The March King Steps Down

“Chicago wants the earth and the fullness thereof. She has the World’s Fair, Theodore Thomas, and now she has John Philip Sousa, Washington’s scholarly and accomplished musician, brilliant and versatile composer, and, more, the director par excellence of the United States Marine Band”

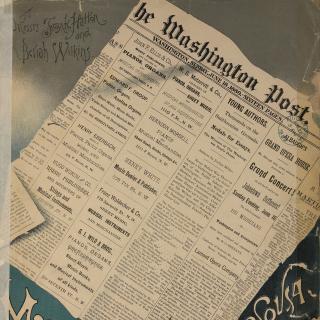

—The Washington Post, October 23, 1892

In the summer of 1892 Washingtonians had their hearts broken. After 12 years of conducting the United States Marine Band, John Philip Sousa, D.C. native and beloved conductor, submitted his resignation to the U.S. Marine Corps. He was leaving for Chicago, where he accepted an offer to serve as musical director of the “finest military concert band that the world can produce” (later named “Sousa’s Band”).[1]

Sousa’s decision to leave the Marine Band had been a difficult one, based mainly on salary conflicts with Congress. His ties to the ensemble were deeply engrained and dated all the way back to his birth in 1854. In fact, he was born “under the very shadow of the Marine Barracks” in Washington, and “among the first sounds to greet his infant ears were the strains of the Marine Band."[2] His father, Antonio Sousa, had played trombone in the Marine Band from 1854 until 1879, and he made 13-year-old John Phillip Sousa enlist into the ensemble as an apprentice in order to keep him from joining a circus band.[3] Minus a six month absence, Sousa played in the Marine Band until he was 20 years old. In 1880 at the age of 26, he was offered and accepted—by telegram—leadership of the Marine Band, making him the ensemble’s 17th, and first American-born, leader.

From his very start as music director of the Marine Band, he was well-loved and respected. The October 2, 1880 edition of the Washington Post announced:

“[Sousa] is well and favorably known by a large class of our best citizens and all doubts as to his capabilities on the score of youth or inexperience may be dismissed, as persons capable of judging will soon learn for themselves." [4]

Any skeptical Washingtonians soon saw Sousa not only elevate the quality of the Marine Band, but also dedicate himself to bolstering the D.C. music scene. Sousa rose to a status of extreme respect and loyalty in Washington, and the public revered him endlessly. It should be no surprise then, that when Sousa submitted his formal resignation to the Marine Corps in 1892, Washingtonians were immediately shocked and angered by his decision—even the newspapers were expressing their…well, blunt opinions on the matter:

“The Marine Band remains with us, it is true; that is a permanent fixture. But the man who made it musically, even if he did not originate it something like a century ago, is gone. Chicago got him. By the way, Chicago seems to get everything nowadays except the World’s Fair appropriation, and her chances are fair for that.” —The Washington Post, July 31, 1892

Clearly, Washingtonians were irritated with the City of Chicago for allegedly stealing Sousa from them, but they still made an attempt to give him the send-off he deserved. Leading citizens in D.C. wrote a letter expressing their appreciation and respect for Sousa’s past work and asked if he might exhibit his skill one more time at a testimonial concert.[5] Sousa accepted the honor, and the first of two farewell concerts was held on July 29, 1892 at the New National Theatre. Just to set the scene for the magnitude of this event, it was the sole musical entertainment offered in Washington D.C. for the entire week in order to “assist the general desire to testify to the appreciation of Mr. Sousa’s services in the city."[6]

The National Theatre was two-thirds full on that Friday night, despite the fact that Washington was in the midst of a heatwave which skyrocketed the pre-air conditioning city into the 90’s. (The public’s determination to see Sousa, in what would have undoubtedly been an incredibly hot and stuffy theatre, should speak to his popularity among Washingtonians).

With an eager audience filling the sweltering National Theatre, the curtain rose “disclosing the Marine Band grouped in an artistic wood scene."[7] Sousa conducted the ensemble in several pieces, including his crowd-favorite composition Chariot Race. The audience erupted in applause after every piece, causing Sousa to come out on stage in appreciation again and again. During one of these ovations, Walter Smith, the first cornet player who was also resigning in order to join Sousa’s new band, rose up from his seat and started to address Sousa:

“You have been the leader of the band for the past twelve years, during which time there has been no recognition of the appreciation of your services on the part of the band except the cheerfulness with which they have performed their duties under your orders. We want you to carry away with you some practical evidence of our feeling toward you and ask you to accept this baton and the accompanying scroll on which are engrossed the names of the active members of this band.”

