No Bridge for Three Sisters

“It has been possible in this town to say two words that can stop, start or totally destroy a conversation about local affairs: ‘Three Sisters,’…a bridge that one cannot see but which one can feel very strongly about. And its implications touch politics, home rule, money, planning, conservation, freeways, subways, housing and Presidents of the United States – among other things.” – The Washington Post, August 22, 1970[1]

Among those “other things” is a supposedly cursed cluster of rock islands on the Potomac River, after which the bridge was named. The origin story dates back hundreds of years and goes something like this:

Late one night, the three young Native American women snuck away from their family and friends to avenge the deaths of their brothers in regional warfare. Or to escape arranged marriages. Or to unite with lovers from an enemy tribe. (The folklore varies.)

Motives aside, their plan required them to cross the Potomac River. In the quiet and calm of the night, the three sisters crept into the water with their makeshift raft and began to carefully paddle across – but their efforts were not without an audience.

The local medicine man had taken notice of their departure and followed them to the river’s edge, spying silently from behind the trees. Livid, he watched their slow and certain progress. The sisters smiled proudly at one another in the faint moonlight, halfway across, when suddenly the man conjured a ferocious storm that swelled the river, splintering the raft and hurling the sisters into the water.

Lightning flashed in blinding colors around them, confidence melting into panic as their end drew near. Clasping each other’s hands, the sisters made a promise: if they could not cross the river here, then never again would anyone else.

And then the river swallowed them whole.

By morning, the storm had subsided and unveiled three large rocks on the river’s surface: the Three Sisters Islands.

Over the centuries, Washingtonians might have found reason to believe that the site was, indeed, cursed. Between the late 18th century and the early 20th century, there had been several proposals to build a bridge in the vicinity of the Three Sisters Islands.[2] However, none of those projects materialized. Still, that didn’t stop planners from reawakening the idea in the 1950s.

In the mid-20th century, the national capital region saw dramatic shifts in how and where people were living. A big reason? Automobiles. According to historian Zachary Schrag: “auto-owning families took advantage of their mobility to move to the suburbs, and suburban families found that they needed cars.”[3] Census records show that the District’s population peaked in 1950, and then started to decline.[4] Meanwhile, the suburbs of Virginia and Maryland exploded.[5]

The suddenly burgeoning greater metropolitan area presented some issues, as Dorothea Andrews observed in The Washington Post in 1948. “Suburban living is naturally attractive to city-dwellers,” she explained. But, in the Washington area, “one of the knottiest problems planners face is the flow of traffic.” More commuters “funneling in from a wider and wider area, converging on Washington’s central business district” created gridlock. It was a simple, if also very difficult to solve problem: “The central business district cannot accommodate all the automobiles and public vehicles that would like to come into it.”[6]

Politics of the coming years would endeavor to puzzle through the unprecedented volume of regional commuters. In 1952, Congress delegated the puzzle over to the newly created National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) and National Capital Regional Planning Council (NCRPC). They, in turn, launched a joint effort to conduct the Mass Transportation Survey.[7]

Presented in 1959, the plan called for a 248-mile highway program, supplemented by metropolitan subway and bus networks.[8] The recommended highways would necessitate a new Potomac River bridge at the Three Sisters Islands. President Eisenhower’s Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 demonstrated national support for highways so much so that the Federal government committed to 90 percent of construction costs.[9]

Road- and bridge-happy highway planners got right to work. “The heart of their proposed system,” writes Schrag, “was the Inner Loop, a ring road around the core of the city.”[10] Several “legs” would feed in and out of the loop to allow commuters to circumvent congestion. One of these “legs,” was to cross over the Three Sisters Islands.[11]

While the Mass Transportation Survey called for both new highways AND a mass transit rail system, debates on their relative proportions continued. During the early 1960s, pro-transit lawmakers and pro-highway lawmakers attempted to push forward plans that favored one mode over the other. Under the Kennedy administration, the National Capital Transportation Agency advocated expanded transit and proposed dropping several of the major highway projects.[12]

Meanwhile, pro-asphalt lawmakers led by House D.C. Appropriations Subcommittee Chairman William Natcher (D-KY), continued to push for highways. As Natcher told the press in 1963, “Any effort to bring to a complete halt important highway projects is a serious mistake…. The approved freeways which have been considered by our committee from time to time, with funds appropriated, are a vital part of the future development of the District.”[13]

The various on-again, off-again proposals caused construction to stall, as the proposed freeways faced growing outcry from D.C. residents.

