Thomas Jefferson's Missing Daughter

Over the course of the last few decades, the unequal relationship between Thomas Jefferson and his slave, Sally Hemings, has come to dominate discussions of Jefferson’s legacy as a politician and as a man. While the question of how to approach the man who wrote the Declaration of Independence and never freed the mother of his children is one that will undoubtedly continue to spark fierce debate for years to come, the Jefferson-centric narrative often neglects the unique experiences of those children. Harriet Hemings was the daughter of the most powerful man in the country and an enslaved woman thirty years his junior. She grew up in a world where she was both a Jefferson and a slave and lived as both a Black woman and a white woman over the course of her life.

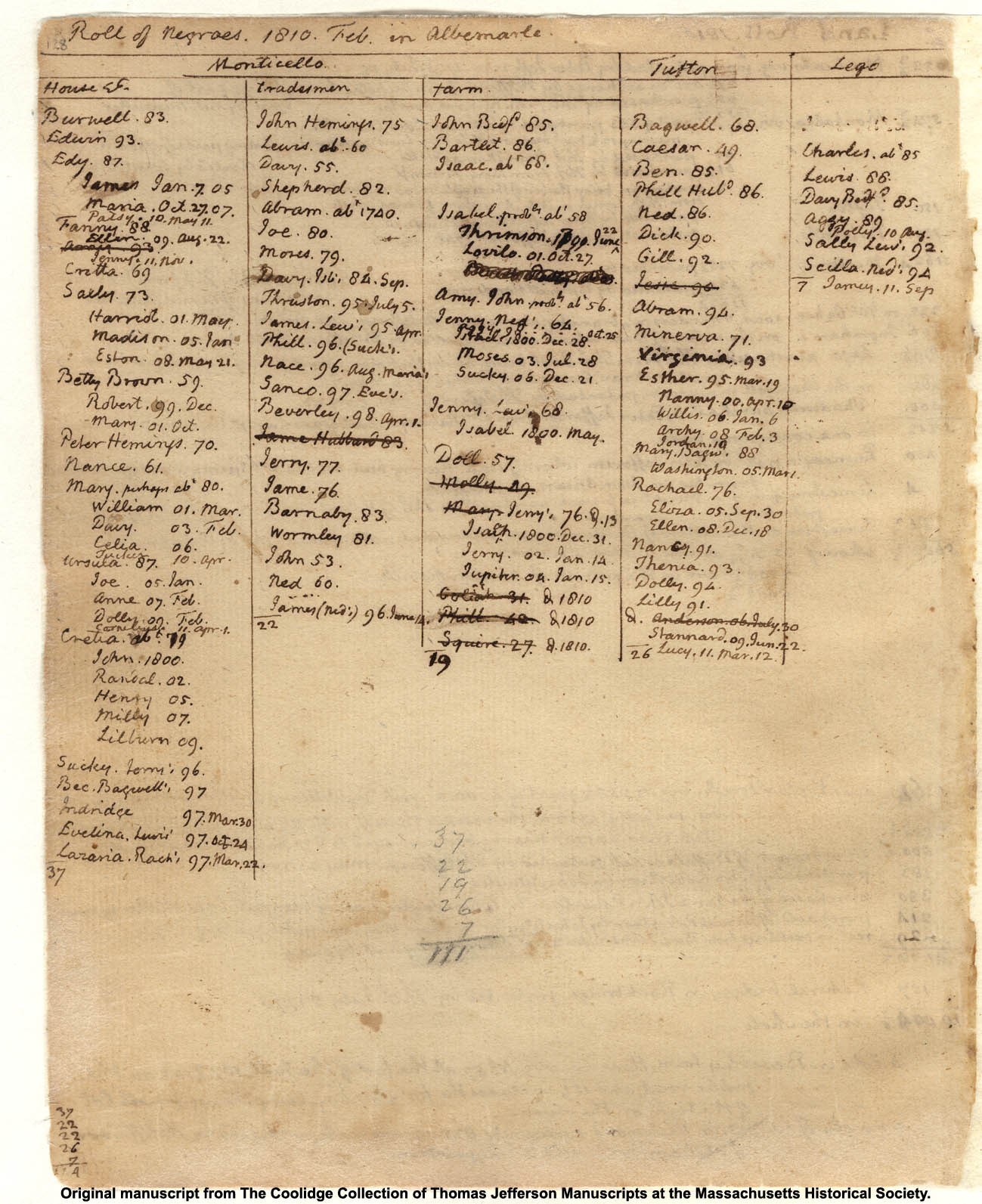

Harriet Hemings was born in May 1801 on Jefferson’s estate, the second daughter to bear the name after the death of her elder sister in 1797.[1] Although the exact circumstances of her early life have been lost to time, those details that are known suggest that Harriet experienced a childhood defined by contradictions. Harriet’s mother was herself the child of a mixed-race woman and a white master; as a result, Harriet and her brothers had a high enough percentage of European ancestry that they would have been considered white under Virginia law.[2] The children greatly resembled their father, to the extent that their parentage was an open secret among Jefferson’s neighbors.[3] They also experienced relatively privileged positions in the hierarchy of the plantation. According to Harriet’s younger brother Madison, Sally secured a promise from Jefferson that he would free their children when they turned twenty-one.[4] Until then, Harriet worked as spinner while her brothers apprenticed as carpenters, relatively desirable jobs compared to the hard agricultural labor demanded of most of the enslaved people on the plantation.[5]

Although the siblings had a unusually favored position relative to the other enslaved people at Monticello, Harriet and her brothers would likely have been regularly confronted by the unfair circumstances of their birth. Madison’s account of their childhood notes that while Jefferson doted on his acknowledged grandchildren, “he was not in the habit of showing partiality or fatherly affection to us children."[6] The historian Catherine Kerrison also notes that although the members of the Hemings family were specifically exempted from the terror of the overseers, they nonetheless would not have been able to avoid seeing the whippings and other terrors inflicted upon the other slaves on the plantation.[7] When Harriet was eleven, the entire enslaved population of Monticello was forced to watch the public whipping of a man accused of theft.[8] Harriet and her brothers may have been the master’s children but they were not free from the system he maintained.

