The C&O Canal Owes a Lot to Black Workers of the CCC

“After overcoming the obstacles that have confronted us in life, I look into full consideration the opportunities that [have] been at our door in the Civilian Conservation Corps. Assuring myself that every one of you have taken full advantage of these, I believe that you are well equipped to fight life’s battle.”[1]

These words were written by a man named Carl Palmer for a publication called the Tow-Path Journal. While this man’s name is not written in history books, and the Tow-Path Journal has been long forgotten, he is exemplary of hundreds of men who shaped local history in the forests of Maryland from 1938-1942. Palmer was a newspaper editor, a baseball player, a teacher of current events, and most notably, a member of an all-Black Civilian Conservation Corps company that worked to restore the decaying Chesapeake & Ohio Canal. These men laid the groundwork for the C&O Canal to become the National Historical Park that is enjoyed today.

Interestingly enough, the idea for a canal to extend the Potomac River was initially conceived by George Washington, when he was visiting the area in 1784.[2] The task ended up being more arduous, time-consuming and expensive than Washington anticipated, taking 11 million dollars and over 60 years to complete, and never achieving its namesake of connecting the Chesapeake Bay to the Ohio River.[3]

In other bad luck, the canal was always in competition with a younger and hotter method of transportation: railroads. In fact, the first railway in the United States—the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad—broke ground the same day as the C&O Canal. The two fought a bitter battle to connect the Eastern seaboard with the Midwest, and inarguably the B&O Railroad won: it was completed earlier, extended farther and transported goods faster than boats on the canal.[4] With two expensive floods causing major damages in 1889 and 1924, the C&O Canal became defunct.[5]

But, the story did not end there. Ironically enough, the C&O Canal’s future as a natural and historic destination was a glowing success compared to its relative failure as a functional method of transportation.

The Civilian Conservation Corps was a New Deal program launched by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1933 to put men to work on projects geared toward environmental conservation.[6] The CCC had a massive impact on the natural landscape of the country, ultimately planting 2.5 billion trees, constructing more than 800 parks and implementing measures to prevent soil erosion.[7] The efforts of this program greatly influenced the experience and perspective of the country’s natural beauties: as the twentieth century trudged forward, more and more Americans took their tourism to the great outdoors.[8]

The primary goal of New Deal programs was to provide economic recovery in a time of dire need. When the Great Depression was at its worst, unemployment in the country was over 20%, and Black Americans suffered disproportionate rates of joblessness at 2-3 times higher than Whites.[9] Because the CCC had a stipulation in its constitution that “no discrimination shall be made on account of race, color, creed or criminal records,” over 200,000 African American men were able to enroll, receiving the same wage as White enrollees.[10][11]

Unfortunately, racist practices were still a reality for African American corpsmen. In accordance with Jim Crow, all companies were segregated by race, yet all-Black companies fell to White leadership.[12] Further, there is evidence that African Americans were often given menial, administrative work, rather than the more skilled labor appointed to White enrollees.[13] Finally, the Director of the CCC placed a quota on Black recruits, ensuring that no more than 10% of enrollees were Black and that they could only be recruited in their home state. These policies were unfair on two levels: first, they didn’t account for higher rates of unemployment, and second they placed a limit that was smaller than the actual population of African Americans in a quarter of the states (and the District of Columbia.)[14]

In the D.C. area, there were 324 Civilian Conservation Corps companies. Yet, only three consisted of Black workers. This sheds light on the reality that New Deal programs prioritized the wellbeing and economic recovery of White men, over all others.

