The "Capitalsaurus": How a Dinosaur That Never Existed Became an Official Mascot of D.C.

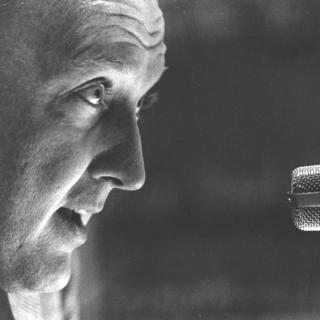

(Source: Matthew Carrano, Smithsonian)

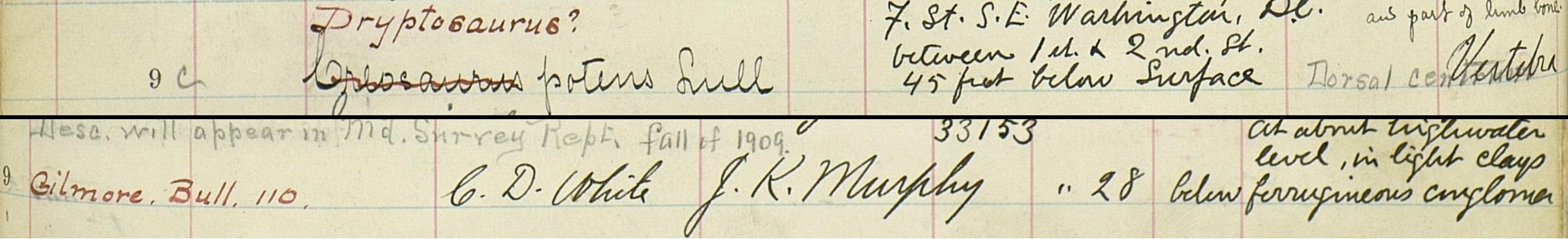

In January of 1898, contractor James K. Murphy's crew was hard at work digging along F St. between First and 2nd St. SE, just south of the U.S. Capitol. The project was part of the district's lengthy effort to upgrade its sewer system, which dated to 1810 and was among the oldest in the United States,1 though something much older was about to stop the crew in its tracks – at least temporarily.

As their shovels sifted through the light clay soil, the workers uncovered a rather unusual looking rock. Not quite sure what it was – or what should be done with it – Murphy turned it over to Smithsonian geologist C. David White for inspection. To White's trained eye, this was no ordinary rock. It was a fossil – specifically, a vertebra from some sort of creature who had met its demise millions of years before Washington, D.C. was a dot on a map.

and the star of this story. (Source: Smithsonian)

What sort of creature exactly, White couldn't say for certain. (As a paleobotanist, he had always been more of a flora fellow than a fan of fauna.) White dutifully entered the specimen into the Smithsonian's catalog, giving it the identifier USNM 3049, and tucked it safely into a box where it would sit for the next decade.2

