Pioneering D.C. Artist Inez Demonet Helped WWI Soldiers Put Their Lives Back Together

“By days she paints gruesome pictures of the insides of rats so newly dead their bodies still glow faintly with animal heat. By night she does exquisite etchings of a Chinese junk idling down the Yangtze, of the flower market at Rouen, of the Lincoln Memorial with the moon’s sheen above it.”1

It’s a bit of an odd opening for an artist’s profile, even if the concept of an artist with a “double life” won’t seem strange to other creative people who need to pay the bills. But the Washington-based artist Inez M. Demonet, whom The Washington Post called a “strange, Jekyll and Hyde sort of artist,” seemed to enjoy the local press’s fascination with her day job.2 Though she specialized in etchings and watercolors of District landmarks and people, she spent most of her time in an office at the National Institute of Health, where she worked as a medical illustrator. “It is from the rats I make my living,” she joked to the Post in 1934, showing them her latest work: a series of illustrations showing diseased rats, intended to aid public health professionals in identifying infections that can spread to humans.[3

But while her work—and, indeed, her life—is treated as a fun oddity in the various newspaper profiles made throughout her lifetime, Demonet’s landmark career as a medical illustrator is never fully celebrated. When she began her career at the NIH in 1926, she was the sole artist on staff—by 1938 and until her retirement in 1965, she was the chief of the entire new Medical Arts Division.4 Her work helped to educate doctors and public health professionals, and even helped repair the lives of soldiers returning from World War I. She also served as an example for other artists in the area—that work and passions can coexist.

A District native, Inez Michon Demonet was born in Washington in 1897 and attended the Corcoran School of Art, where her achievements in watercolors made her a star pupil.5 Her career as a medical illustrator began shortly thereafter, when the United States entered World War I in 1917. Demonet contributed to the war effort in a unique way: knowing her talents, her friends in the military got her a job at Walter Reed Medical Center in Bethesda, where she assisted doctors with facial reconstruction surgeries. Some of her earliest medical works are beautifully detailed sketches of these surgeries, showing the processes step-by-step, allowing other surgeons to copy the techniques. Some of the men who returned from the European trenches bore horrific injuries, the sight of which took some getting used to. As Demonet later recounted to the Post:

“I guess I was pretty much of a nuisance at first. The doctors had to spend almost as much time with me as with the patient. But, after I’d been carried out of the room a few times, I made up my mind I’d have to get over my squeamishness. I did it by learning to anticipate the next move of the surgeon. This kept me so entertained I forgot to become woozy.”6

Demonet was also learning that medical illustration was a combination of art and science. By observing the surgeries and developing a keen understanding of the human body, Demonet was able to notice and anticipate the kinds of details that medical professionals needed to see. Nowadays, according to the Association of Medical Illustrators, these artists understand the unique nature of their field and receive training in medicine, science, art, design, visual technology, and in theories related to communication and education.7 In 1917, though, Demonet—and lots of other female artists employed during wartime—were having to pioneer the field themselves.

After the end of the war, Demonet was released from her work at Walter Reed. But having gained the experience with medical illustration, as well as a taste for the paychecks she earned with a full-time job, she was interested in pursuing the career further. She spent some time studying at the School of Industrial Art and Technical Design for Women, a vocational school in New York City, where she perfected her skills. In 1926, a friend happened to notice a job opening at the National Institute of Health, so Demonet jumped at the chance.8

Of course, as she herself noted to the Post, Demonet’s gender made it harder to get the job she wanted so desperately. 200 applicants underwent a qualifying examination for the job, which whittled the search down to two real candidates: Demonet and a man from the Department of Agriculture. Even though her exam grade was higher, she faced losing the position, since the NIH “wanted a man artist.”9 She believed that her wartime experience at Walter Reed “decided things in her favor,” and she was eventually offered the position.10

During her career, Demonet became used to bizarre and often upsetting sights. At first, she painted human anatomy—the injuries and illnesses of those who, like the World War I soldiers, were suffering horrifically. The “most gruesome” subject, she recounted, was the heart and lung of a mine worker. “He had spent years—most of his life—in the mines,” she told the Post. “His heart and lung were black with coal dust.”11 She also painted close-ups of microscope slides—the microbes that cause the diseases that she and the NIH staff studied. Eventually, she moved to the animal subjects that inspired such curiosity in her community: rats, monkeys, rabbits, guinea pigs, mice, even a parrot sick with psittacosis. “And while my stomach no longer plops into my throat at the sight of one of them split wide open…I certainly don’t sit and gaze at [them], lost in the beauty of it all,” she told the Post.12 Though not beautiful in the traditional sense, Demonet’s work was exhibited and lauded within the medical world. Her work was collected into shows and she won two gold medals—for her work on the diseases tularemia and Rocky Mountain spotted fever.13

