The D.C. Nine: The Clergy Who Committed Crimes to Protest Napalm

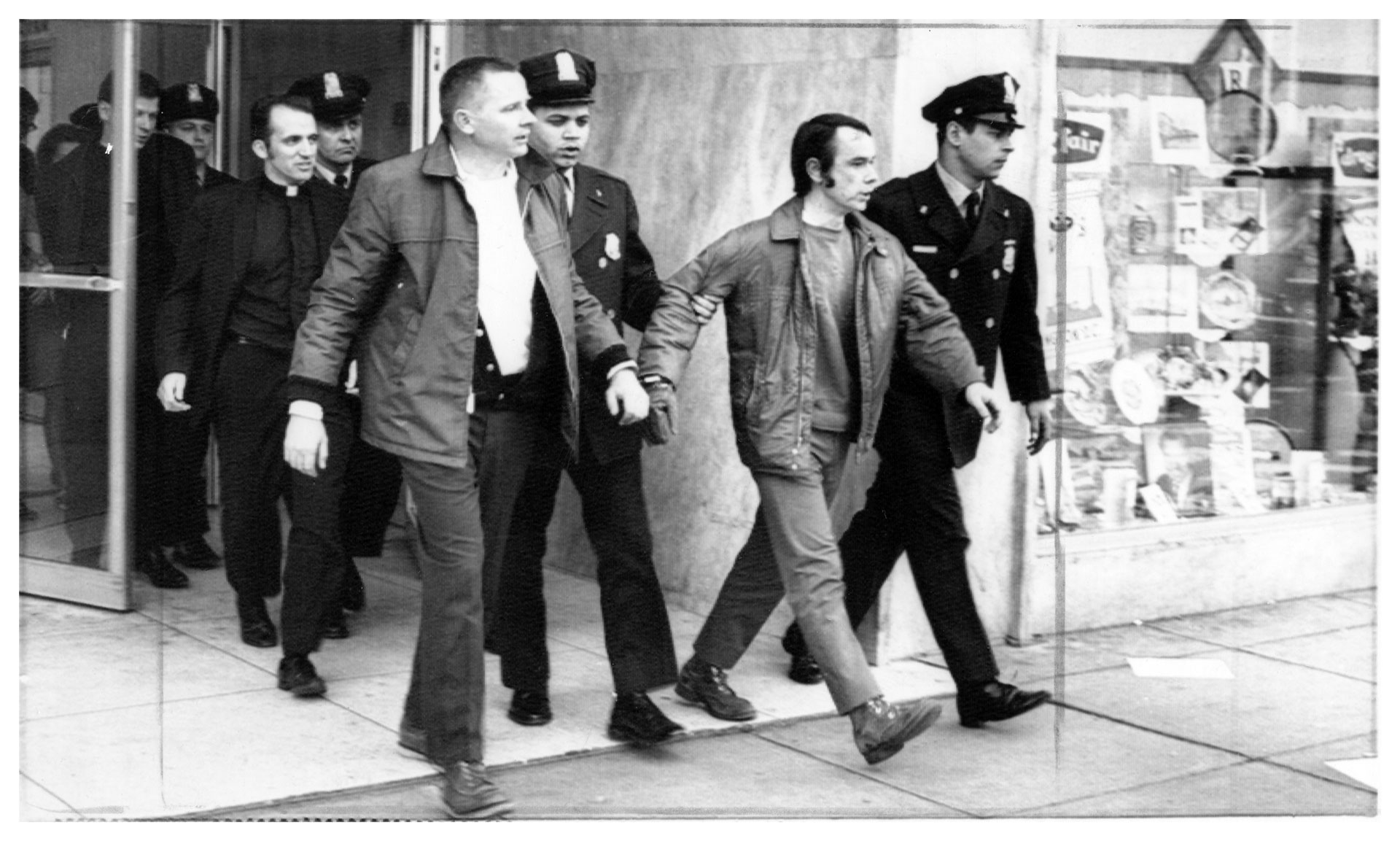

Denny Maloney, Arthur Melville, Bernie Meyers and Bob Begin. (Source: Washington Area Spark)