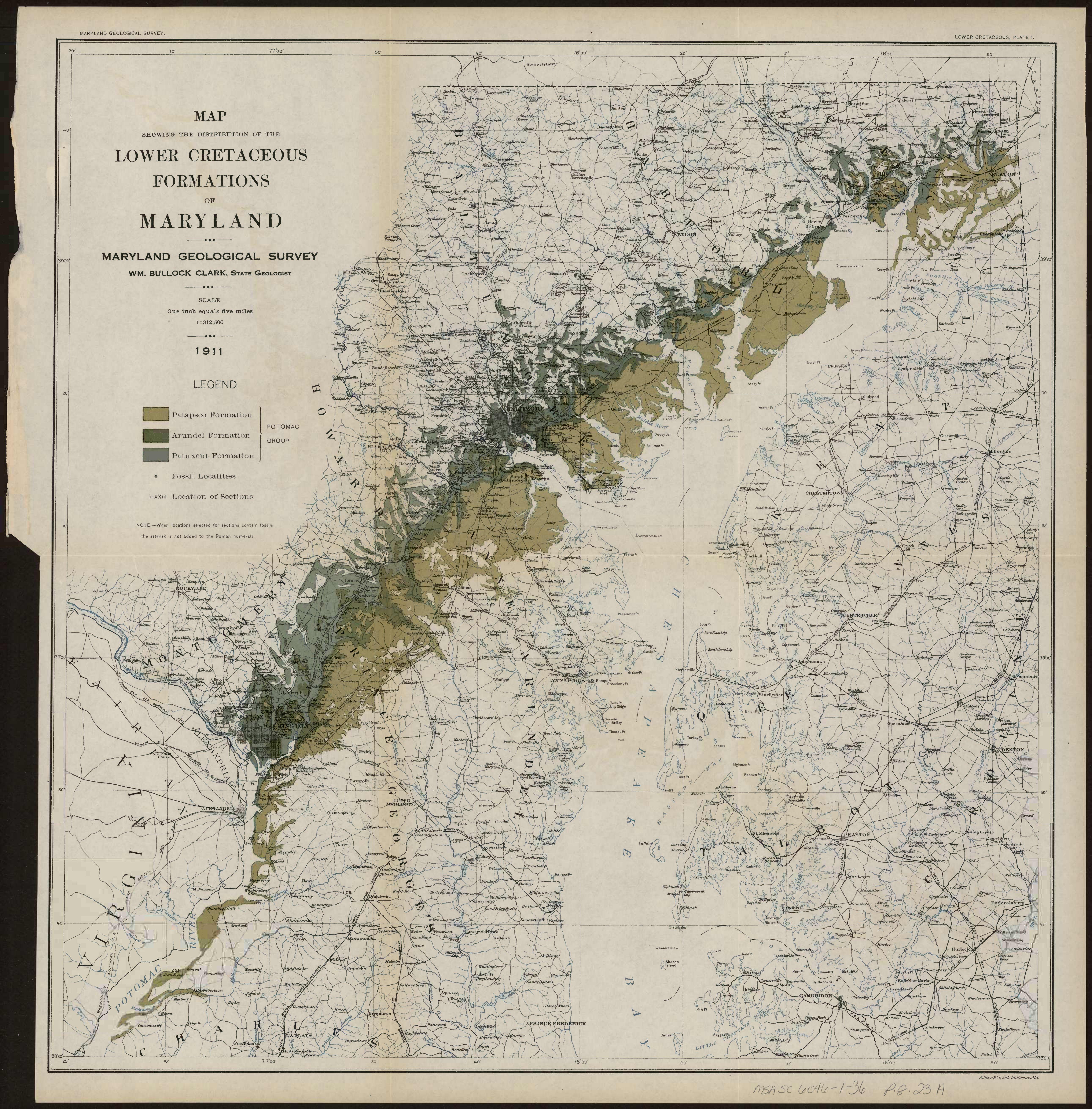

It likely would have stayed in that box, unknown and unnamed, for much longer had the governor of Maryland not commissioned a series of systematic reports for the Maryland Geological Survey. The survey tapped Dr. Richard Swann Lull, associate professor of vertebrate paleontology at Yale University and an associate curator at the school’s Peabody Museum. While pouring through the Smithsonian’s horde of local specimens, he found the box containing USNM 3049, still waiting patiently for classification.

Lull identified the specimen as a caudal vertebra from the tail area of a carnivorous, bipedal dinosaur otherwise unknown to the local region.2 Though unknown, he noted that the fossil was most similar to a vertebra of one of Yale’s own prehistoric specimens, the Creosaurus atrox (“terrible flesh lizard”). But, the match wasn’t quite close enough for Lull to be confident, so he designated the D.C. specimen as a brand new subspecies, Creosaurus potens (“powerful flesh lizard”). He concluded his report by observing that:

“This vertebra represents by far the largest carnivore known from [Maryland’s] Arundel formation.”3

After years shelved in a dusty box with only a catalogue number, the sewer bone finally had a classification. It belonged to the Creosaurus family, large meat eaters who were close relatives of the Allosaurus (“strange lizard”)… That is until a second paleontologist got his hands on the fossil. This is where things get a bit... taxonomy heavy, so hang on tight!

