L'Enfant's Funeral: An Honor 84 Years Overdue

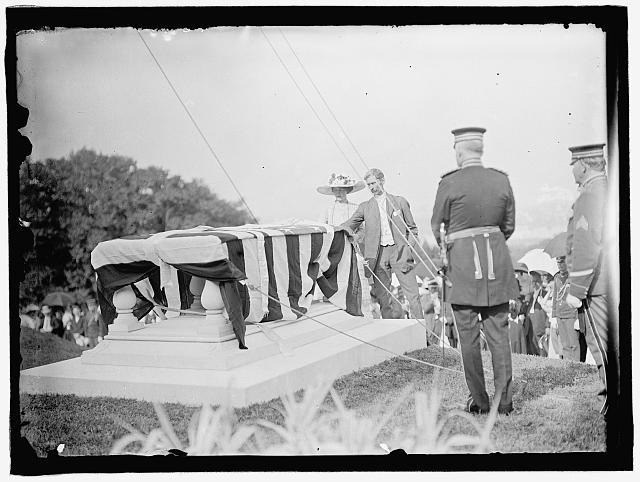

L'Enfant's second burial drew a large crowd to the portico of the old Lee mansion in 1909. (Source: Library of Congress)

At noon on April 28, 1909, a funeral procession nearly a mile long paraded down Pennsylvania Avenue and M Street, complete with fine carriages and a military escort. Throughout Washington, D.C., flags were displayed at half mast, spectators lined the streets, and school children were allowed a break from their studies to glimpse out the window and see it pass by.[1]

The cortège was coming from the Capitol rotunda, where Washingtonians had paid their respects to the man in the flag-draped casket before he was buried at Arlington Cemetery. Up to that point, the only other people who had the honor to lie in the rotunda were Abraham Lincoln, Thaddeus Stevens, Salmon P. Chase, Charles Sumner, James A. Garfield, John A. Logan, and William McKinley.[2]

And the man receiving that honor now was a hero of the American Revolution, the brilliant engineer who laid out many of the plans for the Nation’s Capital as we know it today —Major Pierre Charles L’Enfant… who died in 1825.

The pomp and circumstance of L’Enfant’s burial came 84 years late, so where had he been during all that time?

On a farm in Prince George’s County, Maryland, as it turns out. His body lay in an unmarked grave on the “Green Hill” estate, which belonged to his friend William Dudley Digges.[3]

To make up for all those lost years, several Supreme Court Justices, President Taft, Vice President Sherman, and French Ambassador Jusserand were all present at the ceremonies of 1909. A few of these men tried to explain the tardiness of the honor. The Vice President lauded L’Enfant’s skill in designing the District:

These plans, which are now universally praised, were laughed at, derided and set aside as being too expensive and too ambitious at the time they were made; but it is to L 'Enfant 's adherence to his original idea and his belief in the future greatness of this country, that the beauty of this city is due."[4]

Ambassador Jusserand added, “What followed for the city and him is known to all: while the city slowly grew, his own fortunes dwindled."[5]

And so, nobody paid much attention to L’Enfant until around the centennial of Washington, D.C., in 1900. A L’Enfant club was formed in 1892,[6] and in the early twentieth century there were movements for memorials and statues to be dedicated to the engineer.[7]

In 1904, Dr. James Dudley Morgan, ancestor of William Dudley Digges, lobbied to mark L’Enfant’s grave at Green Hill and perhaps create a fitting monument to him in Washington:

It is a fact of family tradition that many of his days at Green Hill were passed in laying out a miniature garden with walks and boulevards radiating like the streets and avenues of our Federal city… Congress might be satisfied to erect a monument to his memory in the city of Washington, and leave his dust to rest undisturbed where he passed the last years of his sad life.”[8]

That was the plan, until city commissioners realized that the current owners of Green Hill, the Riggs family, would not consent to permanently donate a part of their land[9] or provide a right of way to visitors of L’Enfant’s tomb.[10]

So L’Enfant’s remains would go to a new home. The Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul (the Episcopal Washington National Cathedral) offered to take them.[11] But perhaps because L’Enfant was a Catholic, in 1908, with the approval of the Riggs family, it was determined that he would be reinterred in the fall of that year on the grounds of the Catholic University of America.[12]

Exactly what went on behind the scenes to change the site and date of L’Enfant’s burial is unclear, but it might have had something to do with his military service. In December of 1908, when D.C. Commissioners announced plans to bury him at Arlington, Commissioner Henry MacFarland apologized for the delay, telling the Evening Star that he had “learned from the War Department that the remains could be properly interred as those of a soldier of the nation. The place seemed appropriate because it is a national cemetery, belongs to the United States and overlooks the city of Washington.”[13]

With respect to religion, Father William T. Russell of Saint Patrick’s Church, where L’Enfant had been a parishioner, was to consecrate the ground and preside over the ceremony at Arlington.[14]

And so, on April 22, 1909, a small group set out to the unmarked grave at Green Hill to dig up the now-famous engineer. Dr. Morgan described the scene vividly:

The tall, slender tree which marked the spot where the Franco-American lay, and which had been planted at the head of the grave at the time the body was buried, June 14, 1825, had first to be carefully cut down before the work of transferring the body to a hermetically sealed casket could be begun. A thunder storm interrupted the operations for twenty minutes after the ground had been broken, then the digging of the grave was continued, in silence, for an hour or more… As the party stood with uncovered heads around the excavation, the transfer of the remains of the famous engineer was begun. A cardinal bird, sitting in a near-by tree, sang almost continuously during the work at the grave.”[15]

According to The Washington Post, “discolored mold 3 inches in thickness, two pieces of bones, and a tooth were all that remained of the engineer,” but these were collected and stored in a vault at Mt. Olivet Cemetery, awaiting the day of the funeral six days later.[16]

The funeral itself was a grand one. By the time the procession made its way to Arlington, hundreds were gathered on the hill just in front of Mary Custis Lee’s (wife of Robert E. Lee) former mansion for a moment of silence, followed by three thundering volleys fired by the 15thCavalry of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. A lone bugler played taps, and then Father Russell stepped up to pray over the gravesite.[17]

The burial went so well that Ambassador Jusserand remarked, “This impressive ceremony today is more than enough to recompense for all that Maj. L’Enfant did for the country he loved so well.”[18] But this commemoration was by no means over.