"Nine persons broke into the Washington offices of Dow Chemical Co. at 15th and L Streets nw. yesterday, poured what they said was human blood on furniture and equipment and threw files out a fourth floor window,” read the front page of the Washington Post on Sunday, March 23, 1969.[1] The images which accompanied the article showed a chaotic scene: one protestor heaving files out of a broken window; papers scattered, as if struck by a tornado, across the pavement below. “There was little conversation and much noise as the demonstrators did their work,” wrote another journalist, “Police arrived about 10 minutes after the ruckus started. The nine surrendered peacefully, and sang the ‘Battle Hymn of the Republic’ as they were led into police vans.”[2]

If the protest was striking because of the tactics the protestors employed, it was all the more-so because of the composition of the group. As they were led in handcuffs out of the building, it became clear that these were no ordinary hippies. Even by the eccentric standards of the late ‘60s, the demonstrators were dressed oddly, wearing not flowered shirts and bell-bottoms but clerical collars and black button-ups. But these were no costumes — eight of the nine who were arrested were Roman Catholic priests, nuns, and seminarians, in various stages of communion with the Church. But their Catholicism was not incidental to their protest: it was the cause of their protest.

In the months that followed, the group would come to be known as “The D.C. 9,” though they came from all over the country:

- Rev. Robert T. Begin, 30, a priest from Cleveland, Ohio

- Rev. Dennis J. Maloney, 28, a priest from Detroit, Michigan

- Sister Joann Malone, 28, a Catholic schoolteacher from St. Louis, Missouri

- Michael Slaski, 20, a draft-resister of Detroit, Michigian,

- Rev. Bernard Meyer, 31, a priest of Cleveland, Ohio

- Rev. Arthur G. Melville, 36, a former priest of San Francisco, California

- Catherine Melville, 32, a former nun, of Girard, Ohio

- Rev. Joseph F. O’Rourke, 30, a Jesuit in formation, of Woodstock, Maryland

- Rev. Michael R. Dougherty, 34, who had served as a U.S. Army paratrooper, of Hamburg, New York

The Catholic Left

These men and women were part of an emerging movement on the Catholic Left which was popularly associated with priests Daniel and Phillip Berrigan. Inspired by the tradition of Dorothy Day and the Catholic Workers movement of the 1920s, and encouraged by the democratizing reforms of the Second Vatican Council, as well as radical traditions external to the Catholic faith, the Berrigans and their compatriots were frustrated by the apathy of the American Catholic hierarchy and the broader Catholic populace with regards to the war in Vietnam.[3] As Begin shared in an interview, “I really was extremely embarrassed for the Church not being a leader. I mean, we weren't a leader in the racism fight, in the civil rights, we weren't the leader of women's suffrage. We weren't a leader in anything as a Catholic Church.”

To press the issue, this new generation of Catholic activists undertook demonstrations which pushed the limits of “non-violent protest.” The most famous of these was “Catonsville Nine” action, where a group of priests and laypeople led by the Berrigan brothers broke into a draft office in Catonsville, Maryland and burned draft cards with homemade napalm in 1968. But Catonsville was not the only demonstration. In January 1969, Father Robert Begin and Father Bernard Meyer were arrested for holding a “non-scheduled anti-war Mass” in the Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist in their home diocese of Cleveland.[4] A few weeks later they and others set their sights on Washington.

These actions were organized in a series of secretive retreats held across the country, which offered Catholics opposed to the Vietnam War the opportunity to debate ideologies of non-violence and organize actions to resist the war. The D.C. 9 action was no different. Invites were given via word of mouth: Michael Slaski, for example, recalled being informed of the budding D.C. 9 action by Denny Maloney.[5]Said Joann Malone, “who was going to participate, and which action, was sort of fluid.”[6]Slaski concurred, “It was just like, bang, bang, bang. We decided to do it and we did it. I don't remember being more than a week in Washington…This was all very anarchistic.”[7]