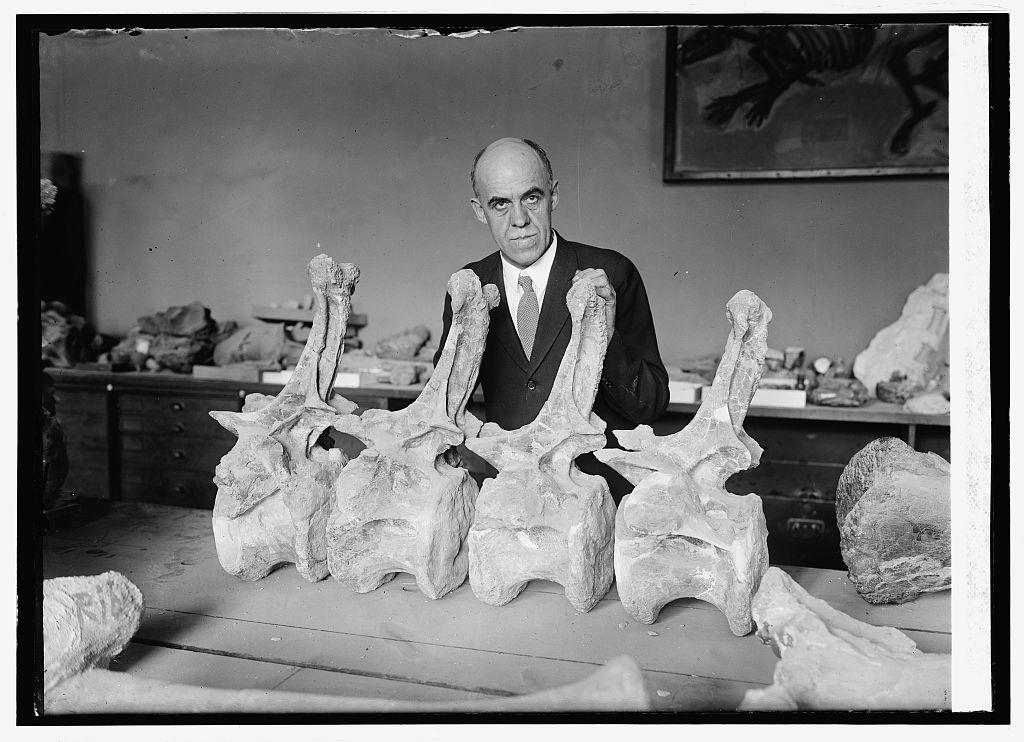

Only a few years out of the University of Wyoming, Charles Whitney Gilmore was brought onto the Smithsonian team. Young and full of energy, he became a paleontological printing press, publishing some 170 scientific papers over the course of his career.4 One of his many articles, a Smithsonian bulletin published in 1920, took aim at the genus of Creosaurus altogether.5 With the insight offered by recent discoveries, Gilmore observed that Creosaurus and Allosaurus were a bit too closely related, in fact he claimed there were no distinct characteristics separating the two at all! Therefore the two were synonymous, and all Creosaurus specimens should be reclassified as Allosauruses, since the latter was the older classification.6

That would make the mysterious Capitol Hill dino an Allosaurus then, right? Well, not quite… because if there was one thing that Gilmore and Lull both agreed on, it was that whatever creature this fossil belonged to, it was not an Allosaurus.7, 8

Having spent much of his curatorial career trying to reconcile the vast number of dinosaurs given various names by various paleontologists throughout the early, messier days of the discipline,9 Gilmore cautiously reclassified the fossil known as USNM 3049 as belonging to Dryptosaurus ? potens (“powerful tearing lizard”). His inclusion of a question mark signified that, even though he was confident that the vertebra didn’t actually belong to the Dryptosaurus family, he felt the fossil matched specimens of that species recently discovered in New Jersey more closely than anything else. It was a placeholder label of sorts, and Gilmore was counting on an inevitable overturning of his classification:

This species becomes Dryptosaurus ? potens (Lull) until such time as the discovery of adequate materials will permit the determination of its true affinities.10

As time went on and paleontology matured as a science, the bones discovered and classified by the likes of Lull, Gilmore, and their contemporaries were assembled and erected in grand museums like the American Museum of Natural History, allowing the public to gaze upon these boney behemoths in their full glory. These exhibits did more than just inform, they inspired the next generation of paleontologists – which is where our story gets really interesting.

Enter Dr. Peter Michael Kranz.

