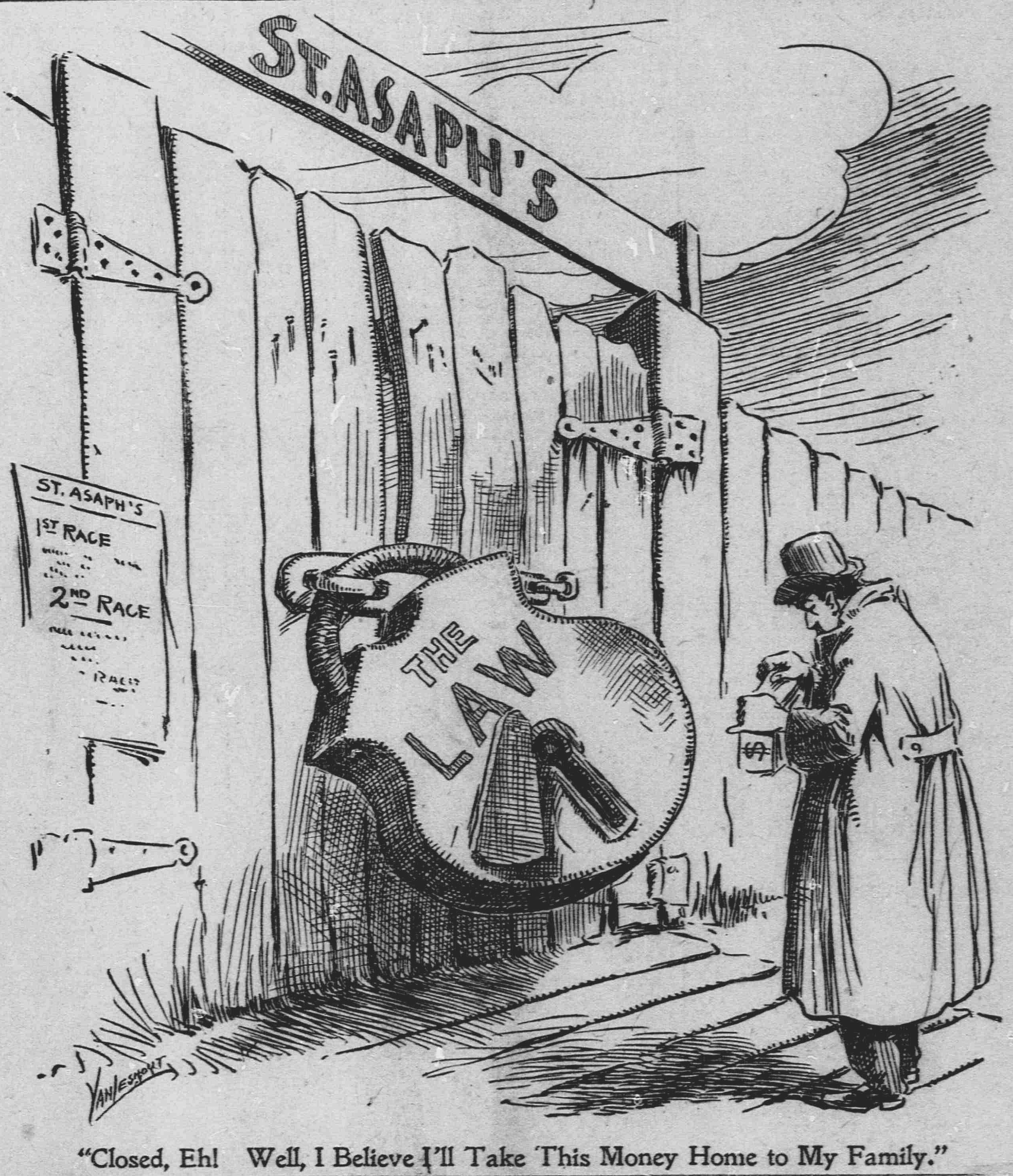

All of this meant that although horses hadn’t run at St. Asaph in several years, Hill’s track still ran a profitable gambling business—all apparently in compliance with the law.[13]

With this game of legal gymnastics, Hill kept St. Asaph alive. That is, until an unrelenting prosecutor singled out the track.

