To Duck the Scold: One of Anne Royall's Washington Incidents

When Anne Newport Royall went to court in 1829 for being a “public nuisance, a common brawler and a common scold,” there were mixed feelings.[1] Some celebrated the news that she was finally getting what she deserved, like the Aurora & Pennsylvania Gazette, which said, “All decent people will be happy to hear that the imprudent virago, Anne Royall, is at last in a fair way to meet her deserts.”[2] (A virago, for reference, is a loud overbearing woman.[3] This wouldn’t be the last time she’d be chastised for unladylike behavior.) Others likened her trial to the persecution of Galileo by the Catholic Church, claiming that she will never surrender.[4]

The incident in question was when a fire engine house near her home on Capitol Hill was being used as a Presbyterian meeting place—a practice Royall objected to because the engine house had been built with federal money.[5] Royall strongly believed in separating the church and state, since she felt corruption emanated from both. Previously, she had earned the ire of Philadelphia's Rev. Ezra Stiles Ely who tried to form political alliances to create a more Christian government.[6] She blasted the Presbyterians, calling them “‘blue-skins,’ ‘blackcoats’ and ‘copper-heads’ as she detailed their political plots and thus earned herself a reputation as a vulgar, offensive woman… Ely and his followers considered Royall a devil and devised a plan to punish her.”[7]

But, before they could do so, Royall found herself embroiled in the controversy surrounding the Capitol Hill engine house. She claimed the children would throw rocks at her window, and that people, “blackcoats” that she had previously insulted, would pray beneath her window and try to convert her. According to her accusers, she responded to all of this with “sundry wicked sayings…and various outrages upon the peace and harmony of society.”[8] It, apparently, was “no wonder then that the inhabitants of Capitol Hill should rise en masse, and flock to the court to give testimony.”[9]

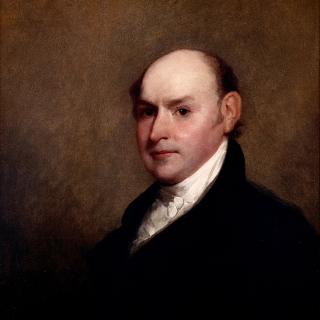

Under normal circumstances, this would have remained an amusing local incident. But Anne Newport Royall gained national attention because she had already made a name for herself, both in Washington and throughout the United States. She had first come to the nation’s capital to present her case to receive her widow’s pension for her husband who had died as a soldier in the Revolutionary war, and in the course of fighting for that, she had grown close to John Quincy Adams and his wife, Louisa.[10] (She was rumored to have been granted an interview with Adams by sitting on his clothes while he bathed in the Potomac.)[11] She had published several travel writings as she moved about the country, such as Sketches of History, Life and Manners in the United States and The Tennessean.[12]

No matter how she was received throughout the country, how she was received in court could mean the difference between a fine or a downright medieval form of punishment.

Royall was charged on June 1, 1829 with “being a public nuisance, a common brawler and a common scold,”[13] however, she was managed to have the first two charges quashed, so that she was only tried as a common scold.[14] She was the last to testify in her own trial and was described as “fidgety…but sufficiently restrained by the presence of the Court to avoid giving specimen of her usual line.”[15] By the end of her case, the Grand Jury found her, “being an evil-disposed person, and a common slanderer and disturber of the peace and happiness of her quiet and honest neighbors,” guilty of being a common scold.[16] From there, it was a matter of punishment:

“The punishment, also, is a perplexing subject, for the lawyers seem to have ransacked the Maryland code in vain to find some precedent, and among the negligences of Congress may be enumerated the omission to enact some benefitting penalty for the common scold.”[17]