Taking up demonstration in a multitude of forms, residents banded together across the District. Perhaps the most famous coalition was the Emergency Committee on the Transportation Crisis (ECTC), led by Sammie Abbott, Reginald Booker, and future mayor Marion Barry. As freeway planners sliced and diced the city on their maps, it became clear that D.C.’s poor, black neighborhoods were most at risk. Decrying the injustice of building “white man’s roads through black men’s homes,” protesters argued that what these neighborhoods needed most was not highways to serve (mostly) suburban white commuters but reliable and accessible public transit.[14] With some white neighborhoods on the chopping block, also, ECTC grew into a biracial effort. As Abbott declared, “There are going to be whites with our black brothers on this,” refusing to neglect inner city well-being.[15]

Natcher, however, remained unmoved. Fiercely protective over the nation’s highway-spangled future, he took aim at “these little pressure groups and people downtown that want to destroy the highway program,” such as the ECTC.[16] Declaring it “time to stop this foolishness” in 1966, the Kentuckian threatened to withhold funding for the Metro system unless the road building project and the Three Sisters Bridge moved forward.

For highway advocates, the bridge came to symbolize the freeway movement as a whole, as it would connect complex highway systems on either side of the Potomac River.[17] If the bridge was finally built, their thinking went, it would clear the way for the other highway construction. Hence Natcher’s hardline stance: No bridge, no subway.

The bridge project was included in the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1968, but opposition continued.[18]

The situation came to a head in the summer of 1969 when the matter went before the D.C. City Council. Most members of the council opposed the bridge project. However, Natcher’s ultimatum put them in a tough spot. Voting ‘no’ on the bridge meant potentially sacrificing the Metro system.

July’s weary City Council meeting on the subject ended without consensus. Natcher continued to press Three Sisters Bridge construction “‘beyond recall’,” leading one incredulous opponent to remark, “‘Nobody can believe in a city government that bows to blackmail’.”[19] Bow, though, they did.

When council members met August 9th for a final vote on the Three Sisters Bridge, they were not alone at the city hall.[20] Surrounding the council and making all possible attempts to disrupt the vote were over 200 highway protesters. ECTC’s Sammie Abbott was the first to be arrested, followed by his chairman Reginald Booker. Some left per police orders, others were arrested and dragged out, but not before chairs were thrown and one protester hurled a small metal ashtray at Council Chairman Gilbert Hahn Jr.[21]

The disruptions did not change the expected outcome. The council voted 6-2 to approve the bridge and comply with the 1968 Highway Act, even as several members expressed remorse and “personal anguish” over the decision.[22] One said, “‘we are all painfully aware that [this] is no longer just a transportation issue but one that strikes at the very heart of the operation of this city’.”[23] Despite commendation from President Nixon, who supported subway construction and saw the bridge approval as a means to achieve it, Chairman Hahn lamented that the council “had no alternative.”

Councilwoman Polly Shackleton pointed to the inherent difficulties that the council faced as long as Congress controlled its purse strings:

“The significant thing about the fight was that congress showed us who was boss. Everybody was much too optimistic that we had power and really were a City Council. But when we get into a crunch, Congress predominates. That’s the way it is. We should have known it.”[24]

For many Washingtonians, the bridge debate was a disturbing reminder that despite the Home Rule Act of 1967, which created a presidentially-appointed city council, the District was still under the Federal government’s thumb. As one Washingtonian wrote to the Post, “Nothing manifests more clearly the need for home rule in Washington than does the highway-subway impasse. Under the cloak of balanced transportation, Mr. Natcher (D-Ky.) and his friends are demanding the construction of freeways that the District does not need or want…. It is not a matter of D.C. pride to fight Three Sisters Bridge and the North Central Freeway.”[25]

Physically injured in their arrests, Abbott and Booker immediately regrouped with the ECTC and decided to file a fresh lawsuit against the Three Sisters Bridge.[26]Still, as autumn rolled around, so did the bridge construction at long last. The ground breaking was set for mid-October.