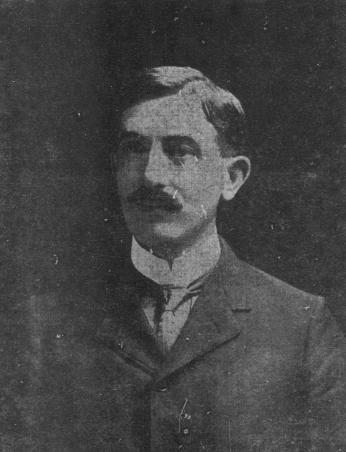

Born in Louisiana, Crandal Mackey was determined to see an end to widespread gambling and corruption in Alexandria. In 1903, he became attorney for the Commonwealth of Virginia, promising to “close up every gambling resort in Alexandria county if there was law enough in Virginia to enable him to do so.”[14]

But Mackey’s quest wouldn’t be easy. Hill had an impressive legal team working behind him. And, with an alleged $12,000 per year in the St. Asaph budget allocated for corruption, there were plenty of forces eager to help Hill out.[15]

The sheriff of Alexandria County, for instance, opposed anti-gambling measures and was accused of tipping off gambling sites before he raided them.[16] The courts, too, resisted Mackey’s efforts. In 1904, Mackey tried to have four people, including Hill, convicted on gambling-related charges, but he dropped their cases upon learning that the cases would be heard by justices who were known to be sympathetic to the track.[17] Even the Alexandria Gazette might have been in on the game: According to Mackey biographer Michael Lee Pope, the paper rarely covered Mackey’s efforts to shut St. Asaph down, something Pope suspects might have been because the racetrack bribed the newspaper.[18]

Meanwhile, St. Asaph’s legal team was incredibly adept. The track’s lawyers tried to drag out the case in an attempt to get Mackey to drop it. At one point in the trial, astute lawyers for Hill noticed that Mackey had charged “James M. Hill,” and not “John Marriot Hill,” for gambling crimes and asked the judge to dismiss the case. The judge delayed, but didn’t dismiss, it.[19]

But Mackey wasn’t going to give up his fight. “I burned my bridges behind me when I took up this fight, and I am going to push it for all I am worth,” he said.[20]

Eventually, Mackey found his opening. In trying to rid themselves of the attorney’s pressure, Hill made a huge blunder.

Hill and his brother schemed with Alexandria mayor Frederick Paff to stage a fake raid at the racetrack. Presumably, they hoped that the raid would make it look as if St. Asaph wasn’t simply a casino operating in legal gray areas. Or perhaps they hoped the raid would stop people from investigating corruption and bribery charges.

Whatever the case, the plan backfired. For whatever reason, Hill only wanted the raid to occur if he was present. But his trolley to the track was delayed, so he called the mayor to cancel it.[21]

Only he didn’t call the mayor. In yet another tough break for Hill, the call got routed to the Alexandria County Courthouse—and straight to Crandal Mackey. In short time, the Alexandria Police Department conducted an actual raid on St. Asaph and arrested 33 people. That move predictably did not please Alexandria’s corrupt mayor, who said, “I do not know who ordered the raid on St. Asaph, but I maintain that no one had a right to order it except myself.”[22]

By the end of the ordeal, Mackey wasn’t hoping to send John Marriot Hill or any of the other proprietors at St. Asaph to jail. He just wanted to see St. Asaph shut down.

In January 1905, Mackey got his wish. Hill and his brothers promised to move out of Alexandria County. In exchange, Mackey agreed to not prosecute them.[23]

In the following years, the grounds at St. Asaph found many uses. Homeless African Americans lived in the grandstands and judge’s tower in 1914. During World War I, the Army once again used the space as a mobilization camp. But the poolroom that had made St. Asaph infamous—that was forever gone.

Footnotes

- ^ Michael Lee Pope, Shotgun Justice: One Prosecutor’s Crusade Against Crime and Corruption in Alexandria & Arlington (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2012), 60.

- ^ Ibid., 64.

- ^ “Accused of Poisoning Beatrice,” The Washington Post 30 December 1895.

- ^ “Racing May Conflict,” The Washington Post 12 August 1895.

- ^ “Odds on Other Races,” The Washington Post 20 March 1894.

- ^ “St. Asaph Racetrack,” City of Alexandria Historical Marker.

- ^ “Odds on Other Races,” The Washington Post.

- ^ Pope, Shotgun Justice, 59.

- ^ “Pool Sellers Unmolested: St. Asaph People Disappointed at Not Being Arrested,” The Washington Post 24 March 1896.

- ^ “Maupin Law Verdict,” Washington Post 30 April 1896.

- ^ Pope, Shotgun Justice, 57.

- ^ “Army Supply Trains,” The Washington Post 26 September 1898.

- ^ Pope, Shotgun Justice, 63.

- ^ “Crandal Mackey and His Fight for Law in Alexandria County,” The Washington Times 22 May 1904.

- ^ Notably, Crandal Mackey was the one making the claim. “Policy War Is Now On,” The Washington Post 17 April 1904.

- ^ Pope, Wicked Northern Virginia (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2014), 119.

- ^ “Poolroom Men Won,” The Washington Post 18 September 1904.

- ^ Derrick Perkins, “Author Documents Life and Times of Gun-Toting Prosecutor,” The Alexandria Times 22 November 2012.

- ^ Pope, 78.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Shotgun Justice, 83.

- ^ Pope, 83; “St. Asaph is Raided,” The Washington Post 10 January 1905.

- ^ “Poolroom at St. Asaph Promises to Move Away,” The Washington Times 11 January 1905.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)