The Protest

Despite the absence of any detailed planning, they had a rough sketch of how the evening would go. The evening of March 22, Bernie Meyers gathered a group of photographers and journalists, who he had called in advance, and led them to a location in the Washington Post building, where they could witness the break-in across the street at the Dow Chemical offices.[8]Meanwhile, the others entered the building and made their way to the Dow office on the fourth floor. As Malone recalled recently, the mood was light: “We were not experts in any way, shape or form, at what we were doing, so there was laughter because it's like, how do we get the door open? I brought a crowbar, right? I hope it works.”[9] It worked; they broke in, and Joann and Catherine set to work finding files that related to Dow’s role in the U.S war effort (more on this later). They threw those files out the window, where they were collected and published by supporters who had gathered on the street, and eventually by the Washington Post. Meanwhile, the others vandalized the Dow office until the police arrived.

But why Dow Chemical? After all, many war resisters had targeted draft boards for acts of vandalism — why target a private corporation? The 9 outlined their motives in a statement entitled “An Open Letter to the Corporations of America,” which was distributed to the gathered press at the time of the break in.

“Today, March 22nd, 1969, in the Washington office of the Dow Chemical Company, we spilled human blood and destroyed files and office equipment,” began the page-long statement. The protestors then attacked the role of corporations in the United States war effort in Vietnam:

We are outraged by the death-dealing exploitation of people of the Third World, and of all the poor and powerless who are victimized by your profit seeking ventures. Considering it our responsibility to respond, we deny the right of your faceless and inhuman corporations to exist…You, corporations, who under the cover of stockholder and executive anonymity, exploit, deprive, dehumanize and kill in search of profit…In your mad pursuit of profit, you, and others like you, are causing the psychological and physical destruction of mankind. We urge you all to join us as we say no to this madness.[10]