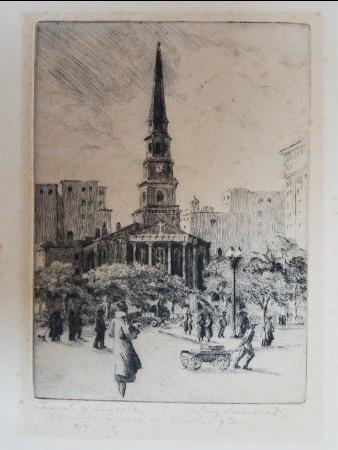

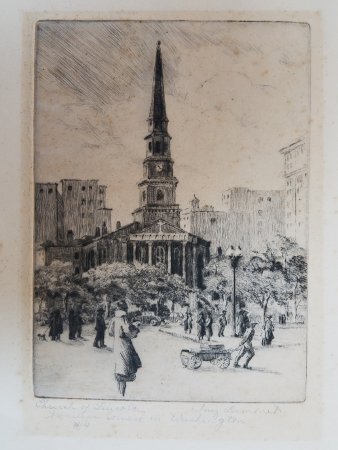

On the side, though, Demonet continued to grow as a landscape artist—her true passion. “Someday I hope I’ll be able to give my time to etching,” she told the Post, the medium she began to experiment with in the 1930s. At her first exhibition of etchings, held at the Corcoran in 1933, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt bought one of her pieces: a view of the Washington Monument.14 Thereafter, her work was celebrated and often showcased in the local Washington artistic community. She was never able to give up her day job at the NIH and focus on her other art, but was happy that she could still find success in her hobby. She was “proof that a woman can hold a full-time job and do creative work as a sideline,” one Post article reported.15

Again, this may not seem such a novel concept to us in 2024, where “side gigs” are a regular thing, but Demonet was clearly proud of the way her career might influence other artists in her hometown: “I’ll admit it’s not easy to put in a full day here making scientific drawings and then go home and work some more,” she told journalists, when asked how she finds the time to keep her passion for etching alive. “Yet I’m convinced you can generally find time to do anything if you really want to. The trick lies in making yourself start.”16

Today, Demonet isn’t well-remembered, even in the hometown she so adored, but some of her works are held by local museums, including the Smithsonian’s American Art Museum. She’s better known within the professional field she championed, where an annual scholarship from the Association of Medical Illustrators honors her.17 But it seems apt to remember her as someone who, through unconventional means, found a way to turn her talents into a trailblazing career—all while keeping her real passions alive. Though her accomplishments are largely forgotten in an age of digital imagery, her hard work and commitment to Washington arts should be celebrated.

Footnotes

- 1 Virginia Lee Warren, “Jekyll and Hyde Artist Paints Rats and Etches,” The Washington Post (Washington, D.C., 20 August 1934), page 12.

- 2 Ibid.

- 3 Ibid.

- 4

Michele Lyons, “What’s New in the NIH Archives,” I Am Intramural Blog (2 January 2019).

- 5 “Wins Gold Art Medal,” The Washington Post (Washington, D.C., 27 May 1915), page 5.

- 6 Warren, “Jekyll and Hyde Artist Paints Rats and Etches.”

- 7

“Enter the Profession,” the Association of Medical Illustrators.

- 8 Warren, “Jekyll and Hyde Artist Paints Rats and Etches.”

- 9 Ibid.

- 10 Ibid.

- 11 Ibid.

- 12 Ibid.

- 13 Ibid.

- 14 “Woman Artist Finds ‘Amazing’ Beauty in Germs She Draws for Doctors,” The Washington Times (Washington, D.C., 7 September 1933), page 19.

- 15 Hope Ridings Miller, “Inez Demonet Finds Avocation is Spice of Life,” The Washington Post (Washington, D.C., 1 January 1936), page 11.

- 16 Ibid.

- 17

“Scholarships,” the Association of Medical Illustrators.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)