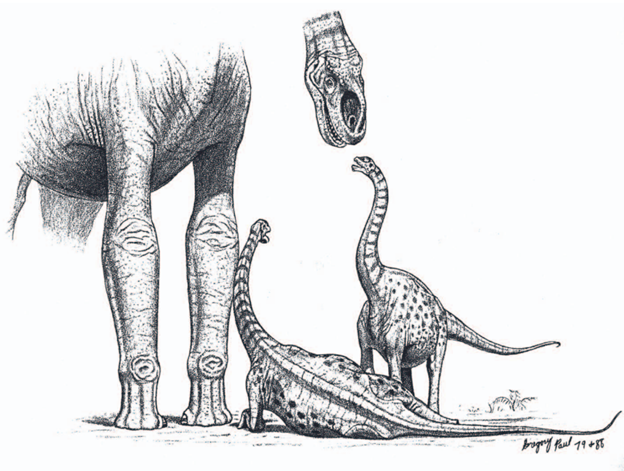

Elementary class about fossils. (Source: "I Can Find a Dinosaur Myself")

Growing up inspired by the works of his predecessors, Kranz cared about dinosaurs from the start. After moving to the D.C. area in the 1980s, Kranz did what any paleontologist in a new land would, and read everything available to catch himself up on the state of fossilized affairs in the region. During this research, he came across Lull’s initial classification, and later Gilmore’s reclassification, of the curious D.C.-based dinosaur. By this time, the fossil had been considered a Dryptosaurus longer than Kranz had even been alive, but Dr. Kranz was born to dig up old bones, both literally and figuratively. Taking Gilmore’s question-punctuated-classification as an invitation to reexamine the species, Kranz got to work. As Gilmore predicted, in the years since he wrote that the bone was closest to a Dryptosaurus, many more discoveries about that species had been made, so when Kranz compared the mysterious USNM 3049 bone against the newer Dryptosaurus discoveries, he proclaimed that that classification was no longer an adequate fit.11

Since this vertebra apparently didn’t belong to any dinosaur known in the fossil record anywhere else in the world, Kranz figured it deserved an identity as unique as it was. Highlighting the fact that it had been found within the small reach of the nation’s capital, he christened it the "Capitalsaurus" in a 1990 issue of Washingtonian magazine.12

For the moment the beast is labeled a "dryptosaurus," but... local paleontologist Peter Kranz would like it to be known as "capitalsaurus," Washington's very own giant reptile.13

The playful moniker was a great fit for some of Kranz’s other projects. When he wasn’t sifting through fossils, he taught science to everyone from preschoolers to graduate students.14 Over the years, he would lead dino excavations for summer camps15 and managed the Dinosaur Fund to further local research.16 (Oh, and he did birthday parties, Pith helmet and all.)17 It was this love of paleontology mixed with a belief that the prehistoric past should be more accessible to the public that would eventually bring him before the D.C. City Council to lobby on behalf of the “Capitalsaurus”. But first, he had a date in Annapolis for a similar project.

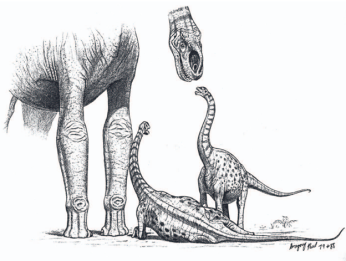

perhaps one of the first dinosaurs discovered in

the United States, was some 60 feet long and 30

feet tall! (Source: Dinosaurs of D.C.)

In 1992, Kranz led an effort to get the Maryland general assembly to take up the Astrodon johnstoni (“star tooth”), a long-necked herbivore and the first dinosaur discovered in the Free State, as the state’s official dinosaur.18 However, the state legislature was facing a budgetary crisis at the time and some members like Senator John A. Cade thought it was foolish to pass symbolic legislation with a potential crisis looming. “I just wonder what the taxpayers will think,” the senator told a Washington Post reporter, “it’s Nero fiddling while Rome burns.”19 The motion failed in the house by two votes.20

