Poe's Washington Excursion

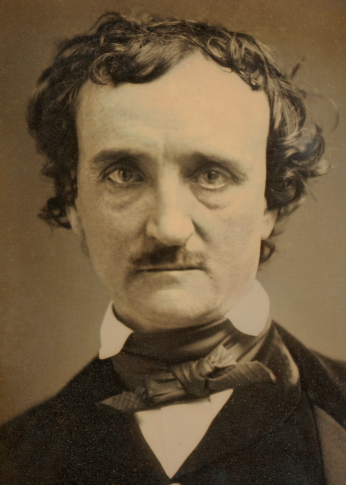

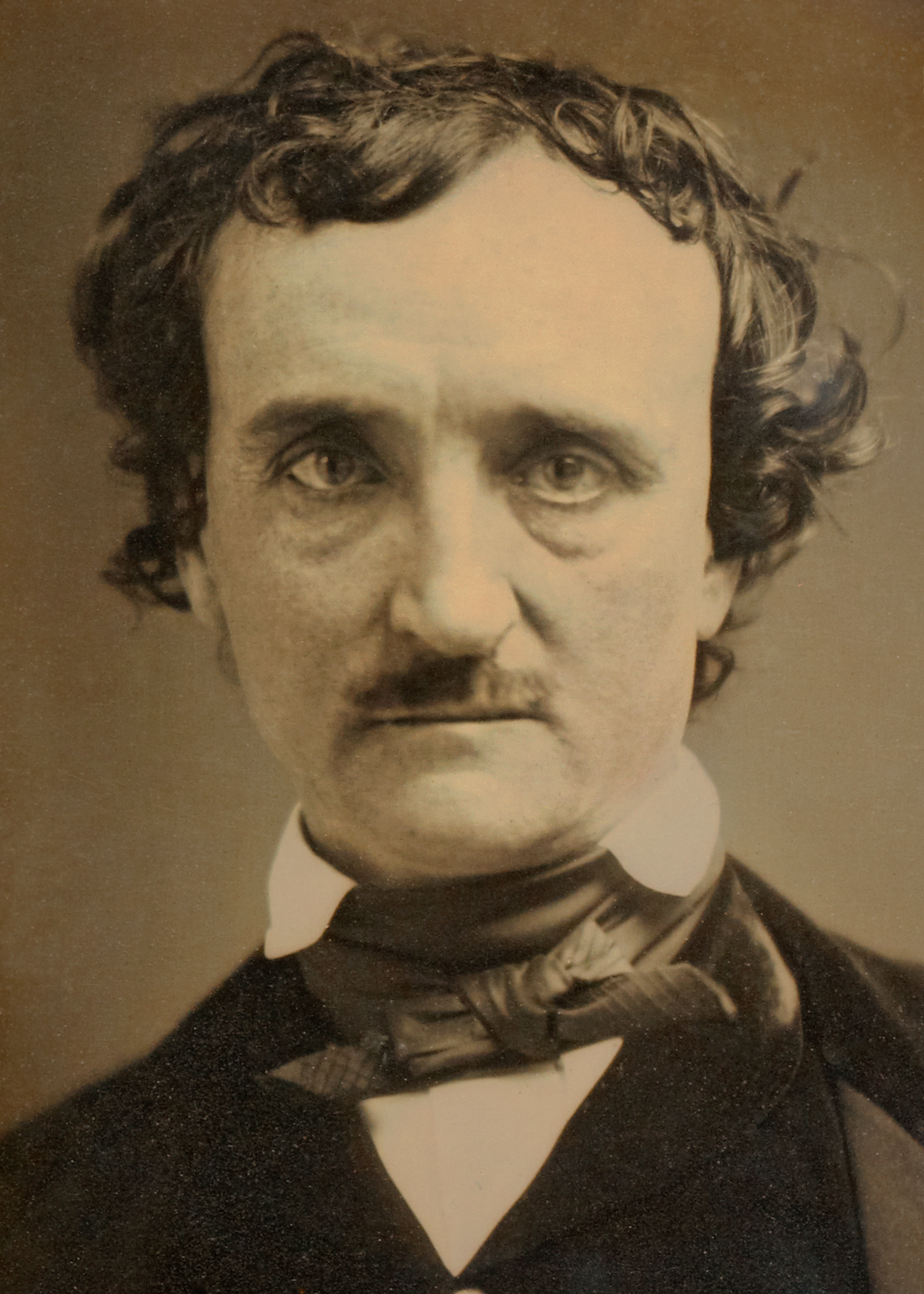

“I became insane, with long intervals of horrible sanity” –Edgar Allan Poe

The celebrated, yet ever tormented, writer Edgar Allan Poe, famously spent much of his life living in Baltimore and Richmond, but he surprisingly spent very little time in D.C. despite residing in such close proximity. He did however have one…interesting encounter in Washington.

Poe had many jobs both writing and editing for various magazines in his early years. Because of his, let’s say, brutally honest literary critiques, Poe found staying at any one magazine for a long period of time nearly impossible, and discovered that his critiques led many of his contemporary colleagues, including Longfellow and Emerson, to regard him as a “literary troublemaker” who was “kicking up dust in his commentaries.”[1] This constant state of instability eventually led Poe to determine that he needed to find a job that could provide him with more financial security.

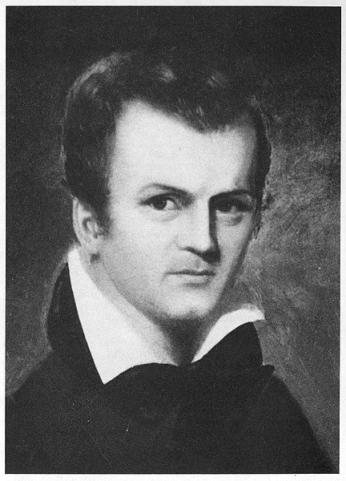

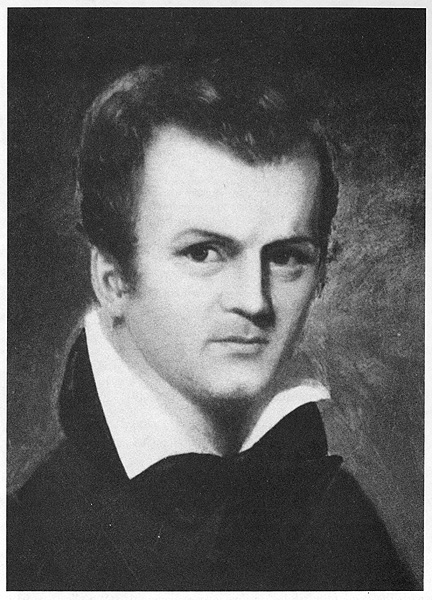

In 1841, Poe’s friend and fellow writer, Frederick William Thomas, had secured a clerkship at the United States Treasury Department in Washington, D.C. Thomas was rewarded with this position by President John Tyler as compensation for the campaign work Thomas had done in support of the late President William Henry Harrison.

Thomas soon wrote to Poe suggesting that maybe a government job could offer the stability he needed:

“How would you like to be an officeholder here at $1,500 per year payable monthly by Uncle Sam who, however slack he may be to his general creditors, pays his officials with due punctuality. How would you like it? You stroll to your office a little after nine in the morning leisurely, and you stroll from it a little after two in the afternoon homeward to dinner, and return no more that day." [2]

Despite his aspirations to create his own literal journal, the suggestion of a government job was intriguing to Poe with its promise of easy money. As a struggling writer, easy money was much needed, and would help give him mental stability as well as financial security. (Understandably, Poe wasn’t the only great American poet tempted by government work and was later followed by Walt Whitman among others).

