The Federal Government's $15 Million Cat

Being a spy is stressful. It’s hardly as glamorous as James Bond would have you believe. Much of your work is mundane data-sifting, and when it’s not, you trade in priceless things: state secrets, human lives, and very expensive gadgets. The stakes are sky-high. It’s not a job most people would want.

You certainly wouldn’t want to be the spies parked outside the Soviet embassy in 1967, in their van full of switches and equipment. You wouldn’t want to be the spy who has to tell your supervisor that you could only watch helplessly as five years of research and fifteen million dollars vanished in one screech of tires.

Welcome to Operation Acoustic Kitty.

In the 1960s, the CIA had a problem. Bugs—hidden microphones placed on people or their surroundings—were a crucial piece of spyware, but their receivers weren’t very good. They couldn’t filter out irrelevant noise, so targets’ conversations were often lost amid silverware clinking, furniture squeaking, or music playing.1 The CIA needed some kind of filter that would dampen irrelevant noise, like the cochlea of a human ear. Or an animal’s.

Around the same time, the CIA was monitoring a target in Asia. They noticed that stray cats would wander unimpeded into high-security areas and even top-secret meetings. No one paid them any mind. According to Bob Bailey, who had previously trained dolphins for the Navy, this gave the CIA an idea: put a microphone into something as innocuous as a cat, use its cochlea as a natural noise filter, and you’ve made the perfect mobile bugs.2

The problem? No one had ever even attempted anything like it.

It’s no secret that the CIA has tried some bizarre experiments in its time. From attempting to harness human psychic powers to increasingly outlandish plans to assassinate Fidel Castro, sometimes the Agency seemed to think more about whether it could than whether or not it should. But with Cold War paranoia and nuclear fears running high, the CIA was very interested in anything that could give them a chance to peek behind the Iron Curtain.

And, well, Project Acoustic Kitty was so outlandish no one would ever see it coming. In 1962, the techs and case officers at the Office of Technological Service came up with a plan: they would implant a microphone and a tiny transmitter into a cat’s ear canal and train it to follow audio cues towards a target. Then it would lounge about, listening to sensitive conversations before wandering back out to its handlers, loaded with secrets.

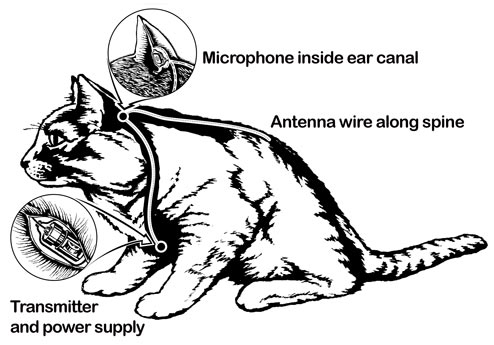

Together, the Office of Technological Service and the Office of Research and Development put their researchers and techs to work. The bug itself would take serious tinkering: it needed a microphone, battery, transmitter, and antenna—and because it was the 1960s, it couldn’t exactly be a short one. Everything would have to be hidden either on or inside of the cat to avoid discovery and tampering (by humans or the cat itself)!

Researchers tested each component on dummies and then live cats, recording their reaction to the “foreign materials.” They came up with a surgically implanted audio system: an inch-long transmitter at the base of the cat’s skull, a microphone in its ear canal, small batteries inside its rib cage, and a fine antenna wire woven into the cat’s fur along its spine to its tail. Every element was wrapped in specially developed packaging that could survive “the temperature, fluids, chemistry, and humidity of the body.” 3

Now that the CIA had developed a bionic cat, the problem was getting it to obey commands to walk in desired directions and listen to targets. None of the officers on the project must have owned a cat, because as any owner will tell you: “trained cat” is a bit of an oxymoron. Cats do as they please, and it is your good fortune if their whims coincide with your needs. Nonetheless, the training program proceeded.

The Agency researchers put the cats through daily programs that tested their “attention span, physical endurance [and] total range” while increasing the “complexity and skill level” of their environment. They would guide the cats by playing audio cues in their ear: one tone for “left,” another for “right,” and so on.4 In a lab setting, they proved that they could indeed guide the cats short distances to targets.

Unfortunately, the cats did not fare so well on longer, more complex tasks. Cats would “walk off the job” whenever they got hungry or bored, ignoring all instruction or pleading as cats are wont to do. To correct this, the techs “put another wire in to override” their sense of hunger. Victor Marchetti, who served as executive assistant to the Director at the time, was not surprised by the arduous testing process. “They made a monstrosity,” he told reporters later. “They tested him and tested him.”5

After five years of tinkering, testing and training, the moment of truth arrived in 1966: the acoustic kitty’s first field test. The mission would be easy, low-stakes; the first step towards the Agency’s ultimate goal of releasing a bugged cat into the Soviet embassy. For now, all the cat would have to do was saunter up to two civilians sitting on a park bench and sit patiently while agents listened in.6

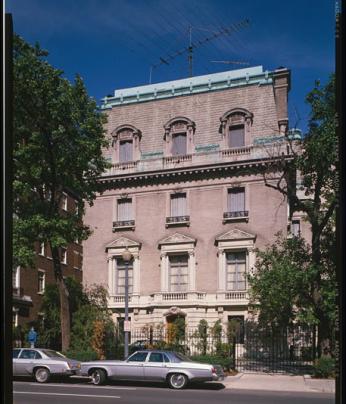

A couple of agents loaded into a van filled with monitoring instruments, switches, and dials. They drove their high-tech cat in the direction of the old Soviet Embassy (today’s Pullman House) on Sixteenth Street, a square-faced Beaux Arts building. They parked their van a few blocks from the Embassy on Lafayette Square and went through the cat’s final preparation, checking their instruments and radio receivers.