Nonetheless, the opportunity to work and receive a decent wage was meaningful to many Black corpsmen who were struggling during the Great Depression. As an orderly and assistant pay clerk from North Carolina said in a 1989 interview: “There were no jobs of a regular nature. Also it was a chance to send my mother $25 each month.” Another CCC enrollee, who worked in the kitchen for a company in New Bern recalls: “Times were very tough. My father was not making enough money to make ends meet so I joined the three C’s to help the family.”[15]

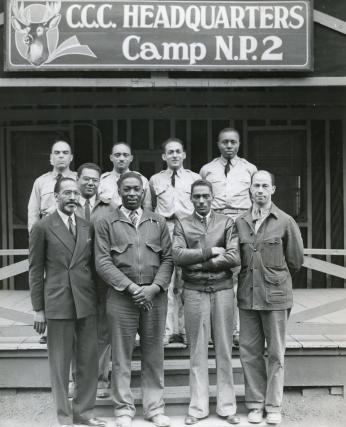

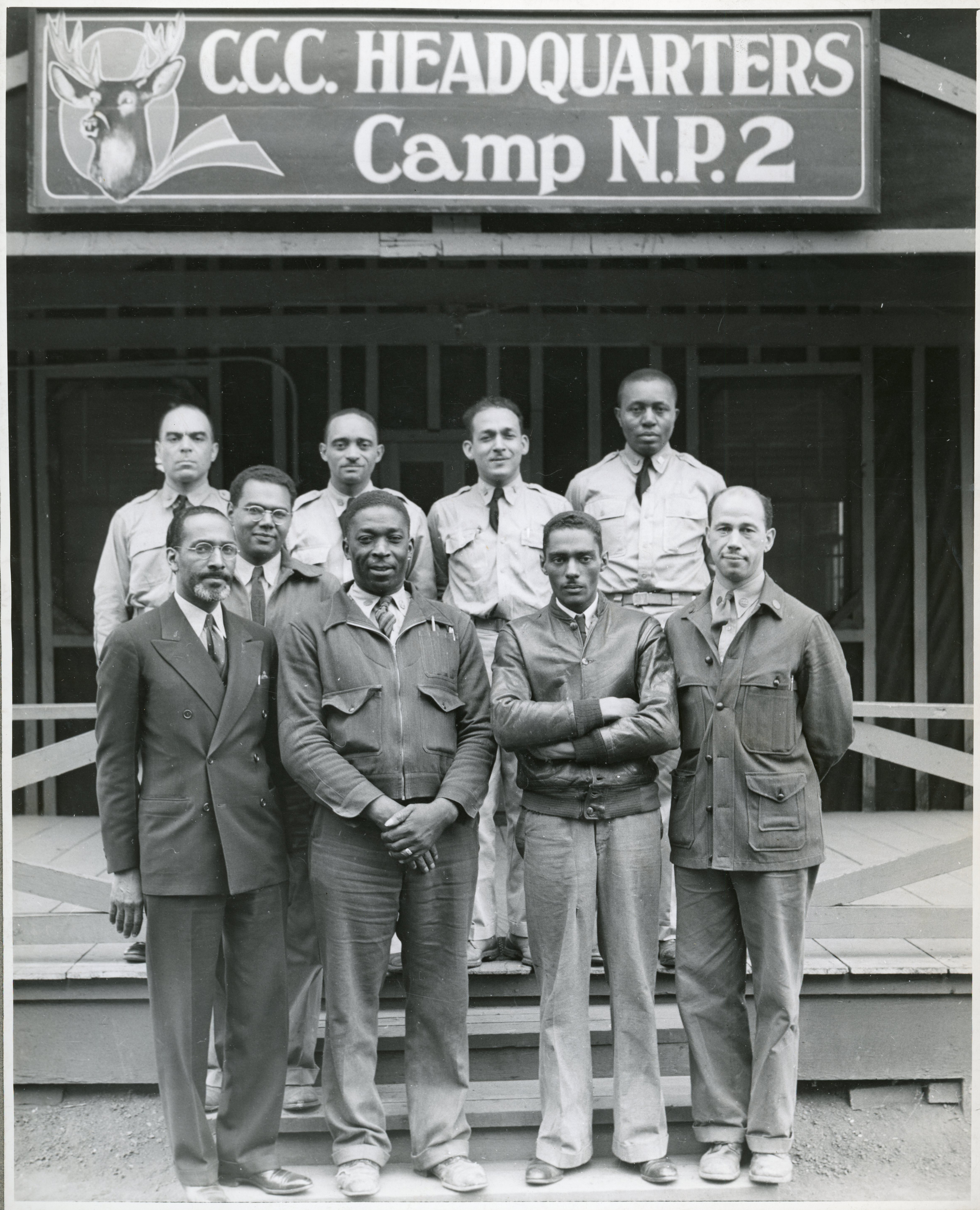

In 1938, two camps—known as NP-1-MD and NP-2-MD—were established in Cabin John, Maryland to restore the flood-damaged Chesapeake & Ohio Canal. These camps would house Companies 325 and 333, which were comprised of African American men from the greater D.C. area.[16] Over the next five years, these corpsmen cleared debris, repaired the towpath, removed vegetation, and installed facilities that would develop the canal into a recreational site, such as parking lots and latrines.[17] By the end of their tenure, these two companies excavated 22 miles of the canal by hand, from the length of Washington, D.C. to Seneca, Maryland. Beyond manual labor, these enrollees were also early actors in living history programs for visitors, leading horses that pulled boats, manning the bow and operating locks.[18]

Life at these camps was labor-intensive, regimented and reminiscent of life in the military. The bugles sounded a wake-up call each morning at 6:00 AM, and breakfast took place an hour later.[19] Meals were meant to be nutritious and well-balanced, and weight gain among workers was seen as evidence of improving health.[20]