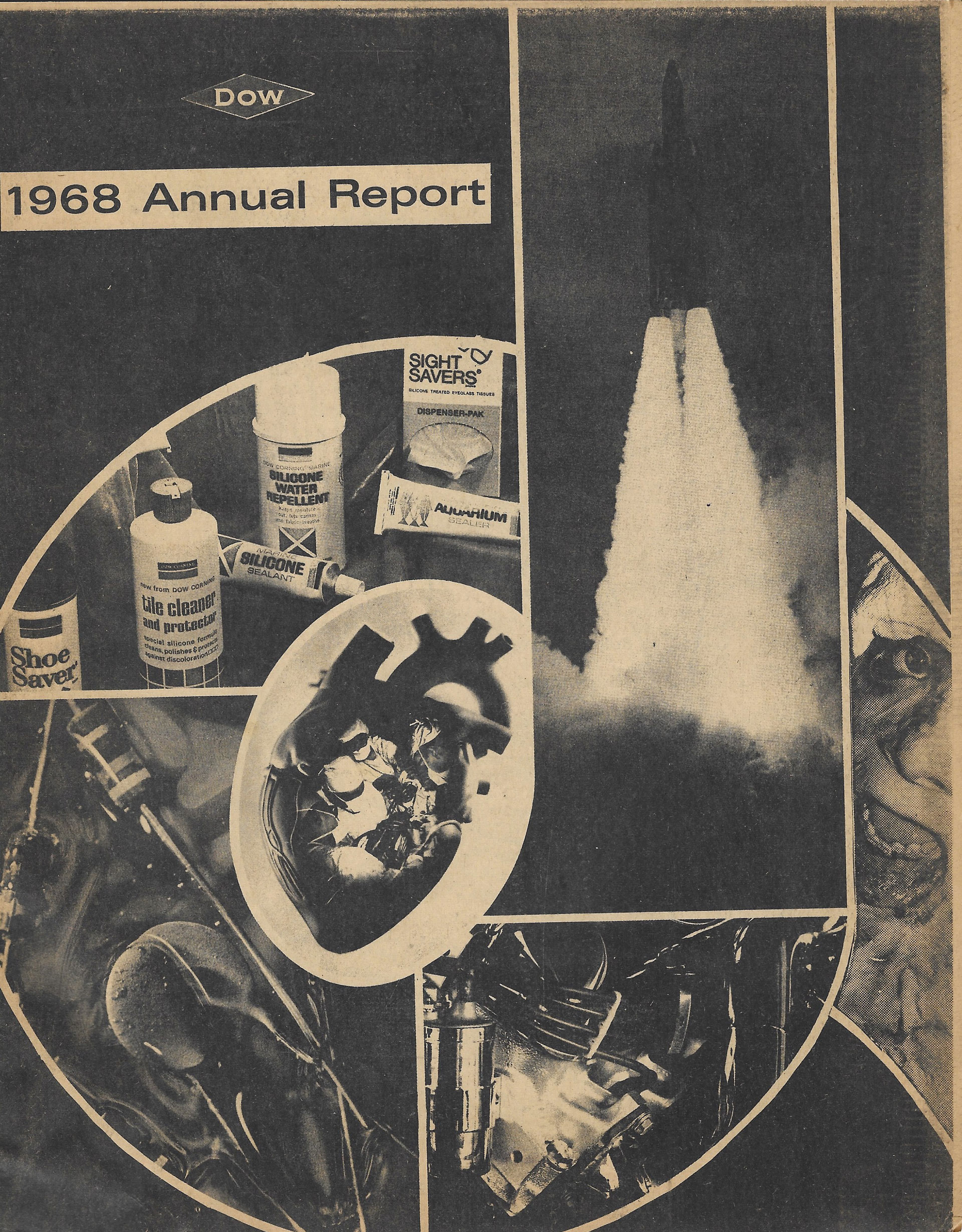

Dow Chemical, in particular, had been selected as the target because of its role in the “production of napalm, defoliants, nerve gas.’”[11] Begin described Dow’s role in the war in stark terms: “They were profiting so much. They made the napalm, they made the black bags that people came home in, and they made the defoliants. They were so involved in this war as a profit-making venture.”[12]

But, as it turned out, the D.C. 9 was intending to target a draft board too, according to Joann Malone. “There was supposed to be another action attached to ours to show the link between the draft board actions and Dow Chemical's…. There were 15 other people ready to go, to go into the D.C. draft board and take all their files.”[13] The draft board protest, which was more typical of other Catholic Left actions like Catonsville, had been planned alongside the Dow break-in. Unfortunately for the would-be demonstrators, somebody had let the FBI know they were coming: “When the other group got to the draft board to take files out the FBI was there, they were moving the files actually out of that building,” recalled Begin.[14] “We figured that there was some kind of infiltration in the group,” Malone added, “which was probably not that hard to do.”[15]

While the evening fell short of what the organizers had envisioned, the break-in at Dow Chemical alone achieved its desired effect: it could not be ignored. Anti-war protestors rallied to their cause, gathering outside the jails where they were being held to express support. When members of the D.C. 9 went on a hunger strike inside the jail to raise awareness of their action, protestors outside the jails joined them.[16]

The Trial

The attention and controversy only grew as the trial date approached. Scheduled for February 3, 1970, the trial was to be held in the D.C. District Court. The high-profile nature of the case initially worked in their favor — the D.C. 9 received representation from “fabulous, fabulous lawyers,” in the words of Malone.[17]Edward Bennett-Williams, one of D.C.’s most famous criminal defense lawyers, and a part owner of the Washington Redskins, represented Bob Begin, though to this day Begin has little idea how he came to be represented by such a high-powered attorney.[18] The others were represented by Addison Bowman, who was then affiliated with Georgetown Law Center, and by Phil Hirschkop, a veteran of civil rights cases who had a history of representing the D.C. anti-war movement. Hirschkop had also won the landmark decision Loving v. Virginia before the U.S. Supreme Court only two years earlier.

Even with their high-powered legal team, escaping punishment in court would be a tough task. As Phil Hirschkop recalled with a chuckle, “We couldn’t win on the facts…they’d called the press when they did the action. They’re all on tape and video.”[19]Not to mention that they had distributed a signed statement detailing and justifying their actions.

