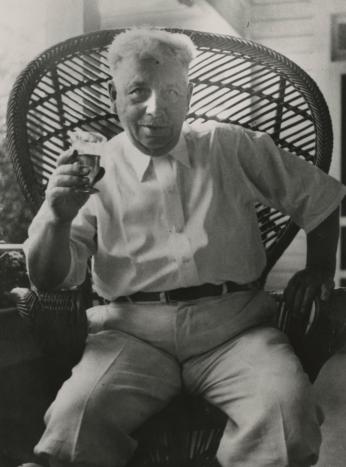

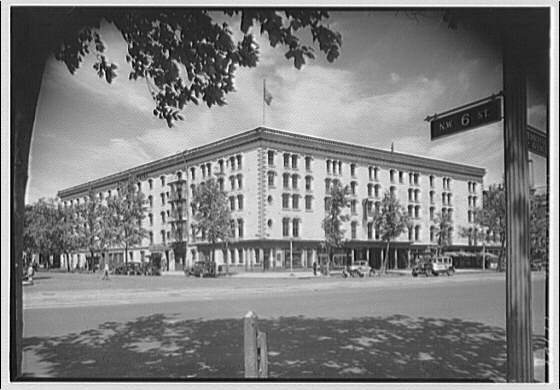

Washington’s Godfather: "Gentleman Gambler" Jimmy Lafontaine

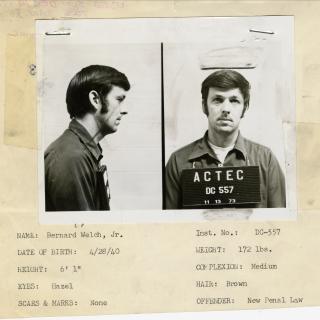

In December 1931, Jimmy Lafontaine was out for a walk near his SW Washington home. The 63-year-old was passing along the road, perhaps contemplating his upcoming prison sentence for tax evasion, when a car pulled up. “Is that you, Jimmy?” asked a passenger. Upon approaching the vehicle, Jimmy was bludgeoned, blindfolded, and whisked away to a “backwoods cottage in Virginia."[1]

The kidnappers, members of Philadelphia’s Boo Boo Hoff Mob, put a $40,000 ransom on Jimmy and awaited what they hoped would be a big payday from Jimmy’s associates. As the hours ticked by, however, they became more anxious while Jimmy remained relaxed. According to an account published later:

He whiled away the time napping, telling stories and puffing on his Havanas. To kill time, he suggested that they play some hearts. Mr. Jim beat them out of several thousand dollars for which he took a marker. On the fifth day the kidnappers began getting nervous. Mr. Jim, on the other hand, was enjoying himself immensely. He was playing cards against three of the biggest patsies he had ever seen. Finally, one of the men blew his stack. "Why doesn't somebody pay your ransom?" he demanded. "That's easy," said Mr. Jim. "I'm the only guy I know who's got $40,000, and nobody knows where I keep my money. But I'll tell you what. You take me home, and I'll get your money for you."[2]

The mobsters drove Jimmy back to his modest childhood home at 470 Maryland Ave. SW and waited as he went inside. Although Jimmy could have made a run for it, he wasn’t one to break a promise:

…Mr. Jim strolled into the house, kissed [his wife] on the cheek as though he had been away on a business trip, walked back to the car with 40 thousand-dollar bills. He counted out 36 of them and tucked the other four back in his pocket. "These are what you owe me for the hearts game," he said and walked away.[3]

When one thinks of the gambling scene in the 1920s, 30s, and 40s, the likes of Al Capone, Frank Costello, and Bugsy Siegel immediately spring to mind. However, the District had its own gambling godfather — Jimmy Lafontaine. He couldn’t have been further from the American gangster archetype. Though his extralegal line of work inevitably brought him unwelcome brushes with mobsters and the law, his story is not one of bootlegged booze or mysterious murders. Rather, he’s most often remembered for his charity and reputation as Washington’s “gentleman gambler.”

