Riot Grrrl: A Feminist Revolution in D.C.'s Punk Scene

This article contains explicit language and brief discussions of sexual assault.

To listen to D.C.'s Riot Grrrl bands, check out D.C. Grrrls to The Front on Spotify.

In a grainy concert video, the Capitol building rises behind a handmade sign that reads “TURN OFF YOUR TV.” In front of it, punk musician Kathleen Hanna calls out to a crowd.

"We’re Bikini Kill. We're from Washington, D.C,” she says, adjusting her mic. "The more girls up front, the better. And if anybody is fucking with you at this show, and you need to come up for certain reasons, come up front, and sit on the stage. And get away from them and let us know."1

The band launches into their song, “Girl Soldier:” "Guess you didn't notice/While we were crying/Guess you didn’t care/Only women were dying."

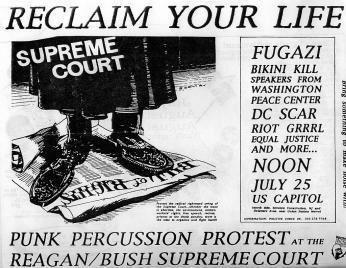

Headlined by Bikini Kill and Fugazi, organized in protest of the “radical rightward swing of the Supreme Court,” the 1992 concert captured the ethos of a national music movement reaching its peak: Riot Grrrl.2 Explicitly D.C. and DIY, Riot Grrrl spread nationwide through hand drawn zines and photocopied posters. Young-woman-fronted bands wrote songs about girlhood, political resistance, and the misogynistic constraints of the late-1980s punk scene from which they emerged, taking on musical influence while rebelling against a violent, sexist contingent of punk’s fanbase. 3

By the late 1980s, the D.C. punk scene had changed significantly on the heels of 1985’s Revolution Summer, focused on protest and political change. Women like Sharon Cheslow made space in the scene by forming D.C.’s first all-female punk band, Chalk Circle.4

But as women pushed to advance the community, shows became increasingly more intense, fans more aggressive, and overall, it was “a pretty manly, violent mess.”5

“A lot of people were driven away [from the D.C. Hardcore scene] in the early to mid-80s by the violence,” recalled Ian MacKaye, Fugazi frontman. “Particularly, I think women, they moved away from the front of the stage and eventually they left the room.”6

“Some punk shows are really gross, because the girls always get pushed to the back,” said Allison Wolfe, vocalist of Riot Grrrl band Bratmobile, in 1990. “And it’s this sweaty boy, long hair, beer belly thing in the front. It’s just really annoying. It’s like, girls need to reclaim the scene for themselves, I think."7

The roots of the Riot Grrrl movement, which would soon change the music scene of D.C., initially emerged across the country in Olympia, Washington.

In the fall of 1990, Kathleen Hanna and Tobi Vail, students at The Evergreen State College in Olympia, formed a band, calling it Bikini Kill. Hanna had spent part of her childhood in D.C., and so Bikini Kill made connections with other artists in the District’s well-known punk scene. Other Pacific Northwest bands had similar connections to the DMV.

D.C. soon became a popular place for West Coast musicians to visit, and, in some cases, settle. Many bands made use of the resources available at their childhood homes (or those of friends), parents’ offices, and the young, collaborative nature of the D.C. scene. 8, 9

“I wanted to start a magazine,” Hanna said, “or some sort of project. And I was moving to D.C., and I didn't really want to start one if there weren't women in D.C. who were interested."10

There were.

Bikini Kill’s girls-to-the-front message energized fans, and their move to D.C. is often cited as Riot Grrrl’s East Coast genesis, with Hanna hailed as the genre’s founder.11 But in truth, the Washington scene was far more collaborative than any single-band origin story.

“Riot Grrrl started, to my recollection, with Allison Wolfe and Molly Neuman [of Bratmobile],” Hanna remembered. “They made a fanzine called Riot Grrrl and a bunch of us wrote for it.”12

Other musicians recalled the movement beginning even earlier.