What happened next is unclear, but the prevailing story comes from Victor Marchetti, and it is a picture of irony:

“Finally, they’re ready. They took it out to a park and pointed it at a park bench and said, ‘Listen to those two guys.’” Parked on one side of the street, the agents carefully lower the very expensive cat out of the van. It takes in its surroundings in the unbothered, imperious way cats do: the bustling street, the soft grass in the park, the open sky. It probably begins hearing soft beeping: the audio cues directing it forward, across the street to its unwitting targets.

Then, before it can take more than a few steps, a taxi peels down the street—and runs him over.

“There they were,” Marchetti said of the probably horrified agents, “Sitting in the van with all those dials, and the cat was dead!”7

A cat, mind you, which was wired with classified CIA technology and had cost between $10 and $20 million over years of research.8 Not exactly the report you want to bring back to headquarters. But that report might not have been made at all: the principal on the project disputed that the cat was hit on its first day, saying the project was too “serious” for such an ignominious end.9

Even if the cat wasn’t run over, it’s doubtful that it would have survived very long with a battery and wires in its stomach. The fact that the CIA could pick up audio from the cat at all was “a medical success,” but implementing the project was “an operational disaster.”10

An interview with the former director of the Office of Technical Service, Robert Wallace, offers a happier ending for the Acoustic Kitty. When the project was abandoned due to the impossibility of training the cats, “the equipment was taken out… the cat was re-sewn for a second time, and lived a long and happy life afterwards.”11

Because the operation hasn’t been fully declassified yet, it’s impossible to know what really happened that day in DC. But you can guess that the CIA learned their lesson. The only declassified document mentioning the project by name is a final evaluation from 1967 thrillingly titled: Views on Trained Cats [redacted] for [redacted] Use.

“We have satisfied ourselves,” it said. “Cats can indeed be trained to move short distances.” This, as any cat owner could probably attest, is indeed an impressive achievement. The researchers saw “no reason” that cats could not “be similarly trained” for other tasks. However, “environmental and security factors in using this technique in a real foreign situation force us to conclude that… it would not be practical.”12 Project Acoustic Kitty, after five years and fifteen million dollars, was closed.

Another memorandum circulated after a meeting with the executive director of “Animal Projects” to discuss the future of “bird and cat” programs. While the “technical achievements” of such programs were “of the highest order,” the director decided that their practical uses were “minimal” and he “could not justify the expenditure of substantial funds” for more cat training.13

The Animal Projects team continued investigating the feasibility of using dogs, dolphins, ravens, cows, and pigeons for espionage through the 1970s. It also did not entirely give up on the question of cats. In 1969, there was still mention of “operational evaluation” of cats “as an audio surveillance vehicle.”14

The administration, though, was now less amenable to the idea. That same year, an executive director wrote cautiously, “I have no objection to a modest expenditure” for cat-related endeavors, but he would “like to know more specifically… and how much money is going into the effort before it is undertaken.”15

In a blunter memo, maybe he would have written: We learned years ago that cats cannot and do not want to be trained. Please do not waste more money or time proving what we already know: dogs have masters; cats have staff.

Footnotes

- 1 Richelson, Jeffrey T. The Wizards Of Langley: Inside The Cia’s Directorate Of Science And Technology. Basic Books, 2008.

- 2

Vanderbilt, Tom. “The CIA’s Most Highly-Trained Spies Weren’t Even Human.” Smithsonian Magazine, September 30, 2013.

- 3 Wallace, Robert, H. Keith Melton, and Henry R. Schlesinger. Spycraft: The Secret History of the CIA’s Spytechs, from Communism to Al-Qaeda. Penguin, 2009.

- 4

Central Intelligence Agency. Behavioral Program. # C00022016. CIA, 1968.

- 5

Jones, Nate. “Document Friday: Acoustic Kitty.” UNREDACTED, March 5, 2010.

- 6 Curtis, Adam, "You Have Used Me as a Fish Long Enough", The Living Dead, BBC television documentary, 1995, interview with Victor Marchetti at 28:10

- 7 Richelson, Jeffrey T. The Wizards Of Langley: Inside The Cia’s Directorate Of Science And Technology. Basic Books, 2008.

- 8

Stephens, Robert. “CIA Recruited Cat to Bug Russians.” The Telegraph, November 4, 2001.

- 9

Vanderbilt, Tom. “The CIA’s Most Highly-Trained Spies Weren’t Even Human.” Smithsonian Magazine, September 30, 2013.

- 10

National Security Archive. “In Memoriam: Jeffrey T. Richelson, 1949-2017,” November 14, 2017.

- 11 TV series "The World's Weirdest Weapons", season 1, episode 6: "Weapons Of The Superspies", Yesterday TV

- 12

Central Intelligence Agency. [REDACTED] Views on Trained Cats [REDACTED] for [REDACTED] Use. Doc. ID # 21897:21897. CIA, 1967.

- 13

Central Intelligence Agency. Meeting with the Executive Director on the Animal Projects. # C06636805. CIA, 1967.

- 14

Central Intelligence Agency. Meeting with the Executive Director on the Animal Projects. # C02379696. CIA, 1969.

- 15

Central Intelligence Agency. Memorandum on Animal Studies Projects. # C02379709. CIA, 1969.

![Small Arms Practice Six OSS recruits watch an instructor shoot a small arm during training at Chopawamsic's Area C. [Source: National Park Service]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2A8CB9F8-1DD8-B71C-070E22100840145DOriginal.jpg?itok=xboGo_08)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)