The timing of the case didn’t make it any easier. The D.C. case came on the heels of several high-profile trials of political activists which had been characterized by unrest, and at times, outright anarchy. Indeed, the trial of the Catonsville 9 demonstrators was so dramatic that it was subsequently turned into an off-Broadway play. Similarly, the trial of the so called “Chicago Seven,” a group of left-wing activists that had been arrested for the disorderly protest of the 1968 Democratic National Convention, had gotten so out of hand that the judge ordered one of the defendants, Black Panther Bobby Seale, to be bound and gagged in the courtroom.[20]

The presiding judge in D.C. 9 case, John Pratt, appeared determined to avoid the disorder of the Catonsville and Chicago trials. A devout Catholic and an ex-marine who had lost an arm in World War II, Pratt had a reputation for being hard on protestors and civil rights activists. “I knew that he was the last judge in that courthouse we wanted on this trial,” recalled Phil Hirschkop.[21]

Pratt made it clear to the jurors that he had no desire to engage with the broader political questions of the case:

Ladies and gentlemen, you are not trying the Vietnam War. The Vietnam War is not an issue in this case. You are not trying ideas. You are not trying the United States. You are not trying society. You are not trying any individual, any corporation, large or small. For there can be no freedom, no equal opportunity in an environment of criminal behavior. No nation should tolerate disregard of the law.[22]

But, of course, the D.C. 9 had every intention of making the case about the Vietnam war: “We wanted to use the trial to put Dow Chemical on trial” said Begin of their plans for the case. As Malone explained:

We knew that we wanted to talk about the war and about Dow Chemical's involvement. That was the purpose for the action: To be a voice, to tell the American public or whoever would listen what was going on in Vietnam… the vastness of the suffering, the number of people being killed, children maimed with napalm and the American troops that were suffering from Agent Orange.[23]

Speaking out against Dow’s policies during the trial went beyond raising public awareness. It was also the basis for the D.C. 9’s longshot legal strategy which they hoped would allow them to avoid prison — a little known legal concept known as jury nullification. Which is… what exactly? In short, jury nullification is the right of a jury to accept that the defendents committed a crime but refuse to convict them for it. As Phil Hirschkop put it, the goal was to “see if we get the jury to say, notwithstanding these facts, we think they put their ass on the line. They are trying to do something very valuable…for society and we're not going to punish them.”[24]

For the D.C. 9, having their voices heard — not simply speaking through their lawyers — was crucial to the jury nullification strategy. And so, they petitioned the court to fire their lawyers and represent themselves. According to Hirschkop, this was intended to allow them to more effectively plead their case directly to the jury.[25] Judge Pratt, fearing the disorder of Catonsville, denied their request and forced them to retain counsel. The defendants were outraged. Hirschkop took Pratt to task in open court, accusing him of keeping the defense lawyers around to facilitate speedy convictions: “’You’ve already made your mind about everything in the case except the length of the sentence... You are just sending these people packing off to jail as quickly as possible.”’ Art Melville suggested Pratt was “trying to frustrate the defense,” while Joann Malone was even more strident in her criticism: “If you’re more concerned about disruption of the proceedings than you are about justice, I don’t understand why you’re a judge.”[26] Not allowing to the defendants to represent themselves, she claimed, would turn the trial into a “farce… a game with the judge speaking to some lawyers.”[27]

The proceedings had a ritualistic quality to them, with the defendants repeatedly attempting to discuss the Vietnam War and the judge repeatedly denying them that opportunity in no uncertain terms. This back-and-forth was occasionally punctuated by a protestor in the gallery loudly expressing disgust and being promptly ejected from the courtroom.