Matt Andrea, a Georgetown University crew team member, approached Sammie Abbott with an idea. “‘What if students from Georgetown and other campuses occupied the islands?’” he proposed, and Abbott beamed at the suggestion. Together they handed out leaflets on campus like party invitations to a protest.[27]

What started as a handful of students camping on the islands with sleeping bags, snacks, and slogans such as “Stop the Bridge,” soon grew into a full-fledged anti-freeway, pro-subway demonstration.[28] To participants, the Three Sisters Bridge represented a glaring affront on D.C.’s citizens and residents, and, as one student reiterated, was “‘a key link in a freeway system which isn’t practical or viable way to alleviate the District’s traffic problem’.”[29]

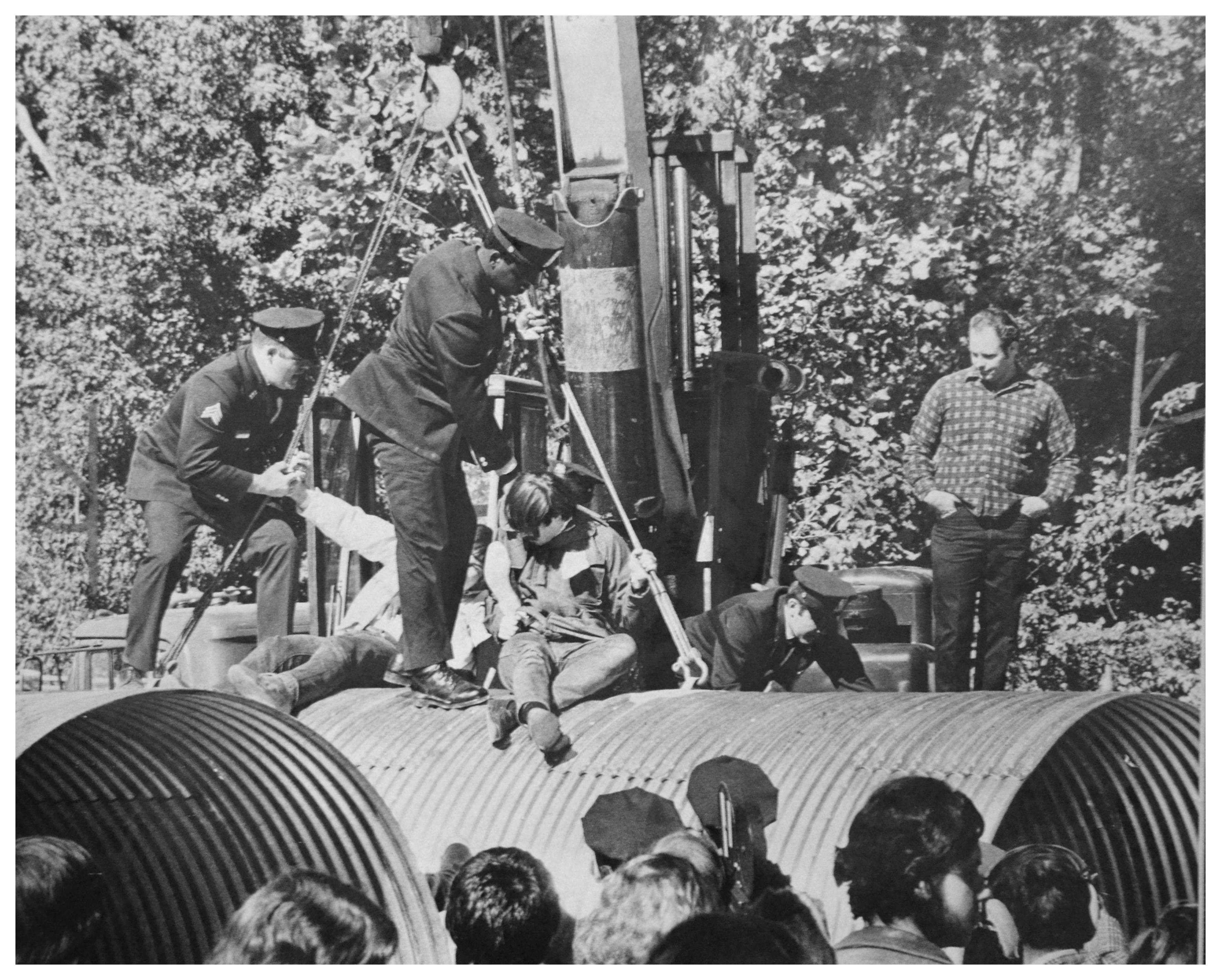

Over the next several weeks, the student protesters went from cheerfully picnicking on the riverbank to wrangling machinery. In groups of over 100, they clashed with police, construction workers, and physically barricaded bulldozers and pipes with their bodies.[30] Riot police waved their batons in the Potomac waters as protests continued into November.