Not to be discouraged by cynical lawmakers, Kranz returned in 1998, armed with a new plan and a convoy of school kids from, appropriately, Flintstone Elementary. The child lobbyists went around and, in one of the cutest examples of quid pro quo ever, gave a plastic toy of a long-necked dino to lawmakers who agreed to vote for the bill.21 “We realized that kids were effective lobbyists for state dinosaur bills,” Kranz reflected, “the whole point of state dinosaurs… is to give a simple thing for people to focus on that promotes the state… promotes education, promotes learning… and then of course the legislatures like the fact that the kids were learning about the legislative process.”22 Thanks to the Flintstone kids, the Astrodon johnstoni joined Maryland’s roster of state symbols.23

prepare to lobby the D.C. Council on behalf of the

"Capitalsaurus", which adorns the wall behind them.

1998, (Source: The Washington Post)

Kranz had cracked the code — no politician, no matter how fossilized their hearts may be, could say no to school children. With one official dino title under his belt, Kranz turned his sights to D.C.’s city council, and he knew just the dinosaur for the job…

Kranz teamed up with staff members from two of the elementary schools where he taught science. Julia Hurdle-Jones brought fifth and sixth graders from Smothers Elementary, while Vice Principal Rosalie Huff lent support from River Terrace Elementary.24 On April 28, 1998, the cretaceous crusaders descended onto the city council chambers.25 Jones thought this was an excellent lesson in civics and community engagement for the kids, and she even wrote a song for them to chant as they went office hopping, serenading the council members at their desks.26

We lobbied throughout this building for two hours, going from office to office, singing our song.

-Ashley Coleman, 12.

It'll be a good learning experience of us to be here lobbying... I think the bill should be passed because we put a lot of work and effort into this assignment.

-Damien Raeford, 11.27

The junior lobbyists proved successful, as Council Chairwoman Linda W. Cropp brought the “Official Dinosaur Act of 1998” up for vote the very next week. With unanimous support from the council and the mayor, the “Capitalsaurus” became the official dinosaur of the District of Columbia on September 30, 1998, one hundred years after the initial discovery.28

First & F St. SE (Source: Hunter Spears)

Not everyone was fully on board, however. The Smithsonian Institution stressed that, despite the endearing lobbyists, there were no scientific publications which used the term “Capitalsaurus” to describe unique attributes of a species, thus the term had no scientific bearing. (This is why throughout this article you see “Capitalsaurus” in quotes while other dinos like Allosaurus are italicized.) The institution still holds that “the body of the bill muddled the science itself."29

In the end, the council decided that the Smithsonian’s concerns, while well founded, were not a solid enough reason to suspend their plans and even designated the discovery site at the 100 block of F St. SE as "Capitalsaurus Court."30 A few years later, Mayor Anthony Williams joined in recognized the discovery date as well.31

Now, therefore, I, the mayor of the District of Columbia, do hereby proclaim January 28, 2001, as "Capitalsaurus Day" in Washington, DC.32

Kranz says that the “Capitalsaurus”, like any symbol, can serve to unify a jurisdiction and lead to education in important local topics. It can also lead to, well, fun. Although the local government never took up the kids’ idea of minting commemorative “Capitalsaurus” license plates,33 other groups have seized on the region’s new (if you can call something 110 million years old new) mascot. For example, when the Capitol Hill Arts Workshop installed animal based art sculptures onto street signs as part of the Capitol Hill Alphabet Animal Art Project (a sheet metal dog on D St., for example) artist Charles Bergen got creative with his contribution.34 If you visit Capitalsaurus Ct. & F St. SE today, you will see Bergen’s depiction of a “Capitalsaurus” chasing a Falcarius (“sickle cutter”) through DC’s prehistoric savannahs.35 In another nod to the late local resident, Hellbender Brewing Company released a limited run “Capitalsaurus” wheat beer in 2019.36, 37

"Capitalsaurus" chasing a Falcarius. The sign is

part of the Capitol Hill Alphabet Animal Art Project.