Jefferson ultimately fulfilled his promise to Sally to free their children. Around 1821, Harriet and her older brother Beverley were tacitly allowed to escape the plantation.[9] Beverley left first. Edmund Bacon, one of the head overseers on the estate, claimed that he assisted Harriet in leaving the estate “by Mr. Jefferson’s direction I paid her stage fare to Philadelphia and gave her fifty dollars.”[10] Her two younger brothers, Madison and Eston, were eventually freed in Jefferson’s will.[11] Sally Hemings never received her freedom from the father of her children.[12]

Although Harriet now had the freedom to move as she pleased, she was not free of the cruel influence of slavery. Thomas Jefferson never officially freed Harriet or Beverley; he recorded them as having “run” in 1822.[13] Had she chosen to live openly as herself, she may have been hunted down by slave catchers and dragged back to her father’s estate in chains. In order to secure herself, Harriet chose to conceal her identity and use the fact that she could pass as white to move to Washington and marry into white society. In 1873, Madison wrote that he believed she was successful in hiding her true identity.

Harriet married a white man in good standing in Washington City, whose name I could give, but will not, for prudential reasons. She raised a family of children, and so far as I know they were never suspected of being tainted with African blood in the community where she lived or lives. I have not heard from her for ten years, and do not know whether she is dead or alive. She thought it to her interest, on going to Washington, to assume the role of a white woman, and by her dress and conduct as such I am not aware that her identity as Harriet Hemings of Monticello has ever been discovered.[14]

After this statement, the name “Harriet Hemings” disappears from known history.

The mystery surrounding the ultimate fate of Harriet Hemings draws instinctive curiosity. Both the historians Pearl M. Graham and Catherine Kerrison devote a portion of their published writings to try and identify women who may have been Harriet after her concealment.[15] However, it very possible that Harriet Hemings will never be found. If she achieved her goal and fully disappeared into Washington’s white society, there may be no records of her to find.

Footnotes

- ^ Pearl M. Graham, “Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings,” The Journal of Negro History 46, no. 2 (Apr. 1961): 95.

- ^ Catherine Kerrison, Jefferson’s Daughters: Three Sisters, White and Black, in a Young America (New York: Ballantine Books, 2018), 22; Ibid., 196.

- ^ Kerrison, Jefferson’s Daughters, 252.

- ^ Madison Hemings, “Life Among the Lowly,” Pike County Republican (Waverly, Ohio), March 13, 1873.

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed, The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008), 797-798.

- ^ Hemings, “Life.”

- ^ Kerrison, 209; Ibid., 254-255.

- ^ Ibid., 255.

- ^ Gordon-Reed, Hemingses, 652.

- ^ Kerrison, 268.

- ^ Hemings.

- ^ Graham, 98.

- ^ Kerrison, 266.

- ^ Madison.

- ^ Graham, 98-99.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)