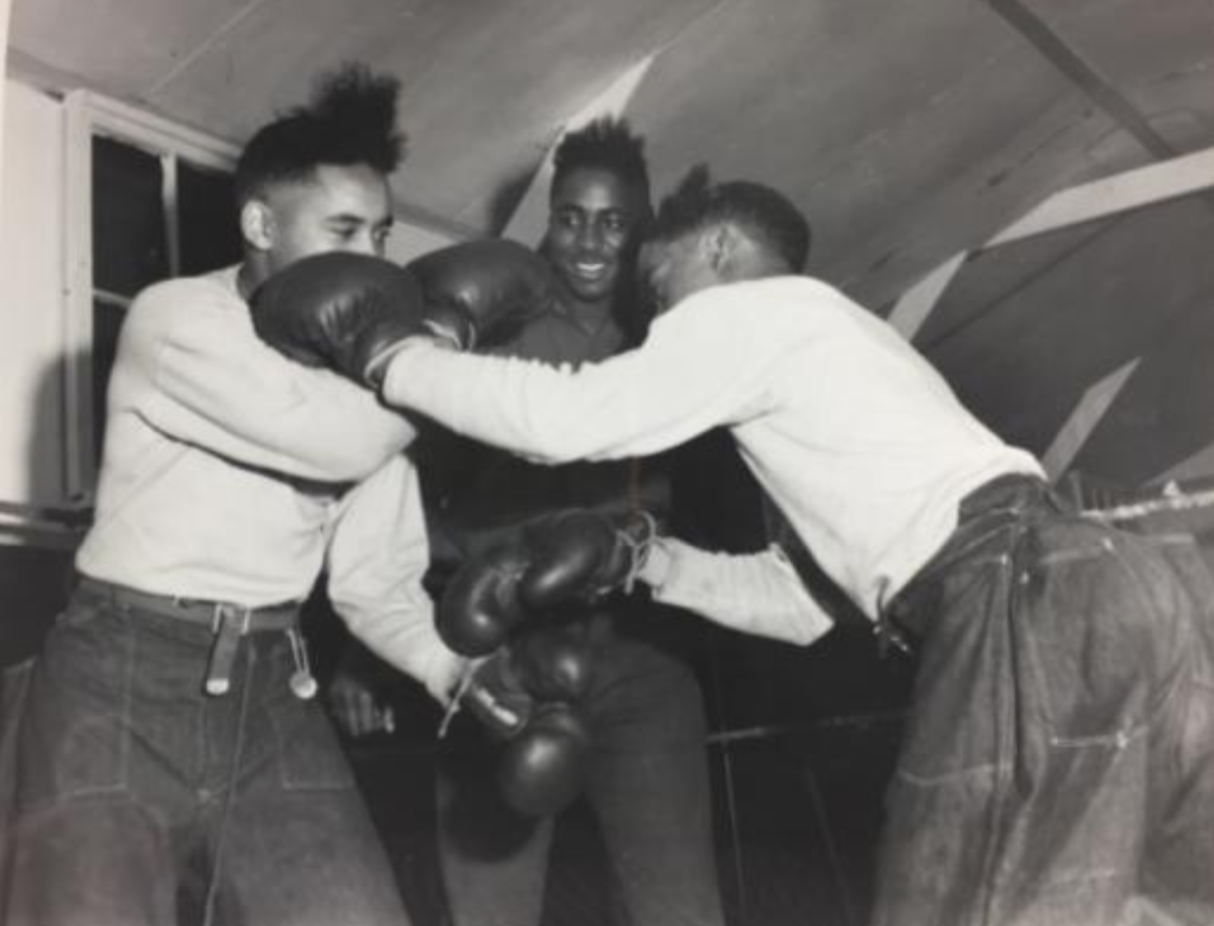

Fortunately, amidst laborious days and nutritious meals, there was room for a little fun. Co. 333 and 325 had access to a number of recreational activities including, ping pong, basketball, baseball and weekly movies. Enrollees could also volunteer at the company newspaper (the aforementioned Tow-Path Journal), give musical performances, attend Christian religious services and take trips to the capital.[21]

In one edition of the newspaper, an enrollee named James Carey takes pride in how workers beautified camps NP-1 and NP-2. He wrote:

“In comparison with the growth of a child so has the beauty of the camp grown. Where we once had bare patches of clay we now have grassy lawns. The barracks once rough and unfinished now are painted with attractive colors. The roads around camp were overcrowded with tall grass and baby trees, but now there is no more wilderness around the camp roads. The roads have been leveled and gravel has been spread in the place of the weeds that once grew there.”[22]

Arguably, education was the most important takeaway for CCC enrollees: academic and vocational skills attained at the Corps greatly improved candidacy for future employment, which was especially impactful for the many Black enrollees who came from underserved communities.[23] An Educational Report from Camp NP-2-MD cited the successes of the Educational and Training Program, with many examples of “conquered illiteracy,” new “vocational skills,” “secured jobs” and success in “college and trade schools.”[24]

Company 333 was lucky to be under the leadership of an Educational Advisor who went above and beyond the call of his post. C. Rushton Long had a rare leadership role as an African American college graduate in the CCC. By all accounts, Long was not just an educator, but also a coach, leader, and advocate for Black enrollees to be empowered during and after their tenure at the three C's. Of Long, historian Josh Howard writes: “His level of power, authority, and leadership was exemplary across the CCC. In studying dozens of other camps, no other educational advisor has displayed as much care or power as Long.”[25]

C. Rushton Long’s own words exuded with optimism:

“A great number of enrollees have entered camp with no objective in life and with a spirit of defeatism, but after being exposed to the camp’s general training opportunities for a period of time those same men have not only developed their educational, vocational and occupational skills but they have developed a wholesome perspective and attitude on life.”[26]

Work on the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal declined as the Second World War approached. Both camps closed in the early 1940s, and never reopened because the Civilian Conservation Corps ceased operations in 1942. President Eisenhower declared the C&O Canal a National Monument in 1961, and it officially became a National Historical Park in 1971.[27] While there are many groups and individuals to thank for making this landmark what it is today, a large debt of gratitude is due to the Black CCC men of Co. 325 and 333 who shaped the canal’s history with their hands.