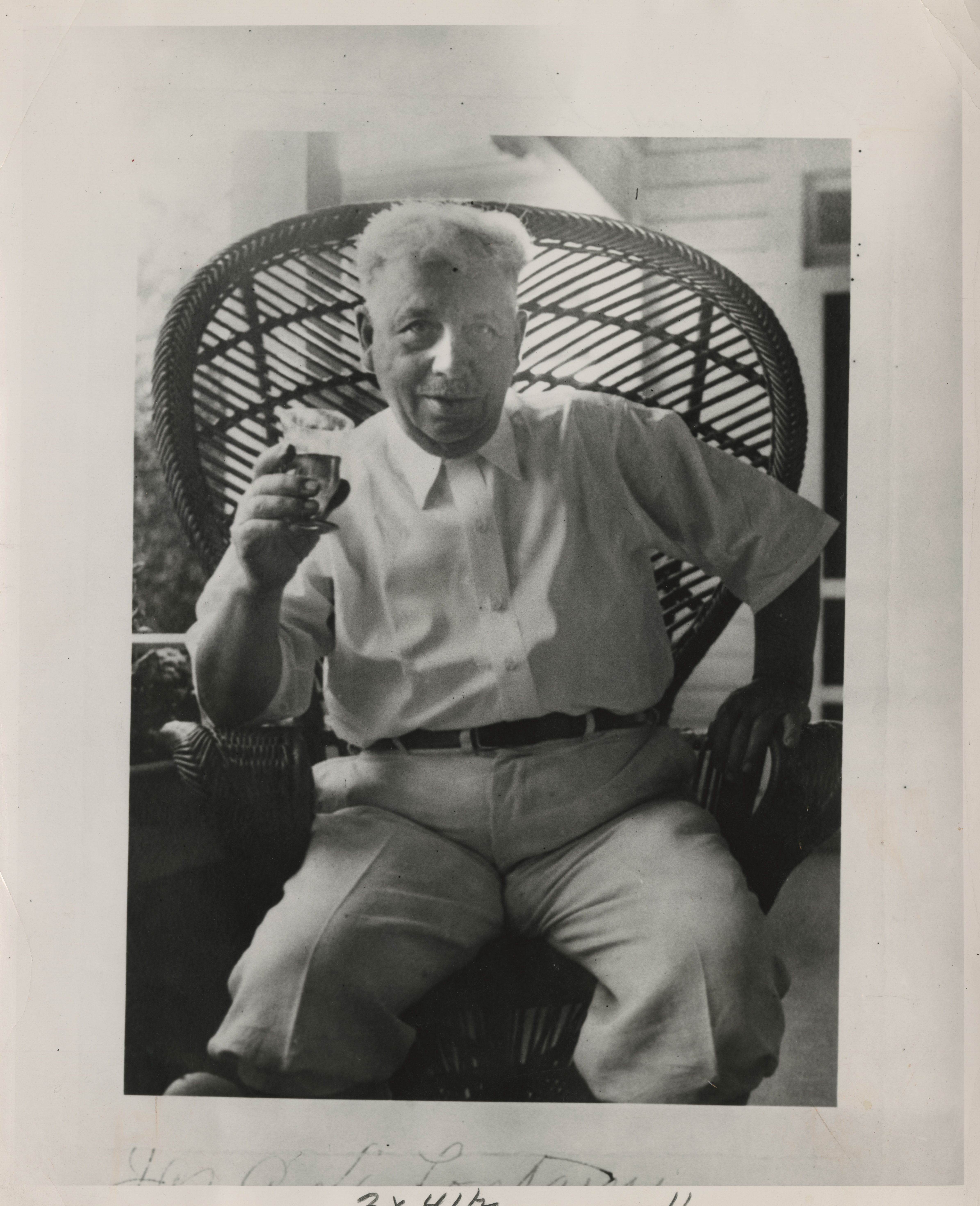

In 1917, Jimmy began buying up property on the corner of Eastern Ave. and Bladensburg Road, on the border between the District and Prince George’s County, Maryland. By the time he was done, he had converted an aging mansion into a rough but ready casino, which enjoyed a bustling business. Clientele included some of Washington’s biggest movers and shakers. Indeed, for 30 years, The Maryland Athletic Club—commonly known as Jimmy’s Place—was the place to gamble in the Washington area and beyond. At its height, it was the largest casino between Saratoga, New York and Palm Beach, Florida.[4]

Geography afforded Jimmy’s Place certain advantages. The casino’s driveway was in D.C., while the building sat in Maryland. This proved quite convenient on occasions when police received complaints as patrons simply fled a few yards to the other jurisdiction. Similarly, police in both jurisdictions – a number of whom were also patrons of Jimmy’s Place themselves – were known to claim it lay outside of their jurisdiction.[5]

Beyond location, the key to Lafontaine’s success may have lay in lessons he learned years earlier when he operated a short-lived establishment in Jackson City, a notoriously rough-and-tumble neighborhood in Arlington. While there, Jimmy observed that many people who opposed gambling did not take issue with gambling in itself. Instead they took issue with the criminal activities, which were often associated with gambling. So, if he could keep criminal elements (besides, you know, the illegal gambling itself) away from his casino, then it was less likely to be a target of police.