All the frenzy and commotion on the river made a splash. Though construction on the bridge continued, the issue remained in the public eye. The D.C. Federation of Civic Associations filed a suit against the U.S. Secretary of Transportation, John Volpe, asserting that the decision to move forward with the bridge had been driven by politics, not by a proper needs assessment as required by federal law. Locals released a sigh of hopeful relief a few months later when U.S. District Court Judge John J. Sirica called “a halt to the bridge construction, this time until planning can be brought fully into line with federal laws and regulations.”[31]

Attentive to the ongoing strife, and subway funds still under Natcher’s lock and key for yet another year, President Nixon made multiple appeals for the Metro money to be surrendered in the fall of 1971.[32] Facing pressure from an exasperated White House, the House of Representatives collected themselves and held a seven hour debate in December. “His voice quivering with emotion,” Chairman George H. Mahon of the Appropriations Committee remarked on the “battle of principle,” earnestly philosophizing on whether “we want to kick the President of the United States in the teeth.”[33]

A point of confusion during the session concerned the extent to which the Court of Appeals might consider rehearing its bridge-halting decision, which Natcher had proclaimed as “outrageous.”[34] When it was announced that the Court refused any such gesture, the House moved to vote. To the dismay of the tenacious Kentuckian, the debate resulted in victory for the subway, with the final roll call recorded 195 to 174.[35]

Was the Three Sisters Bridge now scratched once and for all? Not quite. Because the span was still an essential ingredient to highway planning, District residents kept a vigilant eye on the riverbank as well as the neighborhoods at risk of demolition for road construction. On either side of the Three Sisters Islands, one could see the budding bridge piers.

But something big happened in the summer of ’72. It wasn’t a court ruling. It wasn’t a grassroots demonstration. It wasn’t a budgeting blunder.

In June, Hurricane Agnes boldly stormed her way up the East Coast. With a mischief not unfamiliar to the Potomac River, she paid an unruly visit to the Three Sisters Islands. The water rose and surged with torrential rain from every direction, swelling the river and swallowing the riverbanks whole.

When the storm subsided, something was different. The islands had not flinched, but their younger neighbors – the bridge piers – were nowhere to be seen. Since then, Washingtonians have cautiously wondered that perhaps those three sisters from that Native American legend had been serious. Maybe their spirits really were possessed in the islands and maybe they still meant what they said: If we cannot cross the river here, then never again will anyone else.

The Three Sisters Bridge was officially erased from regional highway plans in 1977,[36] and today the islands welcome friendly kayakers and canoe paddlers on the glistening Potomac waters.

Footnotes

- ^ Asher, Robert L. "The Three Sisters - and How They Grew." The Washington Post, August 22, 1970, A14. Access provided by ProQuest via dclibrary.org

- ^ Potomac River enthusiasts George Washington and Pierre Charles L’Enfant had set out to plan a federal city in the 1790s (Berg, Scott W. Grand Avenues: The Story of the French Visionary. Pantheon Books, NY. 2007). Singing praises of the magnificent waterway, L’Enfant jotted down notes for a bridge over the Three Sisters Islands to connect Georgetown’s burgeoning ports with the Virginia shore (Williams, Mathilde D. "The Three Sisters Bridge: A Ghost Span over the Potomac." Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 69/70 (1969): 489-509. www.jstor.org/stable/40067725.). Solicitation for such a span, however, was not assembled until the 1850s, due to abysmal conditions of cross-Potomac transit (Ellet, Charles, 1810-1862. Report On a Suspension Bridge Across the Potomac, for Rail Road And Common Travel: Addressed to the Mayor And City Council of Georgetown, D.C. Philadelphia: J. C. Clark, printer, 1852). Bridge expert Charles Ellet authored a report for a wire suspension bridge that would restore access to regional trade and travel (Ellet). Despite fitful but enthusiastic headway for a Three Sisters Bridge, the sobering turmoil of the Civil War wiped out any such prospect (Williams).

- ^ Schrag, Zachary M. The Great Society Subway: A History of the Washington Metro. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014. Pg. 17

- ^ Gilmore, Matthew B. "District of Columbia Population History." WordPress. Last modified August 2014. https://matthewbgilmore.wordpress.com/district-of-columbia-population-h….

