John Layton, the M.P.D., and the 1968 Washington Riots

Washington, D.C. became a focal point for African Americans migrating from the segregated south before and after World War II. The Supreme Court’s decisions calling for desegregation of the city’s schools and public institutions in Bolling v. Sharpe and District of Columbia v. John R Thompson Co. in 1954 paved the way for greater racial diversity and opportunity.[1] Washington became the first major U.S. city with a majority black population in 1957, and President Lyndon Johnson appointed an African American mayor to the city in 1967.

Despite all these hallmarks at the height of the post-World War II civil rights struggle, racial tensions in Washington reached dangerous levels in the late 1960s. The growing suburban middle-class African American population proved a sign of economic progress, but this progress was far outweighed by the plight of blacks in the inner city.

“The poor young Negro lives in physical segregation and psychological loneliness,” Attorney General Ramsey Clark told the Women’s Forum on National Security in Washington on February 20, 1968. “He is cut off from his chance. Fulfillment, the flower of freedom, is denied him. A small disadvantaged and segregated minority in mighty and prosperous nation, he is frustrated and angry.”[2]

Riots were becoming a more common occurrence in the inner cities during this period. In 1967, violent riots had already rocked cities such as Los Angeles, Detroit, and Newark. These violent incidents all had similar motivating factors—widespread poverty, lack of economic opportunity, and poor relations with law enforcement.[3]

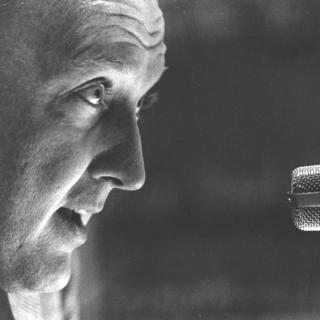

John Layton was a police officer who was sensitive to the issue and hoped to make a change. As D.C.’s Chief of Police, Layton took on the responsibility of managing not only the department’s role in protecting the community, but also in maintaining good relations with it as well.

Layton joined the police force in 1936, making lieutenant in 1945, then rising to Deputy Chief in 1963. He was promoted to chief in 1964, at a time when the police department had a good public reputation, but declining relations with the African American community.

Substandard housing, lack of access to adequate public facilities such as schools and hospitals, and lack of jobs led to deep feelings of frustration and helplessness among the African American community in Washington.

These sentiments were compounded by perceptions among the African American community that they were being singled out by police. Accusations of police brutality, racial profiling, and disproportionately harsh treatment in searches and arrests were rampant. By the late 1960s, an undercurrent of hostility existed between the D.C. Police Department and the African American community in Washington.

Layton added resources to the Community Relations Unit and promoted the first African American to the rank of Captain. He created a Public Information Division to better coordinate communications with the public and the media.[4] He was also on record as noting that the Washington D.C. police department would not rely on lethal force should they need to put down a riot. This was an open attempt to recognize the African American community’s complaints about police brutality and harassment.

Layton’s actions were put to the test on April 4, 1968. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, TN that day, and when word reached Washington, D.C., angry crowds began gathering in the streets.

Activist Stokely Carmichael took to the streets and demanded that local businesses close down out of respect for King. The crowds around him became more incensed, and at around 5 p.m., the first storefront window was broken near 14th Street, NW and U Street. It was an isolated act, but by 11 p.m. looting had begun.

On April 5, violence spread down 7th Street, NW and along the H Street corridor. Layton stuck to his promise and ordered the police to use tear gas rather than bullets to contain the rioters, but the D.C. police force was quickly overwhelmed. The National Guard was called out to protect the White House and other federal buildings.

The riot came to an end on April 8 and order was restored. Ten deaths were reported, over 7,600 people were arrested, and more than 1,200 fires were started. Damage based on insurance claims was pinned at $25 million, but this does not account for uninsured property that was destroyed or insurance policies that were cancelled. The loss of revenue due to reduced tourism in April and May was estimated at $40 million.[5]

Washington, D.C. was one of 100 cities that suffered rioting in the wake of the King assassination, but it witnessed a military occupation larger than any city since the Civil War. Layton received a great deal of criticism for the role of the police department in helping to incite tensions despite his actions to improve relations. He resigned as Chief in 1969.

Footnotes

- ^ See https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/347/497/case.html for details on the Bolling decision and https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/346/100 for details on the Thompson decision.

- ^ Ramsey Clark, Address to Women’s Forum on National Security, February 20, 1968, U.S. Department of Justice website, https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/ag/legacy/2011/08/23/02-20-…

- ^ The National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders study, released on February 19, 1968, detailed the causes of civil unrest. Excerpts can be found here: http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/6545/

- ^ See John Layton’s biography at the Metropolitan Police Department website: http://mpdc.dc.gov/biography/john-b-layton

- ^ “The Response of the Washington, D.C. Community and Its Criminal Justice System to the April 1968 Riot,” George Washington University Law Review, May 1969, p. 867.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)