When the Klan Descended on Washington

“Phantom-like hosts of the Ku Klux Klan spread their white robe over the most historic thoroughfare yesterday in one of the greatest demonstrations the city has ever seen.”[1] So read The Washington Post on the morning of August 9th, 1925. On the previous afternoon, the nation’s capital bore witness to the largest Klan march in the city’s history as tens of thousands of robed Klansmen marched down Pennsylvania Avenue towards the Washington monument, most of them feeling no need to wear a mask.

The 1920s were the gilded age for the Klan, as many successful and powerful people were either openly Klansmen or sympathetic to the cause. The organization boasted a membership of 4 million nationwide, including prominent community leaders from coast to coast.[2] Indeed, during this period, Klan membership was not something many members chose to keep secret. As historian Ibram X. Kendi has noted, “You had many members of the KKK who were politicians – senators, congressmen, statehouse representatives and that only encouraged members to appear publicly without their hoods.”[3]

This can be attributed, at least partially, to the way the Klan had tried to market itself. The first iteration of the KKK had come into existence after the Civil War and was associated with violent attacks on African Americans. After coming under fire during Reconstruction, it had collapsed by the 1870s. With the so-called second coming of the Klan in the 1910s and 1920s, the group tried to emphasize a nativist, American-first agenda. When Col. William Simmons announced the rebirth of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in 1915, he put out advertisements celebrating “The World’s Greatest Secret, Social, Patriotic, Fraternal, Beneficiary Order” and a “High Class Order for Men of Intelligence and Character.”[4] This sort of camaraderie, along with the nativist message, resonated with many white Protestants in an era that had seen the mass migration of African Americans from the South to the North and an influx of Jewish and Catholic immigrants from Europe.[5]

At least officially, there was an effort to distance the new KKK from the violence that defined its predecessor. As Simmons told the House Rules Committee in 1921, “The charge is made…. that we are organized to preach and teach religious intolerance and especially that we are anti-Roman Catholic and anti-Negro. The works of the Klan prove this absolutely untrue. Many alleged outrages have been attributed to the Klan, but none of these were against Roman Catholics, Jews, and negroes per se, and none were committed by the Klan.” He went further to claim that the Klan had never “taken the law into its own hands.”[6] Such statements were, of course, false. As much as ever, the Klan of the 1920s was a white supremacist organization that carried out innumerable acts of violence against African Americans, religious minorities, and others.

Against this backdrop, the days leading up to the parade were hectic, even by Washington, D.C. standards. Visitors poured into the nation’s capital for the event – thousands to participate and thousands more to watch. As The Sun noted, “Practically every state East of the Mississippi was represented” as the roads leading to D.C. turned into a parade of automobiles decorated with extravagant Klan signs and symbols.[7] One journalist observed, “one of the first groups to reach Washington came with a big fiery cross, emblazoned with tiny electric bulbs, attached to the radiator cap of their motor.”[8] Another observer stated, “scores of the cars in the public parking places set aside for the visitors were covered with signs indicating the ‘100 percent Americanism’ of their occupants.” Many of these “100 percent” Americans converged around tents after leaving their automobiles. In what was practically a campsite, many tents shared the same visual extravagance as the automobiles. “On the ridge pole of one tent was nailed a foot-high flaming cross, painted bright crimson.”[9]

While the KKK had plenty of local support, not everyone was happy with the influx. Thomas L. Avaunt roamed the streets in the days leading up to the march, distributing circulars and pleading with his fellow Washingtonians to “Arise and Stop this Farce With a Legal War.” His fliers, which provided the names and home addresses of local Klan leaders, read in part: “All Christian men and women bow their heads in shame when they know the streets of their city may soon be bathed in blood. Those of us who are Christians and believe in law and order cannot forget the scores of cities where similar parades of the KKK have been the cause of murder and bloodshed and without a minute’s notice men and women have been shot.”[10]

Rumors began to circulate that the African American community had been arming itself to combat the parade, buying up all the rifles and revolvers in local thrift shops. The Metropolitan Police investigated the claims and debunked them. In a public statement, they were adamant that no such violence was planned. In fact, in hopes of avoiding conflict, police and African American pastors urged their congregants to steer clear of the crowds gathering around the parade.[11]

In the weeks leading up to the event, it seemed likely the Klan would have a large presence, though organizers had hedged their bets, offering conservative estimates. But on the day before they took to the streets, that changed. According to The New York Herald, “Leaders of the Klan, abandoning the reserve and conservatism which had characterized their predictions regarding the demonstration, admitted tonight they expected at least 50,000 visitors and that the number might greatly exceed that. They also retracted recent declarations that only 5,000 would march in the parade, asserting that 20,000 or 30,000 might participate.” By the time the event kicked off in the blazing 3pm heat, the parade included an estimated 30,000 marchers and 150,000 spectators.[12]