Sousa graciously accepted the 17⅛ inch baton which was capped with the Marine Corps’ globe and eagle emblem, and engraved with the words: “John Philip Sousa—presented by members of the U.S. Marine Band as a token of their respect and esteem. July 29, 1892."[8] (Since Sousa’s daughters returned the baton to the Marine Band in 1953, it is traditionally passed from Director to Director in each Change of Command ceremony).

Sousa announced that he felt an encore would be the best use for his new baton, and subsequently conducted the band in Approach and Retreat of the Salvation Army. After this piece, the audience erupted again, shouting for Sousa to give a speech. He quietly stepped to the edge of the stage and said, “If I have accomplished anything for the good of music in the past twelve years, I will not spoil it now with a speech.” He then turned around and closed the program with Hail Columbia.[8]

The very next afternoon, July 30, 1892, Sousa conducted his final concert of the Marine Band in pouring rain on the South Lawn of the White House. The atmosphere on the lawn was of both melancholy and joy as the crowd, including President Benjamin Harrison, watched Sousa’s Marine Band career come to a close.

“In spite of threatening clouds the green lawns were crowded with people, and even after the raindrops began to patter down upon them they hoisted their umbrellas and staid. It looked as if an army of black mushrooms had camped out on the green sward, while the heavens wept, presumably from sorrow.” —The Washington Post, July 31, 1892

Ironically, the most joyous moment of the performance was the incredibly successful premiere of Sousa’s Belle of Chicago March…Washingtonians must have put their newfound disdain of Chicago aside for a couple minutes to enjoy “The March King’s” new work. Through the rain, the crowd stayed put on the grass until the very end, and the “bandsmen, being marines and consequently more or less waterproof, played away” until the storm worsened, forcing the band to “seek shelter under the portico of the White House.”[9] Despite the conditions, the audience broke into excited applause after every piece.

At a reception following the performance, Sousa would receive his official honorary discharge, and President Harrison, followed by hundreds of others, would line up to shake Sousa’s hand and send their well wishes to their beloved conductor. But before the reception could commence, Sousa had one last duty to the U.S. Marines. He raised his baton and “with the customary rendition of Hail Columbia, the last concert of the Marine Band under the directorship of John Philip Sousa came to an end."[10]

Footnotes

- ^ The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. 1892. “SIGNED TO CHICAGO: John Philip Sousa to Leave Washington in August,” July 8. https://search.proquest.com/hnpwashingtonpost/docview/138764223/abstrac….

- ^ The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. 1892. “CHICAGO HAS OUR SOUSA: But the Marine Band Is Still with Us in All Its Glory.” October 23, sec. General. https://search.proquest.com/hnpwashingtonpost/docview/138899239/abstrac….

- ^ “John Philip Sousa.” 2017. Accessed September 18. http://www.marineband.marines.mil/About/Our-History/John-Philip-Sousa/.

- ^ The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. 1880. “THE NEW BAND LEADER: Mr. John Sousa Yesterday Appointed in Schneider’s Place,” October 2. https://search.proquest.com/hnpwashingtonpost/docview/137786874/abstrac….

- ^ The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. 1892. “TENDERED TO SOUSA: Final Testimonial of Washingtonians to John Philip South.,” July 15. https://search.proquest.com/hnpwashingtonpost/docview/138846990/abstrac….

- ^ The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. 1892. “The Sousa Testimonial Concert.” July 24, sec. General. https://search.proquest.com/hnpwashingtonpost/docview/138695495/abstrac….

- ^ The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. 1892. “THE BAND’S GIFT TO SOUSA: A Now Baton as a Mark of Esteem of Their Old Leader,” July 30. https://search.proquest.com/hnpwashingtonpost/docview/138896306/abstrac….

- ^ The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. 1892. “THE BAND’S GIFT TO SOUSA: A Now Baton as a Mark of Esteem of Their Old Leader,” July 30. https://search.proquest.com/hnpwashingtonpost/docview/138896306/abstrac….

- ^ The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. 1892. “SOUSA’S FAREWELL TOOT: Last Appearance of the Marine Band Under His Baton,” July 31, sec. General.

- ^ Ibid.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)