“Riot Grrrl was forming in DC in 1991,” asserted Christina Billotte, D.C.-native and guitarist of Slant 6. “There had been riots in DC in our neighborhood that spring when a police officer shot and wounded a Salvadoran man in Mount Pleasant. As I remember, I was sitting at the base of the steps in The Embassy. I heard Jen Smith [of Bratmobile] exclaim from the second-floor hall, ‘girl riot!’ and then someone from one of the bedrooms said, ‘Riot Girl!’ and the name was coined.”13

The Embassy was a “punk house in Mount Pleasant,” and a center of the early 90s Hardcore scene in Washington.14 Places like The Embassy and the Positive Force House in Arlington weren’t just homes for D.C. punk musicians, but for D.C. punk activism, and their collaborative communities fed Riot Grrrl’s rise.15

Riot Grrrl, the weekly zine published by members of Bratmobile and Bikini Kill, spread the movement further. The zine featured D.C. punk news and essays about topics like assault, reproductive justice, and intersectionality, printed in-between playlists, collages, and inside jokes about “kiss and ride” Metro signs.

The first issue, published in the summer of 1991, signs off with an Irving Street mailing address and a call for community submissions: "we don't know all that many angry grrrls, although we know you are out there. here is the perfect time to get out & scream if you wanna!”16

An excerpt of “The Riot Grrrl Manifesto,” published in the zine’s second issue, reads:

“BECAUSE we know that life is much more than physical survival and are patently aware that the punk rock ‘you can do anything’ idea is crucial to the coming angry grrrl rock revolution which seeks to save the psychic and cultural lives of girls and women everywhere, according to their own terms, not ours.

BECAUSE we are interested in creating non-hierarchical ways of being AND making music, friends, and scenes based on communication + understanding, instead of competition + good/bad categorizations.

BECAUSE doing/reading/seeing/hearing cool things that validate and challenge us can help us gain the strength and sense of community that we need in order to figure out how bullshit like racism, able-bodieism, ageism, speciesism, classism, thinism, sexism, anti-semitism and heterosexism figures in our own lives.”17

The movement was by girls, for girls, forcing detractors to get in or get out of the way.

In a matter of months, Riot Grrrl exploded.

Locals in the DMV and Olympia, Washington made their own fanzines to distribute among fellow Riot Grrrls. Kathleen Hanna, along with other D.C. organizers, held meetings for young women in the city “to help each other learn to play instruments + get stuff done.”18 Bands, fans, and readers cropped up in cities across the country.19

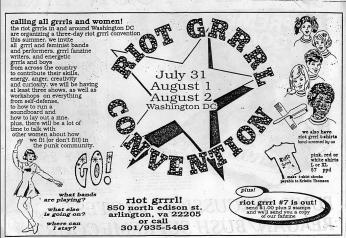

After a year of growth, Kathleen Hanna organized the Riot Grrrl Convention in August 1992. The three-day festival in D.C. highlighted local and national bands with “workshops on everything from self-defense, to how to run a soundboard and how to lay out a zine. plus…a lot of time to talk with other women about how we fit (or don’t fit!) in the punk community.”20

A girl-dominated punk future was possible.

“It felt like everything was changing,” reflected Allison Wolfe, “like in the social landscape, at least in our world, girls were just taking over the punk rock scene.”21

But Riot Grrrl’s rise from tight-knit community to national sensation was not something its members had prepared for. After the success of the Riot Grrrl Convention, the small DIY scene was flooded with reporters attempting to capture the movement.

“It was overwhelming to see your friends all of a sudden in magazines and seeing the whole world looking,” said Allison Wolfe. “People coming in and trying to characterize everything and ending up making caricatures out of everyone.”22

The inaccurate portrayals of Riot Grrrl as a club of irrational teenagers, or as heralding a generic, toothless, “girl power” message, sparked a widespread protest from scene members.

