When D.C. Faced a Typhoid Epidemic

Ever wondered what those giant concrete cylinders lined up along Michigan Avenue are? Well, if you lived in D.C. at the turn of the twentieth century, they might have saved your life.

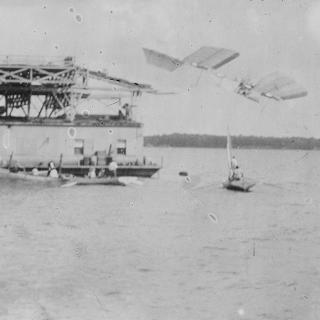

Those eye-catching cylinders are part of the now-defunct McMillan Sand Filtration Plant, built in 1905. It was the first system the District had in place to purify its water supply. Using the slow sand filtration method, raw water from the McMillan reservoir trickled through layers of sand, gravel, and stones until it was clean. The cylinders stored fresh sand to replace the top layer when it got too dirty from collecting pollutants. Beneath the surface level of the plant, water flowed through the “Cave of the Thousand Devils” (an expansive subterranean chamber so named by its construction workers), and into the city’s water mains, free of impurities.[1]

What kind of impurities? Beginning in the 1890s, typhoid was all over the headlines of Washington’s major newspapers. As new cases were reported daily, stories like “Epidemic of Typhoid” and “All Records Broken: Typhoid Fever Makes Rapid Gain” filled the front pages seemingly every week.[2] In 1900, Professor H.D. Geddings, acting director of the Marine Hospital Service’s hygienic laboratory warned the public:

Some method should at once be adopted for the purification of the District water supply. Not only is typhoid fever epidemic practically, but the city of Washington enjoys the unsavory reputation of having one of the largest death rates from typhoid in the United States, and typhoid being a strictly preventable disease, this state of affairs is a reproach and must soon seriously militate against the prosperity and advancement of the city.”[3]

As Geddings suggested, the cause of this health emergency was D.C.’s drinking water.

For decades, the city's water had flowed through the Washington Aqueduct, which dated to 1853 and was still very much a work in progress. It started with a diversion dam spanning the Potomac River, just above Great Falls. From there, water passed through the Dalecarlia Reservoir and the Georgetown Reservoir. Once the McMillan Reservoir was built in 1902, all that raw Potomac water settled there before going straight to people’s faucets.[4]

The result could be unpleasant or, in the worst cases, deadly. The Washington Post painted a clear picture of the murky water coming out of the tap at the turn of the century:

Up to this time the water supply of the city has been turbid during one third of the year, at times so much so as to render the water absolutely unfit for either drinking, laundry or bathing purposes.”[5]

D.C. authorities blamed the problem on towns upriver, as far away as Cumberland, Maryland, dumping refuse into the Potomac watershed. The War Department (in charge of the District water supply since a time before any D.C. government existed) insisted that the Potomac River was in fact much cleaner than those in other cities,[6] even though bacteria from human fecal matter was found in the river in large quantities.[7]

Typhoid death tolls kept rising, and the city was faced with a crisis. In 1901, the Senate District Committee, headed by Senator James McMillan of Michigan (namesake of the McMillan Plan to develop Washington’s monumental core and remake the National Mall) met at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel in New York City to listen to experts and resolve the problem. Over the course of the hearing, it became clear that widescale water filtration would be necessary.[8]

But until a plant could be built, all Washingtonians could do was boil their water and bide their time, as The Washington Post lamented in 1900:

From present indications there is no relief for the city inside of from three to four years. A filtration plant, the one thing that will prevent the wholesale contraction of typhoid, is to be constructed in the vicinity of the Soldiers’ Home. The foundations are now being built, but it is estimated that it will not be completed before the later part of 1903 or the early part of 1904.” [9]

The McMillan Sand Filtration Plant was actually not fully finished until late in 1905, a record-breaking year for typhoid.[10] Once the plant was done, the raw water supply of the District (whose residents then used about 60,000,000 gallons of water per day) could be fully replaced with filtered water.[11]

Yet in early August 1905, with typhoid season about to reach its peak, the opening of the not-yet-completed plant was too urgent to be delayed any longer. Washingtonians begged the city to "rush the work as rapidly as possible”— to continue around the clock if necessary— but engineers argued that a hasty job might be dangerous and explained that "owing to the character of the work … it cannot be pushed at night.”[12]

D.C. Commissioner Henry MacFarland found a way for the plant to ease into operation, suggesting that each filter bed be put into service as soon as it was completed. With progressively more and more clean water entering the water supply as time went on, the dirty water would be diluted. MacFarland offered an explanation that any barfly could appreciate:

It is on the same principle that the addition of water to whisky reduces the harmful effect of the liquor in just the proportion of its dilution. It is obvious that a man swallowing a drink of half whisky and half water would imbibe exactly 50 per cent of the alcohol taken by the man who swallows his whisky ‘straight.’”[13]

As the first few filtration beds were completed, 3,000,000 gallons of pure water per day per bed were flowing into the District's water mains. Still, MacFarland urged residents to boil their water until the entire plant was finished, citing a then well-known rule that the typhoid germ usually takes three weeks to gestate.

About three weeks after the first filter bed opened, the Evening Star proclaimed the success of the plant.