With that in mind, the Maryland Athletic Club had a few very strict rules:

Alcohol was banned and every single patron was frisked for flasks before entry. While other Prohibition-era casinos also operated speakeasies, Jimmy’s menu was limited to “a pretty good beef stew.”[6]

Likewise, guns were not permitted, either. Memorably, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and his men once kicked up a fuss when they were asked to surrender their pistols but Jimmy held his ground. Desperate to gamble in a place some might have demanded they raid, the G-men gave in.[7]

Finally, Jimmy’s Place also banned women. According to an 1891 report by the D.C. police, “lewd women, using vile and filthy language,” frequented Jackson City and presented “a disgusting spectacle.” So, it seems Jimmy’s ban on women was an anachronistic – if also supremely sexist – attempt at avoiding such “spectacles” at his new spot across the river.

A casino with no booze, weapons or women? Strange but true… and the peculiarities didn’t end there.

As Charles Price, the son of Jimmy’s right-hand man, recalled, Jimmy Lafontaine was known to give refunds on gambling losses.

It was not uncommon for a weeping woman to show up at the door and claim that her husband had blown their life savings the night before. To get a refund, the wife had to bring back a snapshot of her husband and agree to make sure that he would never return to the casino. This was a practice other casino operators considered laughable.[8]

Jimmy stood by this policy even after someone masquerading as the wife of a regular received a refund of $400.[9] While particularly troubled gamblers were refunded and banned from future visits, less tragic losers were comforted with free meals and rides back to Washington.

While others may have scoffed, Lafontaine’s policies turned out to be very good for business. Though he paid out a small fortune to informants who warned him of upcoming raids, and bribes to officials, Jimmy’s Place was a cash cow.

As such, the proprietor did quite well for himself and was very generous with his take. Over the years, Lafontaine developed a reputation as a D.C. Robin Hood of sorts. As a friend recounted decades later:

“[Jimmy] would be riding and see an institution, no matter what denomination… he would ask to stop and hand me a roll of bills in an envelope, telling me to just go in and put them on the desk.”

Aside from these random acts of philanthropy, Jimmy was known to have “pet charities” in Cuba and up the eastern seaboard.[10]

All this ensured the illegal and infamous casino’s longevity and contributed to Jimmy’s legend. However, all eras must eventually come to an end. In 1939, the Boo Boo Hoff Mob muscled in on Jimmy’s Place. While they kept Jimmy as the face of the operation, the gang took the profits. The Bladensburg Road casino saw bets for another eight years before closing in 1947, and Jimmy Lafontaine passed two years later.

Newspapers throughout the area published long obituaries honoring Jimmy but despite his legendary status, Jimmy’s legacy faded fast. On Feb. 5, 1955, firefighters torched Jimmy’s Place to clear the land for the construction of a Giant Food Stores distribution center.[11] Today, the site is occupied by warehouses. Few passersby would have any idea that the spot was once home to an institution of D.C. nightlife and the pride of the gentleman gambler.

Footnotes

- ^ Walter Haight, “Underworld Gives Jimmy a Bad Time," The Washington Post and Times Herald (1954-1955), Jan. 21, 1955, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post., Charles Price, "Mr. Jim Made a Million From a Casino Brooking No Booze, Women or Guns," Sports Illustrated, Oct. 11, 1976, 150.

- ^ Price, “Mr. Jim Made a Million.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Walter Haight, “Gamblers Found Action at Jimmy’s,” The Washington Post and Times Herald (1954-1955), Jan. 17, 1955, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ Walter Haight, “Jimmy’s Choice of Site a ‘Natural,’" The Washington Post and Times Herald (1954-1955), Jan. 19, 1955, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ Leonard Hughes, “Gamblers Once Thrived in the City,” The Washington Post (1974-Current file), Sep. 30, 1993, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ “Jimmy LaFontaine Dies at 81,” The Washington Post (1923-1954). Nov. 22, 1949, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post, 1.

- ^ “Monte Carlo,” The Evening Star (Washington), Dec. 16, 1891, NewsBank.

- ^ Price, “Mr. Jim Made a Million.”

- ^ Walter Haight, “Women Were Banned at Jimmy’s,’" The Washington Post and Times Herald (1954-1955), Jan. 20, 1955, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ Walter Haight, “Firemen Put Torch to Jimmy's Place,’" The Washington Post and Times Herald (1954-1955), Feb. 6, 1955, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)