By the third day of the trial, things boiled over: “A fist-swinging, shouting melee erupted among spectators, defendants, deputy marshals and special policeman…At least five persons, including two women, were thrown bodily out of the door of the courtroom, over screams of ‘let me go’ and ‘pig.’”[28]The inciting incident was an attempt by Sister Joann to discuss “Dow’s manufacture of weapons in Vietnam,” to which Pratt responded once again, “’the Vietnam war is not an issue in this trial.’” This so frustrated two spectators that they began to berate the judge, prompting marshals to attempt to toss them from the room. As more spectators joined the fray, one of the defendants, Michael Slaski, “jumped from his chair, hurdled several rows of seats and spectators, and plunged into the fracas.”[29] Hirschkop recalled being asked by the Chief Marshal to tame the chaos in the courtroom:

The judge ran off the bench. I stood up first on either a chair or the bench and there were bunch people in front of me. So I had to get up higher, so I stood up on the counsel table and I yelled at everyone "just please sit down, sit down.”[30]

Unsurprisingly, the courtroom theatrics left little room for the D.C. 9 to attempt a cogent legal defense. At the conclusion of the trial, Thomas Lippman, writing for the National Catholic Reporter compared them to “tennis players who stumbled by accident into a football scrimmage”: “At their own game they might be champions, but they were playing in the wrong ballpark.” It surprised no one, then, when “it took the jury less than an hour to find them guilty.”[31] “There is no place for violence in a society dedicated to liberty under the law” declared Judge Pratt.[32] Even Phil Hirschkop faced 30 days in jail at the end of the chaotic trial, for what Pratt alleged was “’conduct which offended the dignity and decorum’” of the court.[33] Hirschkop expressed his desire to fight the contempt, defense attorney Addison Bowman promised to appeal, and outside the courthouse on Constitution Avenue, protestors sang “We Shall Overcome.”[34]

Two months later, at the comparatively tranquil sentencing hearing where only one spectator was physically thrown from the courtroom, the D.C. 9 all received jail time. Catherine Melville and the Rev. Bernard Meyer, both of whom had pled “no contest” earlier in the trial, received the lightest sentences of 6-to-18 months in jail, most of which was suspended, leaving them facing about three months in jail, plus probation. As for the others, Malone suggested that “our sentences were given according to how obnoxious we were in the courtroom.”[35] Arthur Melville received the longest, a six-year sentence, and Malone herself received four. The D.C. 9, however, were unbowed: at a press conference held the day of the sentencing, they vowed “further and stronger resistance to the crimes of America…. In revolution, one wins or dies — we shall win. Power to the People.”[36]

And win they did, in the end. On June 31, 1972, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia ruled 2-1 to overturn the convictions of the seven members of the D.C. 9 who had pled not guilty to the charges, citing Judge Pratt’s decision to refuse their right to represent themselves.[37] Ultimately, only Bernie Meyers and Catherine Melville served jail time.

Meanwhile, Phil Hirschkop fought hard against his contempt charge, which was also reversed on appeal. The striking thing, however, was not the contempt hearing itself, but the judicial misconduct which Hirschkop claimed was revealed to him in the course of the appeal. According to Hirschkop’s sources, law enforcement had either infiltrated or wiretapped the house where the defendants were staying during the trial and “[Judge Pratt] was either told or played recordings of conversations I had with my clients at night.” The judge may have overheard some of the defendants’ uncharitable remarks about his metal prothesis — “they were making jokes about [how] he was being so damn harsh in court… that he was “ruling with an iron hand,” recalled Hirschkop — which further poisoned the judge against the attorneys.[38] Hirschkop called the surveillance meetings “grossly improper” and argued that the judge “engaged in serious misconduct.”[39] Judge Pratt denied these allegations under oath. However, such behavior, while clearly improper, was not unprecedented — the FBI had wiretapped the defense attorneys of the Chicago 7 and this was one reason the convictions in that trial were overturned on appeal.[40]

The Aftermath

In the 50 years that have passed since the Dow Chemical action, most of the D.C. 9 left their positions in the Catholic Church. Arthur Melville, Joseph O’Rourke, and Michael Dougherty have since passed away. Bernie Meyers left the priesthood and became a world reknowned Ghandi impersonator. (Really.) Bob Begin was temporarily disowned by his family because his father thought he “was being duped by the communists.”[41]

But perhaps Sister Joann Malone’s experience best illustrates the tensions that the D.C. 9’s actions caused with the Church. When she tried to return to her job as a teacher at a Catholic school in St. Louis, a quarter of the student body stayed home, and in the ensuing frenzy the school closed for a week. According to Malone, parents were angry “not about anything having to do with the war, but because I had broken a law. That seemed to be the source of the outrage — that a nun would break the law purposely, openly, publicly.”[42] Quite frankly, this sort of behavior wasn’t expected from a nun.