- ^ Grymes, Charles A. "Population Growth." virginiaplaces.org. Last modified 2018. http://www.virginiaplaces.org/population/popgrowth.html In Northern Virginia, Arlington’s population had more than doubled during the 40s, from 57,040 to over 135,000, and the county added another 28,000 residents by 1960. Fairfax nearly tripled between 1950 and 1960, from 98,557 to 275,002.

- ^ Andrews, Dorothea. "Growth of Suburbs Snarls D.C. Traffic." The Washington Post, June 20, 1948, R8. Access by ProQuest via dclibrary.org

- ^ United States Congress: Office of Technology Assessment. Assessment of Community Planning for Mass Transit: Volume 10 — Washington, D.C. Case Study. 1976. https://ota.fas.org/reports/7612.pdf. Pg. 10-11

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Weingroff, Richard F. "Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956: Creating The Interstate System." Federal Highway Administration. Last modified Summer 1996. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/publicroads/96summer/p96su10.cfm.

- ^ Schrag, Zachary M. The Great Society Subway: A History of the Washington Metro. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014. Pg. 24

- ^ Schrag, Zachary M. The Great Society Subway: A History of the Washington Metro. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014. Pg. 43

- ^ Clopton, Willard. "Controversial Road Projects To Be Delayed: NCTA Plan Studied NCTA Tactics Protested Key District Road Jobs Are Delayed." The Washington Post, January 19, 1963, C1.

- ^ Clopton, Willard. "Rail Transit Plan Sent To Congress: President Asks Prompt, Favorable Action on Project." The Washington Post, May 28, 1963, A1.

- ^ Schrag, Zachary M. The Great Society Subway: A History of the Washington Metro. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014. Pg. 119-20

- ^ White Jr., Jack. "Freeway Foes Present Case to Council." The Washington Post, November 26, 1967, D1.

- ^ Asher, Robert L. "Halt to Subway Money Is Threatened If D.C. Freeway Foes Continue Attack." The Washington Post, August 9, 1966, A1.

- ^ The Washington Post. "Symbolism and the Subway." September 10, 1963, A18.

- ^ United States Congress, “Public Law 90-495.” 23 Aug 1968. Stat. 83; Sec. 23 (a) (1). Pg. 827 https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-82/pdf/STATUTE-82-Pg815.pdf

- ^ Eisen, Jack, and Irna Moore. "Bridge Vote Tied To Metro Funds: Metro Fate Tied to Bridge." The Washington Post, July 23, 1969, C1.

- ^ Eisen, Jack, and Irna Moore. "Fists Fly At Voting On Roads: Bridge Foes Erupt as City Bows to Hill." The Washington Post, August 10, 1969, A1.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ 91st Congress, 1st Session, Volume 115, Part 18. Congressional Record (Bound Edition). “Extensions of Remarks.” September 10, 1969, pg. 25102. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1969-pt18/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1969-pt…

- ^ Kijuchi, Kunio. "Letters to the Editor: Transportation Impasse." The Washington Post, August 1, 1969, A18.

- ^ Eisen, Jack, and Irna Moore. "Fists Fly At Voting On Roads: Bridge Foes Erupt as City Bows to Hill." The Washington Post, August 10, 1969, A1.

- ^ Jaffe, Harry. "The Insane Highway Plan That Would Have Bulldozed DC's Most Charming Neighborhoods." Washingtonian, October 21, 2015. https://www.washingtonian.com/2015/10/21/the-insane-highway-plan-that-w….

- ^ Colen, B. D. "Nearly 100 Bridge Foes 'Occupy' Three Sisters Islands: Students Lead Protesters Awaiting Start of Construction Today." The Washington Post, October 13, 1969, D1.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Jaffe, Harry. "The Insane Highway Plan That Would Have Bulldozed DC's Most Charming Neighborhoods." Washingtonian, October 21, 2015. https://www.washingtonian.com/2015/10/21/the-insane-highway-plan-that-w….

- ^ Asher, Robert L. "The Three Sisters - and How They Grew." The Washington Post, August 22, 1970, A14. Access provided by ProQuest via dclibrary.org

- ^ Eisen, Jack. "House Releases District Subway Funds: Leadership Rebuffed, 195 to 174." The Washington Post, December 3, 1971, A1.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Jaffe, Harry. "The Insane Highway Plan That Would Have Bulldozed DC's Most Charming Neighborhoods." Washingtonian, October 21, 2015. https://www.washingtonian.com/2015/10/21/the-insane-highway-plan-that-w….

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)