Two years later, on May 22, 1911, hundreds of people again crowded the portico of Lee’s old mansion—this time to see L’Enfant’s grave marked as he deserved. Above the inscription on the new marble slab was an etching of L’Enfant’s original map of D.C.[19]

Some of the wood from the only headstone L’Enfant had known up to this point, the cedar tree that stood over his first grave at Green Hill, was fashioned into a cane and presented to a grateful President Taft about a month after L’Enfant’s new grave marker was unveiled.[20]

During the unveiling ceremony, overlooking the city of Washington, D.C., Taft expressed his deep respect for L’Enfant.

We are here to celebrate the last rites of the man who designed the plan, the execution of which has made Washington beautiful. There are not many who have to wait 100 years to receive the reward to which they are entitled until the world shall make the progress which enables it to pay the just reward … L’Enfant will now lie here appropriately in state and in rest, with the gratitude of the nation that he served so well.”[21]

Footnotes

- ^ “Burial of L’Enfant: Program for Ceremonies to Be Held Tomorrow.”Evening Star, April 27, 1909: 4, accessed June 18, 2019, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/image/v2:13D5DA85AE05A305@EANX-NB-142DD2C2F1628C30@2418424-142D808A12490F90@3-142D808A12490F90@?p=WORLDNEWS.

- ^ Morgan, James Dudely. “The Reinterment of Major Pierre Charles L’Enfant.” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C., Vol. 13 (1910), pp. 119-125,Historical Society of Washington, D.C. 125. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40067014.

- ^ Ibid., 118.

- ^ “Honor to L’Enfant Tardy but Sincere.” Evening Star, April 28, 1909: 1, accessed June 18, 2019, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/image/v2:13D5DA85AE05A305….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ "Relics of Maj. L'Enfant.: Meeting of the Club which will Perpetuate his Memory." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Aug 21, 1892. https://library.access.arlingtonva.us/login?url=https://search-proquest…;

- ^ Monument to Maj. L'Enfant." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Mar 29, 1904. https://library.access.arlingtonva.us/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/docview/144491354?accountid=57895. and"Will Move L'Enfant's Body.: Commissioners to Carry Out Action Authorized by Congress." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Dec 05, 1908. https://library.access.arlingtonva.us/login?url=https://search-proquest….

- ^ "Honors to L'Enfant: Monument in Washington and Stone over Grave." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Oct 01, 1904. https://library.access.arlingtonva.us/login?url=https://search-proquest….

- ^ The Riggs family would erect a cenotaph years later on the site of L'Enfant's original grave at Green Hill.

"E. Francis Riggs standing by stone slab which he had erected in honor of Pierre Charles L'Enfant." Photographic Print. Underwood & Underwood, July, 1925. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. https://lccn.loc.gov/2002714499. - ^ "Grave of Maj. L'Enfant.: Riggs Heirs Decline to Grant Space for Proposed Monument." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Apr 16, 1905. https://library.access.arlingtonva.us/login?url=https://search-proquest….

- ^ "Offers Grave for L'Enfant: Bishop Satterlee Tenders Site in Grounds of Cathedral." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Oct 14, 1904. https://library.access.arlingtonva.us/login?url=https://search-proquest….

- ^ "Will Move L'Enfant's Body.: District to have it Reinterred in Catholic University Campus." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Jul 18, 1908. https://library.access.arlingtonva.us/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/docview/144834985?accountid=57895. And “To Move L’Enfant’s Body: Catholic University Campus Site for Memorial” Evening Star, July 17, 1908: 2, accessed June 20, 2019, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/image/v2:13D5DA85AE05A305…@?p=WORLDNEWS.

- ^ “To Move L’Enfant’s Body: Will be taken from Digges Farm to Arlington.” Evening Star, December 04, 1908: 22, accessed June 20, 2019, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/image/v2:13D5DA85AE05A305…@?p=WORLDNEWS.

- ^ “Honor to L’Enfant Tardy but Sincere.” Evening Star, April 28, 1909: 1.

- ^ Morgan, James Dudely. “The Reinterment of Major Pierre Charles L’Enfant.” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C., Vol. 13 (1910), pp. 119-125,Historical Society of Washington, D.C. 120. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40067014.

- ^ "L'Enfant Disinterred." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Apr 23, 1909.

- ^ Morgan, James Dudely. “The Reinterment of Major Pierre Charles L’Enfant.” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C., Vol. 13 (1910), pp. 119-125,Historical Society of Washington, D.C. 123-124. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40067014.

- ^ “Honor to L’Enfant Tardy but Sincere.” Evening Star, April 28, 1909: 1.

- ^ "Honor to L'Enfant: Memorial to City's Designer Unveiled at Arlington." The Washington Post (1877-1922), May 23, 1911. https://library.access.arlingtonva.us/login?url=https://search-proquest….

- ^ "Historic Cane for President." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Jun 09, 1911. https://library.access.arlingtonva.us/login?url=https://search-proquest….

- ^ "Honor to L'Enfant: Memorial to City's Designer Unveiled at Arlington." The Washington Post (1877-1922), May 23, 1911.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)