Footnotes

- ^ Carl Palmer, “Farewell Address.” Tow-Path Journal, March 31, 1939.

- ^ Jacob Fenston, “You Can Sleep Inside A Centuries-Old C&O Canal Lockhouse, If That’s Something You’re Into.” DCist, Jun 28, 2019, https://dcist.com/story/19/06/28/you-can-sleep-inside-a-centuries-old-co-canal-lockhouse-if-thats-something-youre-into/.

- ^ Josh Howard, “‘Our Only Alma Mater:’ The Civilian Conservation Corps and the C&O Canal,” Special History Study, Dec 16, 2017, p 47, http://jhowardhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Howard-Josh-CCC-Canal-Final-photos-inline.pdf.

- ^ “Battle Between the C&O Canal and the B&O Railroad,” C&O Canal Trust. https://www.canaltrust.org/pyvactivities/railroad/.

- ^ "LOSSES BY FLOOD” The Washington Post (1877-1922), Jun 02, 1889. https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/docview/138323750?accountid=46320.

- ^ The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Civilian Conservation Corps.” Britannica: United States history, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Civilian-Conservation-Corps.

- ^ “Should Civilian Conservation Corps Camps Train for War?” The National WWII Museum New Orleans, Aug 6, 2018, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/should-civilian-conservation-corps-camps-train-war#:~:text=The%20Civilian%20Conservation%20Corps%20from,camps%20were%20in%20the%20west.

- ^ See yearly visitor statistics for Yellowstone National Park here: https://www.yellowstone.co/stats.htm.

- ^ Hannah Traverse, “Moving Forward Initiative: The African American Experience in the Civilian Conservation Corps.” Americorps, The Corps Network, Aug 17, 2017, https://corpsnetwork.org/blogs/moving-forward-initiative-the-african-american-experience-in-the-civilian-conservation-corps/.

- ^ Angela Sirna, “From Canal Boats to Canoes: The Transformation of the C&O Canal, 1938-1942,” West Virginia University, 2001, p 64, https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1811&context=etd.

- ^ Hannah Traverse, “Moving Forward Initiative.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Angela Sirna, "From Canal Boats to Canoes," p 67.

- ^ Josh Howard, “Our Only Alma Mater,” p 19.

- ^ Dr. Olen Cole Jr., “Work and Opportunity: African Americans in the CCC.” NCpedia; Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Spring 2010. Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History, https://www.ncpedia.org/history/20th-Century/ccc.

- ^ "State-By-State: Maryland.” Civilian Conservation Corps Resource Page, May 8, 2014, http://cccresources.blogspot.com/2014/05/state-by-state-maryland.html.

- ^ Lisa Pfueller Davidson and James A. Jacobs, “Civilian Conservation Corps Activities in the National Capital Region of the National Park Service HABS No. DC-858,”Historic American Buildings Survey, p 66-68, http://www.npshistory.com/publications/ccc/ccc-ncr.pdf.

- ^ Angela Sirna, “From Canal Boats to Canoes,” p 62.

- ^ Josh Howard, “Our Only Alma Mater,” p 85.

- ^ Ibid, p 71.

- ^ Ibid, p 65.

- ^ James Carey, “Camp Improvement,” Tow-Path Journal, June 30, 1939. From Angela Sirna, “From Canal Boats to Canoes,” p 70.

- ^ Angela Sirna, “From Canal Boats to Canoes,” p 73.

- ^ From Pfeuller Davidson and Jacobs. “CCC Camp Educational Report – NP-2-MD,” Box 94, Entry 115, RG 35, Aug 25, 1939.

- ^ Josh Howard, “Building a Future: CCC Education Along the Canal.” C&O Canal Trust, Feb 2018, https://www.canaltrust.org/2018/02/building-a-future-ccc-education-along-the-canal/.

- ^ Angela Sirna, “From Canal Boats to Canoes,” p 76.

- ^ Ibid, p 2.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)