The New York Herald captured the scene: “30,000 men and women, clad in the white robes and conical hoods of the Ku Klux Klan paraded down Pennsylvania Avenue today from the capitol to the treasury. It took nearly three and a half hours for the colorful procession to pass.”[13] The Chicago Daily Tribune noted there were mainly “large portions in which state and county delegations of the order trooped along in the plain robe and hoods,” but there were also, “kleagles, dragons, and other dignitaries of the organization in green silken robes and hoods, flaming red, bright, yellow and red, white and blue,” and “companies of Klans guards in snappy uniforms, white caps, black Sam Browne belts, and black puttees.”[14] Some press outlets noted the precision of the march but The Washington Post observed, “There were few drilled marchers in the parade. At times their lines, extending the full length of the Avenue, swayed hopelessly back and forth.”[15]

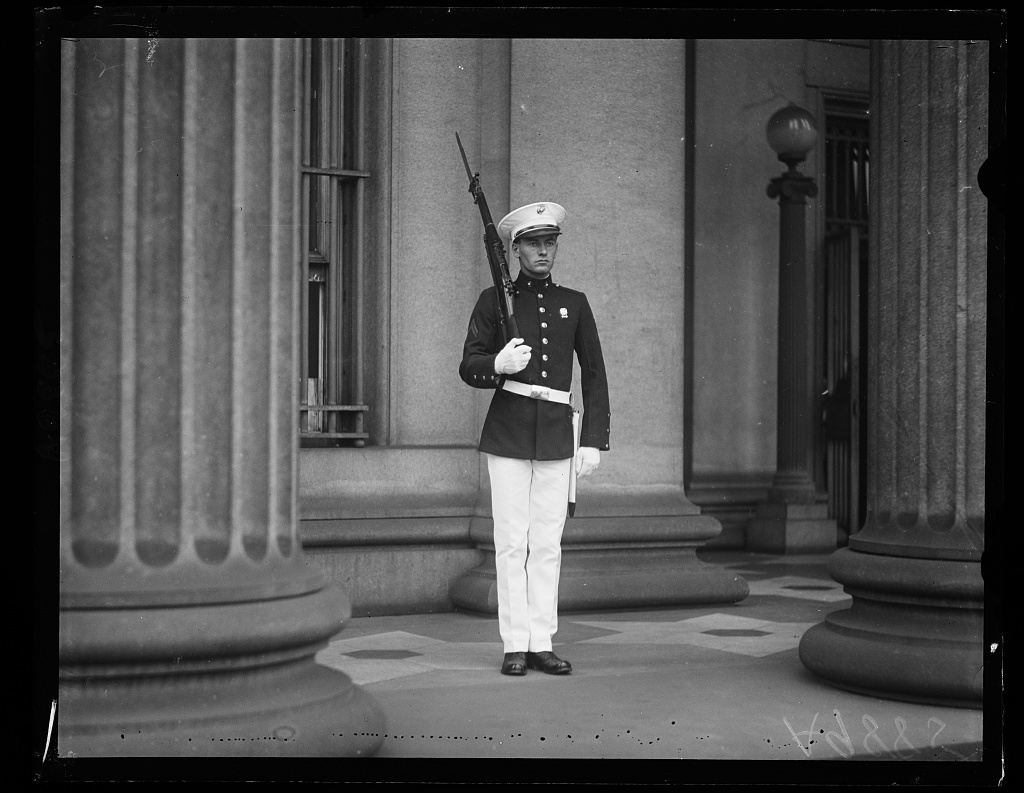

Organizers had prepped ahead of time to have first-aid stations for any who might suffer from heatstroke, and many needed aid. Meanwhile, the Federal government stationed Marines outside of several federal buildings along Pennsylvania Ave., explaining that the decision was in “accordance with a regulation which provides for marine guard on all public occasions of this character in Washington.”[16]

Beyond the pomp and circumstance, one of the markers of the parade was just how visible the “Invisible Empire” had made itself on the streets of Washington. Rather than hiding behind masks, the Klansmen had been ordered to have their faces exposed for the march in an effort to add legitimacy to the demonstration.[17]

When the procession finally concluded at the base of the Washington Monument at 7pm, one might say karma struck. There was to be a massive pageant where the “eloquence of Klan orators,” were to “have poured forth to stimulate and perhaps electrify the multitude.”[18] Instead, dark clouds gathered overhead.