(Source: Hunter Spears)

All that said, it bears repeating that the final word in science is typically based more on taxonomical descriptions of species and less on mayoral decrees and beer labels. So, if you visit the website for the Smithsonian’s archive you will see that the specimen still holds its very first moniker, Creosaurus potens Lull, 1911.38 Matthew Carrano, Curator of Dinosauria at the Smithsonian, says he believes it will likely remain without an official designation because identifying this fossil is a uniquely difficult job. “It is unfortunately not a very well-preserved vertebra, missing many parts that scientists like to see when trying to make such identifications,” he remarked over email. In fact, there is even some debate that D.C.'s sewer fossil belonged to a meat-eating dinosaur at all!39

What does all this mean for the “Capitalsaurus”? Well, the actual dinosaur who lived and died in Washington, B.C. may never be identified because the only clue it left behind just doesn’t give that much helpful information, and any other clues have been paved over and are unlikely to be unearthed anytime soon. So, we’ll just have to be content with our modern creation. You also aren’t likely to see the tailbone on display at the Smithsonian, as the institution is not in the habit of displaying specimens they themselves can’t identify. But while the “Capitalsaurus” may not have ever actually existed, it does have its own official day of recognition, which is more than most dinosaurs, real or otherwise, can say… or roar, rather.

Footnotes

- 1

“History - Sewerage System,” History - Sewerage System, DC Water, last modified 2017.

- 22 “Creosaurus potens Lull entry,” Department of Geology specimen intake ledger, initial entry 1898, provided to the author by Smithsonian Institution February 1, 2023.

- 3 The Arundel Formation is a local geological formation spanning throughout the Maryland region. Named for Anne Arundel county, the formation consists largely of clay, making it ideal for preserving fossils.

- 4

“Historical Profile: Charles W. Gilmore (1874-1945),” Park View, D.C., last modified September 22, 2010.

- 5

Charles W. Gilmore, “Osteology of the Carnivorous Dinosauria in the United States National Museum, with Special Reference to the Genera Antrodemus (Allosaurus) and Ceratosaurus,” United States National Museum, Bulletin 110, (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1920), 9, 10, 20, 30, 116-121.

- 6

For accuracy, it should be noted that when Gilmore collapsed multiple genera into one, the name he actually suggested to be used was Antrodemus (“chamber bodied”), as this name was older than Allosaurus so it should take priority. Paleontologists agreed, and for some fifty years dinosaurs previously known as Allosaurus, Creosaurus, and many others were considered Antrodemuses. This was the case until James H. Madsen Jr. argued in 1976 that the fossils from which the name Antrodemus originated from in 1870 (the type specimen) were not as reliable for basing an entire genus on as the Allosaurus type specimens were. Following Madsen’s article, all the creatures Gilmore condensed under the umbrella of Antrodemus henceforth belonged to the Allosaurus genus. James H. Madsen Jr. “Allosaurus fragilis: A Revised Osteology,” Utah Geological Survey Bulletin 109 (Salt Lake City: Utah Geological Survey), 11-12.

- 7 Lull, “Systematic Paleontology,” 186-187.

- 8 Gilmore, Bulletin 110, 117-118

- 9 The early days of paleontology were like the Wild West. Some paleontologists, namely rivals Othniel Marsh and Edward Cope, went to questionable lengths to win a race to discover more dinosaurs than their opponent. At best, this resulted in an over-classification of the same dinosaur species to inflate their numbers, and at worst ended with the scientists using dynamite on their own fossil pits at the end of a dig to prevent their rival from scavenging undiscovered bones. Consequently, much of Gilmore’s job was making sense of the excessive classifications in Marsh’s collections acquired by the Smithsonian. This extreme period is referred to as “The Bone Wars”, and the author recommends Michael Crichton’s Dragon Teeth for a historical fiction retelling of this legendary vendetta.

- 10 Gilmore, Bulletin 110, 119

- 11

Peter M. Kranz, Dinosaurs of the District of Columbia (Washington, D.C.), 14.

- 12 Howard Means, “The Great Outdoors,” Washingtonian, April, 1990, 125.

- 13 Howard Means, “The Great Outdoors,” Washingtonian, April, 1990, 125.

- 14

“Biography,” About, Dinosaur Fund, accessed January 25, 2023.

- 15

“Dinosaur Camp” Programs, Dinosaur Fund, accessed January 25, 2023.

- 16

“Dinosaur Funds Programs” Programs, Dinosaur Fund, accessed January 25, 2023.