“I was in Riot Grrrl when we had this media blackout; we hated the media because they didn’t get it and they weren’t representing us and they were exploiting us,” insisted Wolfe. “They were making us look really stupid and turning us into a fashion trend. So we decided, ‘We’re trying to represent ourselves here. So we don’t need you.’”23

While the mainstream media chipped away at Riot Grrrl’s image, the movement also succumbed to its internal flaws.

“I started inkling like, a year into it,” said Ramdasha Bikceem, musician and editor of Gunk zine. “I started feeling funny about it…it was just a weird position to be in, a lot of times being the only person of color there and feeling like nobody gave a shit…This was an empowering movement for them, and it was really only relative to a White, middle class punk girl… it was extremely frustrating to start realizing that and start being like, these aren't my people.”24

By the mid-1990s, Riot Grrrl’s spark fizzled out. Bands split, core messages twisted, and new musicians rose to fill the gap it left.25 Among them were movements like Sista Grrrl Riot in New York City, which was explicitly created to celebrate Black women in punk.26

The Riot Grrrl movement was short lived, and arguably short sighted, but its impact on punk music, let alone the D.C. scene, was massive.

“It changed me. I’m speaking as a man, I’m speaking as a man who was in his thirties when this happened,” reflected Mark Andersen, D.C. punk historian and co-founder of Positive Force House. “Imagine what it must have done for the people, for the girls who were in their teens, who suddenly came to believe that the drama of punk was their drama. In fact, that the drama of life was their drama.”27

“I’d say Riot Grrrl was about a lot more than just girls playing rock,” said Christina Billotte of Slant 6. “When Bikini Kill moved to DC, they changed the dynamic, and it felt like the scene was women dominated for the year or so they were there. The ‘Girls to the front!’ thing really was important because it was bringing awareness to the fact that the scene belonged to women too, and they didn’t have to watch shows from the side or the back or get pushed around.”

But ultimately, Billotte conceded, “I think a lot more women play music now than when I was starting out. But racism and sexism are always there, covertly and overtly.”28

Want to hear the revolution? Check out “D.C. Grrrls to the Front,” a playlist of Riot Grrrl bands, their influences, and the local musicians they inspired in the 30 years since the movement began in Washington, D.C.

Footnotes

- 1

Bikini Kill Wdc 1992, 2007.

- 2

RockCreek. File:Riot Grrrl Convention 1992 by Rockcreek.Jpg. January 15, 2014.

- 3

Hannon, Sharon M. “A RIOT GRRRL PRIMER: REVOLUTION GIRL STYLE NOW.” PleaseKillMe, April 2, 2020.

- 4

Hannon, Sharon M. “PUNK ROCK WAS NOT A BOYS’ CLUB.” PleaseKillMe, November 2, 2017.

- 5

Davidson, Eric. “SLANT 6: STRAIGHT OUTTA WASHINGTON, D.C. IN THE ’90S.” PleaseKillMe, July 13, 2020.

- 6

Don’t Need You - The Herstory of Riot Grrrl. Urban Cowgirl Productions, 2012

- 7

Don’t Need You - The Herstory of Riot Grrrl. Urban Cowgirl Productions, 2012

- 8

Crane, Robin. “ALLISON WOLFE: ROOTS OF THE RIOT GRRRL MOVEMENT.” PleaseKillMe, February 20, 2019.

- 9

Hannon, Sharon M. “A RIOT GRRRL PRIMER: REVOLUTION GIRL STYLE NOW.” PleaseKillMe, April 2, 2020.

- 10

Don’t Need You - The Herstory of Riot Grrrl. Urban Cowgirl Productions, 2012

- 11

Hannon, Sharon M. “A RIOT GRRRL PRIMER: REVOLUTION GIRL STYLE NOW.” PleaseKillMe, April 2, 2020.

- 12

Don’t Need You - The Herstory of Riot Grrrl. Urban Cowgirl Productions, 2012

- 13

Davidson, Eric. “SLANT 6: STRAIGHT OUTTA WASHINGTON, D.C. IN THE ’90S.” PleaseKillMe, July 13, 2020.