District Dragon L.A. Mueller attempted to reassure the crowd, “I have faith enough in the Lord that He is with every Klansman,” he told the restless audience. “You ought to have as much faith in Him as I have. We have never had a drop of rain in Washington when we got on our knees.”[19] Right about then, the heavens opened up. As the crowd hurriedly dispersed, Mueller cried out for them to stick around long enough to hear the details of the following day’s events. “In half an hour the picture of the assembled Klansmen had dissolved from view.”[20]

Though the parade was over, the Klan’s demonstrations were not. The next evening, organizers had planned a cross burning at the Arlington Horse Showgrounds. Like the parade, that event was designed to convey power. As the Chicago Daily Tribune reported, “The cross will stand 80 feet above the ground, and the cross beam will be 30 feet wide.” It supposedly came from a giant tree in Virginian mountains and was left in the care of a heavy guard in Arlington County.[21]

An estimated 75,000 people attended what The Washington Post called “one of the strangest scenes of their lives.”[22] The paper continued, “In automobiles and afoot they moved warily from the main highway through a dark neck-like road that opened into the darkness of the grounds. Here ghost-like figures moved about in silhouette against the black background. Flashlights and the headlights of automobiles occasionally revealed the white-robed hosts out in all their splendor. In the wooden stand where prominent horsemen are wont to judge thoroughbred horses, sat L.A. Mueller, Grand Kleagle for the District Klan, and other officials of the order, a sole electric light playing on their multi colored uniforms. Before the stand was a small electrically lighted cross, and forming a wide circle around it were the mute figures of the Invisible Empire.”[23]

As 200 initiates stood by, “the cross, reared in another section of the field, was lighted and in turn threw the whole spectacle into vivid relief. A still wider circle of the hooded hosts formed around the cross, each figure standing behind an American flag planted in the ground. The notes of ‘Onward, Christian Soldiers’ lifted from the band, and then those of ‘America,’ as Klansmen, two abreast and bearing flags, marched into the circle that enveloped the stand.”[24] When the ceremony had ended, and the crowds headed back home, police Capt. Headley estimated traffic was “the heaviest since the burial of the Unknown Soldier” at Arlington National Cemetery four years prior.[25]

Though it was difficult to ascertain at the time, August of 1925 probably marked the peak of the Klan’s popularity. Despite the group’s best efforts to reach new followers, the “greatest un-masked demonstration ever staged by the secret order” was not matched in subsequent years. By the end of the decade, membership in the Invisible Empire had dropped off considerably, before another surge during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.[26]

Footnotes

- ^ McArdle, Terence, “The day 30,000 white supremacists in KKK robes marched in the nation’s capital,” The Washington Post, August 11, 2018 https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2017/08/17/the-day-30000-white-supremacists-in-kkk-robes-marched-in-the-nations-capital/

- ^ “Ku Klux Klan,” Southern Poverty Law Center, 2018, https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/ideology/ku-klux-klan

- ^ McArdle, Terence, “The day 30,000 white supremacists in KKK robes marched in the nation’s capital”

- ^ Rothman, Joshua, ”When Bigotry Paraded Through the Streets,” The Atlantic, December 6, 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/12/second-klan/509468/

- ^ Rothman, “When Bigotry Paraded Through the Streets”

- ^ “Wizard Says Klan Isn’t Anti Anything,” The New York Herald, October 12, 1921, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045774/1921-10-13/ed-1/seq-13/#date1=1789&index=12&rows=20&words=K.K.K+PARADE&searchType=basic&sequence=0&state=&date2=1963&proxtext=kkk+parade&y=0&x=0&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=1

- ^ Essary, J.F., “35,000 in Klan Garb Parade in Washington,” The Sun, August 9, 1925

- ^ “Klan Paraders Swarm to Capital as Marines Guard U.S. Buildings,” The New York Herald, August 8, 1925

- ^ Essary, “35,000 in Klan Garb Parade in Washington”

- ^ “Klan Paraders Swarm to Capital as Marines Guard U.S. Buildings,” 1925

- ^ “Klan Paraders Swarm to Capital as Marines Guard U.S. Buildings,” 1925

- ^ “Klan Paraders Swarm to Capital as Marines Guard U.S. Buildings,” 1925

- ^ “Klan Paraders Swarm to Capital as Marines Guard U.S. Buildings,” 1925

- ^ “Klan Parades Capital; Peace Rules March,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 9, 1925

- ^ McArdle, “The day 30,000 white supremacists in KKK robes marched in the nation’s capital”

- ^ “Klan Paraders Swarm to Capital as Marines Guard U.S. Buildings,” 1925

- ^ McArdle, Terence, “The day 30,000 white supremacists in KKK robes marched in the nation’s capital”

- ^ Essary, “35,000 in Klan Garb Parade in Washington”

- ^ Essary, “35,000 in Klan Garb Parade in Washington”

- ^ Essary, “35,000 in Klan Garb Parade in Washington”

- ^ “Klan Parades Capital; Peace Rules March,” 1925

- ^ “Klansmen Display Huge Fiery Cross in Weird Pageant,” The Washington Post, August 10, 1925

- ^ “Klansmen Display Huge Fiery Cross in Weird Pageant,” 1925

- ^ “Klansmen Display Huge Fiery Cross in Weird Pageant,” 1925

- ^ “Klansmen Display Huge Fiery Cross in Weird Pageant,” 1925

- ^ McArdle, Terence, “The day 30,000 white supremacists in KKK robes marched in the nation’s capital”

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)