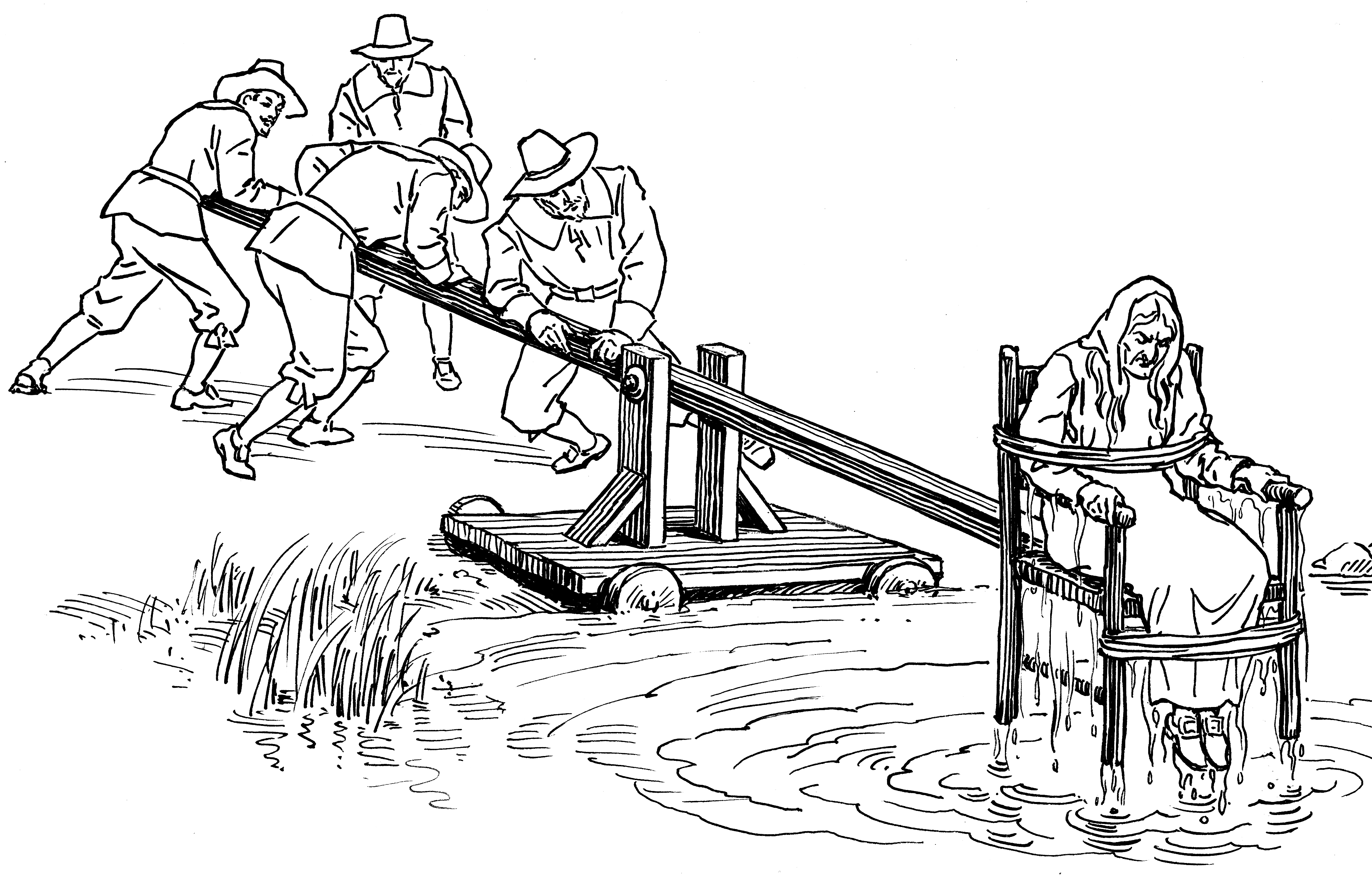

The court determined that the punishment for a scold was the “ducking stool.” The device was “a seat set at the end of two beams twelve or fifteen feet long that could be swung out from the bank of a pond or river,” and the scold would be submerged in the cold water.[18] Yet, Royall “smiled very graciously” when the opposing counsel “expressed his desire that she should enjoy a cold bath with as much privacy as possible.”[19] Meanwhile, Royall’s lawyer argued that the practice was out of touch, saying that an English Judge “was of the opinion that a ducking would only have the effect of hardening the offender.”[20] He noted that according to legal writers, once a scold receives that punishment, they receive impunity to scold “ever afterwards.” As the Daily National Intelligencer reported:

“He begged the court that they would weigh this matter, and not be the first to introduce the ducking-stool, which had been obsolete in England since the rule of Queen Anne, reminding them that the very introduction of such an engine of punishment might have the effect of increasing criminals of this class.”[21]

The ducking stool hadn’t been used in England since 1807.[22]