In September 1842, Thomas paid Poe a visit at his home in Philadelphia to discuss the possibility of swinging Poe a government job through a connection with the President’s son, Robert. Poe agreed to meet with Robert Tyler at Congress Hall in New Jersey the next day, but failed to show up for the meeting. The poet explained his absence in an apologetic letter dated September 21, 1842:

“The will to be with you was not wanting—but, upon reaching home on Saturday night, I was taken with a severe chill and fever—the latter keeping me company all next day. I found myself too ill to venture out, but, nevertheless, would have done so had I been able to obtain the consent of all parties.” [3]

Whether Poe was really sick, or just too hungover to leave home, is still contested today. Despite this clear sign that Poe was not cut out for a government position, Tyler, being “remarkably fond of poetry,” recommended him for a position at the Customs House in Philadelphia.

In November, following this generous recommendation from the President’s son, Poe went down to the Customs House to see the collector Thomas S. Smith. For reasons unclear to Poe at the time, there was significant confusion over his name, which had apparently been misprinted as “Pogue” on the paper listing expected appointments, and he was forced to wait. After waiting two days for a call that never came, Poe went back only to find out that Smith had been instructed to refrain from removing any employees, which meant he would not have an open position for Poe's appointment.[4] Poe mentioned that Robert Tyler had personally requested that Poe be appointed, and Smith laughed at the suggestion saying that he only took orders from President Tyler. Smith then led Poe on for a month by continually telling him that he would swear Poe in on a certain day, and then refusing to do so. Soon Poe came to learn that Smith was strongly anti-President Tyler, and was abusing his position by only appointing Whigs.[5] Enraged by the way he was treated at the Customs House, Poe prepared to visit Washington with the goals of securing the Customs House job by speaking with Robert and President Tyler, as well as getting government backing for his own literary magazine.

In March 1843, Poe arranged a visit to the White House and traveled to the District. Here’s where the story gets a little hazy; while there is no doubt that Poe did indeed come to Washington with the intention of speaking with the President, there seems to be confusion over what exactly happened once he arrived.

Accounts vary but the general consensus is that Poe starting drinking excessively after arriving at his hotel in D.C. Some say that he then proceeded to show up to the White House meeting drunk where he made a fool of himself.[6]

Writer and Poe scholar Paul Clemens describes the White House meeting, as a two day affair:

“He showed up for the appointment quite intoxicated. He was wearing his cloak inside out. He was disheveled. And fortunately for Poe, the president’s son Robert Tyler, intercepted him first and said ‘why don’t you come back in a few days.’ When Poe showed up for the second meeting, he was quite sober and conducted himself very well—at first. But then, for some bizarre quirk, he decided to use the opportunity of this meeting not just to secure the President’s help in getting him a position in the Customs House, but to solicit magazine subscriptions from him.” [7]

Another account suggests that Poe might have been so depressed over finding out that the Customs House had received 1,200 applications, that he drank to excess and never made it to the White House at all. One friend wrote that “on the first evening [Poe] seemed somewhat excited, having been persuaded to take some Port-wine,” while another recalled that Poe was, “seedy in appearance and woe-begone…he said he had not had a mouthful to eat since the day previous, and begged me to lend him fifty cents to obtain a meal.”[8]

Poe himself seemed to confirm these suspicions of a wild, drunken night in a March 16, 1843 apology letter written to Frederick William Thomas in which he asks forgiveness for speaking inappropriately, wearing a cloak turned inside out, owing money to a barbershop, and for “making a fool of [himself]” in someone else’s home due to the “excellent Port wine.”[9] Curiously, Poe makes no reference to actually visiting the White House in this letter, and instead closes it by pleading that Robert Tyler still consider him for the government job, which he would gladly, and promptly, accept.