- 14

Crane, Robin. “ALLISON WOLFE: ROOTS OF THE RIOT GRRRL MOVEMENT.” PleaseKillMe, February 20, 2019.

- 15

“Positive Force DC.” Accessed July 26, 2024.

- 16

Riot grrrl. Melissa Klein Collection. DC Punk Archive. Accessed August 6, 2024.

- 17

Riot Grrrl Archive. “RIOT GRRRL MANIFESTO.” Accessed August 6, 2024.

- 18

Riot Grrrl, Number 3. Melissa Klein Collection. DC Punk Archive. Accessed August 6, 2024.

- 19

Riot Grrrl!, .Melissa Klein Collection. DC Punk Archive. Accessed August 6, 2024.

- 20

Rockcreek. File:Riot Grrrl Convention 1992 by Rockcreek 2.Jpg. January 15, 2014.

- 21

Don’t Need You - The Herstory of Riot Grrrl. Urban Cowgirl Productions, 2012

- 22

Don’t Need You - The Herstory of Riot Grrrl. Urban Cowgirl Productions, 2012

- 23

Crane, Robin. “ALLISON WOLFE: ROOTS OF THE RIOT GRRRL MOVEMENT.” PleaseKillMe, February 20, 2019.

- 24

Don’t Need You - The Herstory of Riot Grrrl. Urban Cowgirl Productions, 2012

- 25

Hannon, Sharon M. “A RIOT GRRRL PRIMER: REVOLUTION GIRL STYLE NOW.” PleaseKillMe, April 2, 2020.

- 26

Bess, Gabby. “Alternatives to Alternatives: The Black Grrrls Riot Ignored.” Vice (blog), August 3, 2015.

- 27

Don’t Need You - The Herstory of Riot Grrrl. Urban Cowgirl Productions, 2012

- 28

Davidson, Eric. “SLANT 6: STRAIGHT OUTTA WASHINGTON, D.C. IN THE ’90S.” PleaseKillMe, July 13, 2020.

Divider (basic)

Divider (fancy light)

Divider (fancy dark)

Page Header (left aligned, "white-no-image" style)

Magdalena Abakanowicz

Page Header (center aligned, "gradient-to-edge" style)

Black History

Page Header (center aligned, "gradient-to-fade" style)

Black History

Quote Component

From all this pretentiousness Seventh Street was a sweet relief. Seventh Street is the long, old, dirty street, where the ordinary Negroes hang out, folks with practically no family tree at all, folks who draw no color line between mulattoes and deep darkbrowns, folks who work hard for a living with their hands. On Seventh Street in 1924 they played the blues, ate watermelon, barbecue, and fish sandwiches, shot pool, told tall tales, looked at the dome of the Capitol and laughed out loud. I listened to their blues...

I tried to write poems like the songs they sang on Seventh Street—gay songs, because you had to be gay or die; sad songs, because you couldn’t help being sad sometimes. But gay or sad, you kept on living and you kept on going. Their songs— those of Seventh Street—had the pulse-beat of the people who keep on going. Like the waves of the sea coming one after another, always one after another, like the earth moving around the sun, night, day—night, day—night, day— forever, so is the undertow of black music with its rhythm that never betrays you, its strength like the beat of the human heart, its humor, and its rooted power.

Langston Hughes

Teaser "default" (with an image)

Teaser "card" (with an image)

Teaser "card" (with a image and video)

CTA Default

Default CTA Example

Interdum risus tortor turpis gravida sed. Risus sit et egestas tellus ac sed. Purus ut eu fermentum non. Arcu lectus sed in quisque vitae posuere. Adipiscing nullam mauris iaculis leo turpis leo, congue.

CTA Compact

Not sure what to read? Let's pick a story for you!

CTA Featured

Post It

D.C. Architecture & Urban Planning

20 Posts

Black History in Washington

35 Posts

Civil Rights Movement

42 Posts

Historic Neighborhoods

28 Posts

Cultural Landmarks

31 Posts

Music & Arts Scene

17 Posts

Political History

54 Posts

Local Stories & People

23 Posts

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)