- 17

Michael E. Rune, “Fossil Fueled”, The Washington Post, April 11, 2002.

- 18

While this story is about the “Capitalsaurus”, the Astrodon johnstoni has an interesting history as well. In 1858, Maryland dentist Christopher Johnston came into possession of two strange giant teeth. When he cut them in half he noticed a star like formation, and named the beast they belonged to Astrodon, meaning “star tooth”. Had he been a paleontologist and known that a specimen is only formally named if the unique qualities of the fossil are described, the Astrodon would have been the second dinosaur species identified in the United States. Alas, he was a dentist. Even if it wasn’t one of the first identified, that didn’t stop a local from writing a poem about it! Astrodon. Astrodon johnstoni, the Maryland State Dinosaur. The Story of the Astrodon.

- 19

Dan Beyers, “Turning From ‘Doomsday’ to Extinction,” The Washington Post, February 1, 1992.

- 20 Peter M. Kranz, telephone call with author, January 26, 2023.

- 21 Peter M. Kranz, telephone call with author, January 26, 2023.

- 22 Peter M. Kranz, telephone call with author, January 26, 2023.

- 23

“Maryland State Dinosaur,” Maryland at a Glance, Maryland State Archives, accessed January 27, 2023.

- 24 Peter M. Kranz, telephone call with author, January 26, 2023.

- 25

Vanessa Williams, “Making No Bones About Their Goal,” The Washington Post, April 29, 1998.

- 26

Vanessa Williams, “Making No Bones About Their Goal,” The Washington Post, April 29, 1998.

- 27

Vanessa Williams, “Making No Bones About Their Goal,” The Washington Post, April 29, 1998.

- 28

Official Dinosaur Act of 1998, D.C. Code § 1-161, (September 30, 1998).

- 29

Riley Black, “’Capitalsaurus,’ A D.C. Dinosaur,” Smithsonian Magazine, December 28, 2010. The Smithsonian’s critique that the bill muddies the science is not unfounded, as the bill remarks that the “Capitalsaurus” may have been an ancestor of the Tyrannosaurus Rex. While not necessarily incorrect, is likely included more due to the fame of the latter dino, rather than because of any close genealogical connection the two may have shared.

- 30

Designation of Capitalsaurus Court Act of 1999, D.C. Law L13-041, (October 20, 1999).

- 31

“Capitalsaurus Day,” Resources, Dinosaur Fund, accessed January 20, 2023. The author was not able to obtain any evidence of a mayoral proclamation outside of the Dinosaur Funds’ website, however the Council of the District of Columbia did pass a ceremonial resolution acknowledging the day. The only problem being that they passed it a week late! A Ceremonial Resolution in the Council of the District of Columbia. Capitalsaurus Day Resolution of 2001.

- 32

“Capitalsaurus Day,” Resources, Dinosaur Fund, accessed January 20, 2023. The author was not able to obtain any evidence of a mayoral proclamation outside of the Dinosaur Funds’ website, however the Council of the District of Columbia did pass a ceremonial resolution acknowledging the day. The only problem being that they passed it a week late! A Ceremonial Resolution in the Council of the District of Columbia. Capitalsaurus Day Resolution of 2001.

- 33

Unknown author, “’Them Dino Bones’,” The Washington Post, April 16, 1998.

- 34

Fritz Hahn, “Finding these artful animals around Capitol Hill is as easy as ABC,” The Washington Post, July 22, 2021.

- 35

“Capitolsaurus Chasing a Falcarius,” Charles Bergen Studios, accessed January 26, 2023.

- 36

“Capitalsaurus,” Hellbender Brewing Company, Untappd, accessed February 1, 2023.

- 37

“Hellbender ‘Capitalsaurus’ Beer Release Party and Print Fest,” Capitol Riverfront, accessed February 1, 2023.

- 38

“Creosaurus potens Lull, 1911” Specimen USNM V 3049, Department of Paleobiology Collections, Smithsonian, accessed January 20, 2023. When one of the three small images of the fossil are enlarged, the description reads “Description: Creosaurus potens Type. Incorrectly named ‘Capitalsaurus’.”

- 39 Matthew Carrano, email message to author, January 31, 2023.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)