Interestingly, in a letter written back to Poe on March 27, Thomas mentions that he had the opportunity to speak with the President, who asked many questions about Poe and spoke very kindly of him. According to Thomas, during that meeting a servant came and privately told Tyler about Poe’s “frolic from a man who saw [him] in it.” Thomas claims that he “made light of the matter,” and the President “seemed to think nothing of it” and that “he seem[ed] to feel a deep interest in [Poe].”[10]

Considering that it would not have actually arrived for at least a week or two, Thomas’ letter did little to ease Poe’s mind. Apparently in a deep panic over his prospects for the government job, the poet wrote to Robert Tyler expressing his belief that Judge Blythe, the Democrat recently appointed by the Senate as the new head of the Philadelphia Customs House, would appoint him with another recommendation from Tyler. Robert responded that he would be gratified to recommend Poe for the position and that he was “satisfied that no one [was] more competent, or would be more satisfactory in the discharge of any duty connected with the office.”[11]

Whether it was because of his ill-fated Washington trip, or some other unknown political reason, ultimately Judge Blythe did not appoint Poe despite Robert Tyler’s recommendation. Poe never wound up with any other government job or his own literary magazine. And, perhaps that is fitting. It’s a strange thought to imagine Edgar Allan Poe, the tormented artist, as a government bureaucrat.

Footnotes

- ^ http://poecalendar.blogspot.com/2009/09/poe-and-politics.html

- ^ Collins, Paul. 2014. Edgar Allan Poe: The Fever Called Living. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 54.

- ^ “Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore - Works - Letters - E. A. Poe to F. W. Thomas (September 21, 1842).” https://www.eapoe.org/works/letters/p4209210.htm.

- ^ Although John Tyler had previously been frustrated with Andrew Jackson’s employment of the Spoils System (appointing family and friends to government positions as a reward for campaign help), he resorted to the practice himself in 1843 in an attempt to annex Texas. Because Poe went to the Customs House in 1842 (a year before Tyler would find patronage acceptable), it is not unreasonable to suspect that Tyler had issued a notice against the act of removing people from their positions in order to hire friends—an act which he claimed to find despicable.

- ^ “Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore - Works - Letters - E. A. Poe to F. W. Thomas (November 19, 1842).” https://www.eapoe.org/works/letters/p4211190.htm.

- ^ http://www.thirteen.org/13pressroom/press-release/american-masters-edga…

- ^ Edgar Allan Poe - His Own Worst Enemy. 2017. Accessed October 5. https://www.biography.com/video/edgar-allan-poe-his-own-worst-enemy-208….

- ^ Collins, Paul. 2014. Edgar Allan Poe: The Fever Called Living. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 54-55.

- ^ “Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore - Works - Letters - E. A. Poe to F. W. Thomas and J. E. Dow (March 16, 1843).” https://www.eapoe.org/works/letters/p4303160.htm.

- ^ “Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore - Works - Letters - F. W. Thomas to E. A. Poe (March 27, 1843).” https://www.eapoe.org/misc/letters/t4303270.htm.

- ^ “Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore - Works - Letters - R. Tyler to E. A. Poe (March 31, 1843).” https://www.eapoe.org/misc/letters/t4303310.htm; Tschachler, Heinz. 2013. The Monetary Imagination of Edgar Allan Poe: Banking, Currency and Politics in the Writings. McFarland. p 102.

![White House, 1846, Plumbe, John, photographer. [President's house i.e. White House, Washington, D.C., showing south side, probably taken in winter]. , ca. 1846. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2004664421/. (Accessed October 12, 2017.) White House, 1846, Plumbe, John, photographer. [President's house i.e. White House, Washington, D.C., showing south side, probably taken in winter]. , ca. 1846. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2004664421/. (Accessed October 12, 2017.)](/sites/default/files/styles/embed/public/white_house_1846.jpg?itok=0Z_PDidR)

![White House, 1846, Plumbe, John, photographer. [President's house i.e. White House, Washington, D.C., showing south side, probably taken in winter]. , ca. 1846. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2004664421/. (Accessed October 12, 2017.) White House, 1846, Plumbe, John, photographer. [President's house i.e. White House, Washington, D.C., showing south side, probably taken in winter]. , ca. 1846. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2004664421/. (Accessed October 12, 2017.)](/sites/default/files/white_house_1846.jpg)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)