With this well-established rule as a basis it seems that at least a portion of the decrease in the fever in Washington should be attributed to the filtration of a part of the water supply, while probably another portion of the credit should be given to the public, who, doubtless, have heeded the many warnings to boil all drinking water or to otherwise take precautions against possible infection.”[14]

For a while this optimism dominated the headlines, but a few weeks later:

Much comment is being heard these days concerning the possible effect or lack of effect the filtration of a part of the city’s water supply within the past six weeks has had upon the spread of typhoid fever. The general opinion seems to be that the experiment has not proven to be a marked success.”[15]

Critics believed any benefits of filtration were nullified by the fact that no one had cleaned the grimy pipes and mains before the purified water was released. New cases of typhoid were as widely reported as ever,[16] and on top of that, the process to clean the filter ended up spilling mud into the city sewer system.[17]

So, the immediate legacy of the McMillan Sand Filtration Plant was rather shaky. The death rate in Washington didn’t drop much at first. Fortunately, however, the picture improved in the coming years. Typhoid in the District, while not eradicated, was significantly reduced.[18]

As time passed and demand for water in D.C. grew, the McMillan plant became too small to meet the city’s needs. New plants with more modern technologies were built to accompany and eventually replace it. The plant remained in operation until 1986, and five years later it was named a D.C. Historic Landmark.[19]

Now that it’s not working to quell a typhoid epidemic, the plant and the land surrounding it are currently proposed for another purpose—commercial and residential development. But preservationists, notably the Friends of McMillan Park, have appealed to preserve the site.[20]

Footnotes

- ^ “At the Filtration Plant.” Evening Star, April 09, 1905: 59, accessed June 14, 2019, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/image/v2:13D5DA85AE05A305…@?p=WORLDNEWS.

- ^ "Epidemic of Typhoid: Impure Water Supply is the Cause of the Disease." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Dec 05, 1900. https://library.access.arlingtonva.us/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/docview/144168024?accountid=57895, and “All Records Broken: Typhoid Fever Makes a Rapid Gain.” Evening Star, August 15, 1905: 1, accessed June 14, 2019, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/image/v2:13D5DA85AE05A305…@?p=WORLDNEWS.

- ^ "Epidemic of Typhoid: Impure Water Supply is the Cause of the Disease." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Dec 05, 1900.

- ^ "Light on City Water: F.W. Albert Tells about District's Great Supply." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Feb 08, 1914. https://library.access.arlingtonva.us/login?url=https://search-proquest….

- ^ "Fever Spreads Apace: Thirty-nine Cases of Typhoid Reported Yesterday." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Aug 15, 1905. https://library.access.arlingtonva.us/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/docview/144610926?accountid=57895.

- ^ “Potomac Not Polluted: War Department Disapproves of Scheme to Obtain Pure Water Supply.” Evening Star, February 15, 1905: 1, accessed June 14, 2019.

- ^ "Epidemic of Typhoid: Impure Water Supply is the Cause of the Disease." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Dec 05, 1900.

- ^ ”Filtering of Water: Senate District Committee Holds a Hearing in New York.” Evening Star, January 05, 1901: 8, accessed June 19, 2019, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/image/v2:13D5DA85AE05A305…@?p=WORLDNEWS.

- ^ "Epidemic of Typhoid: Impure Water Supply is the Cause of the Disease." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Dec 05, 1900.

- ^ “All Records Broken: Typhoid Fever Makes a Rapid Gain.” Evening Star, August 15, 1905: 1.

- ^ “Filtered Water Only: Mains to Supply Nothing but Pure Drink after October 1.” Evening Star, September 26, 1905: 5, accessed June 14, 2019, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/image/v2:13D5DA85AE05A305…@?p=WORLDNEWS.

- ^ “Not Rushing Work: Typhoid Does Not Affect Filtration Plant.” Evening Star, August 09, 1905: 2, accessed June 14, 2019, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/image/v2:13D5DA85AE05A305…@?p=WORLDNEWS.

- ^ “All Records Broken: Typhoid Fever Makes a Rapid Gain.” Evening Star, August 15, 1905: 1.

- ^ ”Fever on the Wane.” Evening Star, September 12, 1905: 2, accessed June 14, 2019, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/image/v2:13D5DA85AE05A305…@?p=WORLDNEWS.

- ^ ”Comment is Adverse: Mixing of Filtered Water with Old Supply.” Evening Star, September 27, 1905: 7. accessed June 14, 2019, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/image/v2:13D5DA85AE05A305…@?p=WORLDNEWS.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ "Scenes from the Past...," The InTowner, November 01, 2004: 012, accessed June 14, 2019, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/1195CD2F2D3AACA0?p=WORLDNEWS.

- ^ Gaub, John. "Some Relations between the Water Supply and Typhoid Fever in Washington, D.C." Journal (American Water Works Association) 1, no. 4 (1914): 727-33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41225023, and "Scenes from the Past...," The InTowner, November 01, 2004: 012.

- ^ "Scenes from the Past...," The InTowner, November 01, 2004: 012.

- ^ Koma, Alex. ”McMillan redevelopment scores more time to let court challenge play out.” Washington Business Journal. May 3, 2019. https://www.bizjournals.com/washington/news/2019/05/03/mcmillan-redevel…;

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)