Royall was able to escape the cold bath, when the court declared “that she be fined ten dollars and costs, give security in the form of 250 dollars for her good behavior for one year, and stand committed to prison until the sentence be complied with.”[23] This would have been $250.52 and costs, and security in the form of $6,263.12 in today’s money.[24] Still, the fine was paid by two reporters from the Daily National Intelligencer,[25] and her security was paid by the second Auditor of the Treasury, the Postmaster of Washington, a clerk, and the Secretary of War.[26] The hefty security deposit was to guarantee her good behavior. If she resumed the scold-worthy actions, she would be put in jail and the money would be lost. Once that was done, she resumed her travels to escape further embarrassment.[27]

As it turned out, Royall stayed out of trouble with the law (as antiquated and gender biased as they were) during her probation. But this wouldn’t be her last time in Washington. She returned in 1831 and would go on to create two publications. First, Paul Pry and that was then replaced by The Huntress. Working with her friend Sally Stack, a typeface donated by the Daily National Intelligencer, and local orphans to deliver it, the paper exposed hypocrisy, nepotism, and laziness in the government.[28] The paper was “dedicated to exposing all and every species of political evil and religious fraud, without fear or affection.”[29]

Finally, in 1848, Congress passed a new pension law—Royall’s original reason for coming to Washington, D.C. She was able to finally receive the pension, however her husband’s family still claimed most of the money. Still, she couldn’t be deterred from publishing The Huntress for a few years more until she died in 1854 when she was 85.[30]

Royall is buried in the Congressional Cemetery, and her stone reveals the ultimate respect Royall gained. Beneath her title of “Pioneer Woman Publicist,” her stone notes it was “Erected in appreciative recognition by a few men from Philadelphia and Washington.”

Footnotes

- ^ Cynthia Earman, “An Uncommon Scold: Treasure-Talk Describes Life of Anne Royall,” Library of Congress, Jan. 2000, Accessed Mar. 2, 2017.

- ^ Aurora & Pennsylvania Gazette, Jun. 24, 1829.

- ^ “Definition of VIRAGO,” Merriam Webster, 2017, accessed March 2, 2017

- ^ [4] “Mrs. Royall in Trouble,” Carolina Observer, Jun. 25 1829

- ^ Earman, “An Uncommon Scold: Treasure-Talk Describes Life of Anne Royall.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Mrs. Royall,” Aurora & Pennsylvania Gazette, Jul. 22, 1829.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Earman, “An Uncommon Scold: Treasure-Talk Describes Life of Anne Royall.”

- ^ Jeff Biggers, “America’s First Blogger: Anne Royall,” The Huffington Post, Jun. 10, 2008. Accessed Mar. 21, 2017.

- ^ Earman, “An Uncommon Scold: Treasure-Talk Describes Life of Anne Royall.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Circuit Court of the United States,” Daily National Intelligencer, Jul. 20, 1829.

- ^ “Mrs. Royall,” The Indiana Journal, Aug. 13, 1829.

- ^ “Circuit Court of the United States.”

- ^ “Mrs. Royall,” Aurora & Pennsylvania Gazette. Despite the crime occurring in DC, the opposition to Royall was desperate to find any relating code to try to punish her.

- ^ James A. Cox, "Colonial Crimes and Punishments,” The Colonial Williamsburg Official History & Citizenship Site. Spring 2003. Accessed March 21, 2017.

- ^ “The motion made by the Counsel for Mrs. Royall, in arrest of judgment, was argued in our Court on Tuesday, by Mr. Coxe,” Daily National Intelligencer, Jul. 31, 1829.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Lloyd Duhaime, "Ducking Stool Definition:," Duhaime.org, Accessed March 28, 2017

- ^ “Mrs. Royall,” The Daily National Intelligencer, Aug. 1, 1829.

- ^ In2013dollars.com

- ^ Earman, “An Uncommon Scold: Treasure-Talk Describes Life of Anne Royall.”

- ^ Carolina Observer. Aug. 27, 1829.

- ^ Earman, “An Uncommon Scold: Treasure-Talk Describes Life of Anne Royall.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Walking Tour: Women of Arts and Letters,” Association for the Preservation of Historic Congressional Cemetery, 2007.

- ^ Ibid.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)