But, to a large extent, that’s exactly the point. As Begin put it, “I think the notoriety was due to the fact that professional people would jeopardize their future and their careers completely in order to make a statement about the war.”[43] In vandalizing Dow Chemical, the D.C. 9 made a statement that no one could ignore.

Footnotes

- ^ “9 Protestors Held in Dow Break In,” Washington Post, March 23, 1969.

- ^ Patrick McGrath, “Dow Office Attacked, Files Scattered,”National Catholic Reporter, April 2, 1969.

- ^ Mark S. Massa, The American Catholic Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 103-108.

- ^ Religion News Service, “Priests, Others Siezed After Damaging Dow,” Catholic Transcript (Hartford, Connecticut) March 28, 1969.

- ^ Michael Slaski, phone interview by author, November 14, 2019.

- ^ Joann Malone, interview by author, October 15, 2019.

- ^ Slaski, interview.

- ^ Bernie Meyers, phone interview by author, November 8, 2019

- ^ Malone, interview.

- ^ The D.C. 9, “An Open Letter to the Corporations of America,” March 22, 1969. Courtesy of Joann Malone.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Robert Begin, phone interview by author, October 8, 2019.

- ^ Malone, interview.

- ^ Begin, interview, October 8, 2019.

- ^ Malone, interview.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Robert Begin, phone interview by author, October 18, 2019.

- ^ Philip Hirschkop, interview by author, October 17, 2019.

- ^ Douglas O. Linder, “The Chicago Eight Conspiracy Trial: An Account,” Famous Trials, https://famous-trials.com/chicago8/1366-home.

- ^ Hirschkop, interview.

- ^ United States v. Dougherty, 473 f2d 1113 (DC Cir. June 30, 1972).

- ^ Malone, interview.

- ^ Hirschkop, interview.

- ^ Hirschkop, interview

- ^ Thomas Lippman ,“Judge Spars With D.C. Nine as Trial Opens,” Washington Post, February 4, 1970.

- ^ “D.C. Nine Trial Begins; Dow Chemical Sued,” National Catholic News Service, February 6, 1970.

- ^ Thomas Lippman, “Court Fray halts ‘D.C. 9’ Trial,” Washington Post, February 7, 1970.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Hirschkop, interview.

- ^ Thomas Lippman, “Washington Dow Raiders Find Court Unsympathetic,” National Catholic Reporter, February 18, 1970.

- ^ Peter Osnos, “7 of ‘D.C. 9’ Found Guilty of Illegal Entry in Dow Case,” Washington Post, February 11, 1970.

- ^ Peter Osnos, “’D.C. 9’ Lawyer Gets 30 -Day Jail Term” Washington Post, February 12, 1970.

- ^ Osnos, “7 of ‘D.C. 9’ Found Guilty of Illegal Entry in Dow Case.”

- ^ Malone, interview.

- ^ Peter Osnos, “’D.C. 9’ Get Jail Terms For Raiding Dow Office” Washington Post, May 7, 1970.

- ^ United States v. Dougherty, 473 f2d 1113 (DC Cir. June 30, 1972).

- ^ Hirschkop, interview.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Background: Chicago 7 Trial,” Chicago Tribune, October 24, 2016.

- ^ Begin, interview.

- ^ Malone, interview.

- ^ Begin, interview.

![Hundreds of draft protestors stand outside the courthouse where the trial of the Catonsville Nine takes place, peace signs up in support of the Nine. (Source: William Morgenstern, [War and draft protest], 1968. Gelatin silver print. University Archives, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, UARC Photos-09-01-0025.)](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/street-rally-s_0.jpg?itok=E3FhlO92)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)