“A Deafening Roar”: How Washington Celebrated Its First World Series Win in 1924

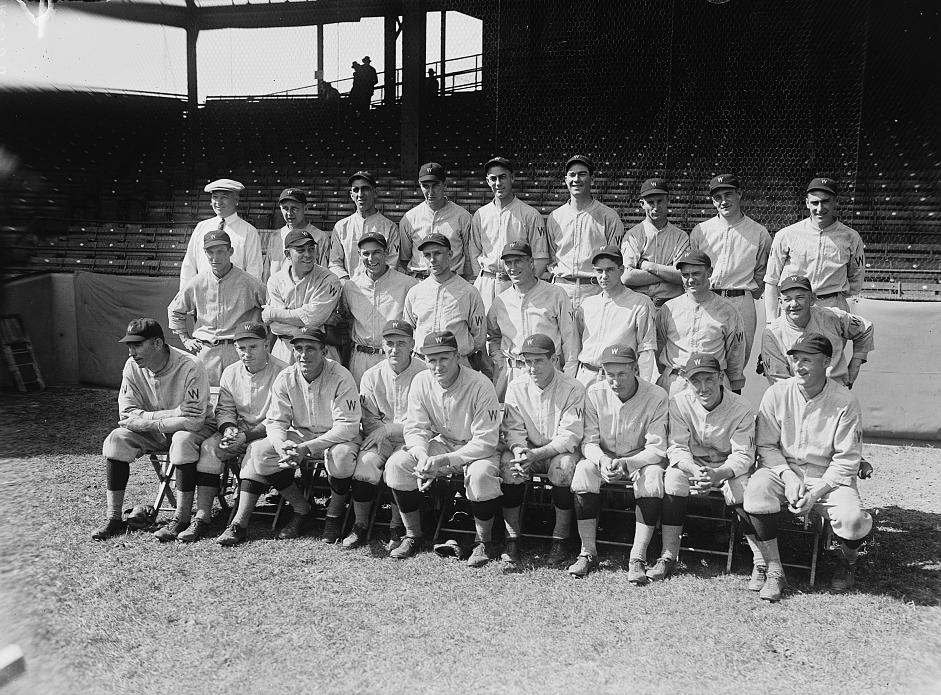

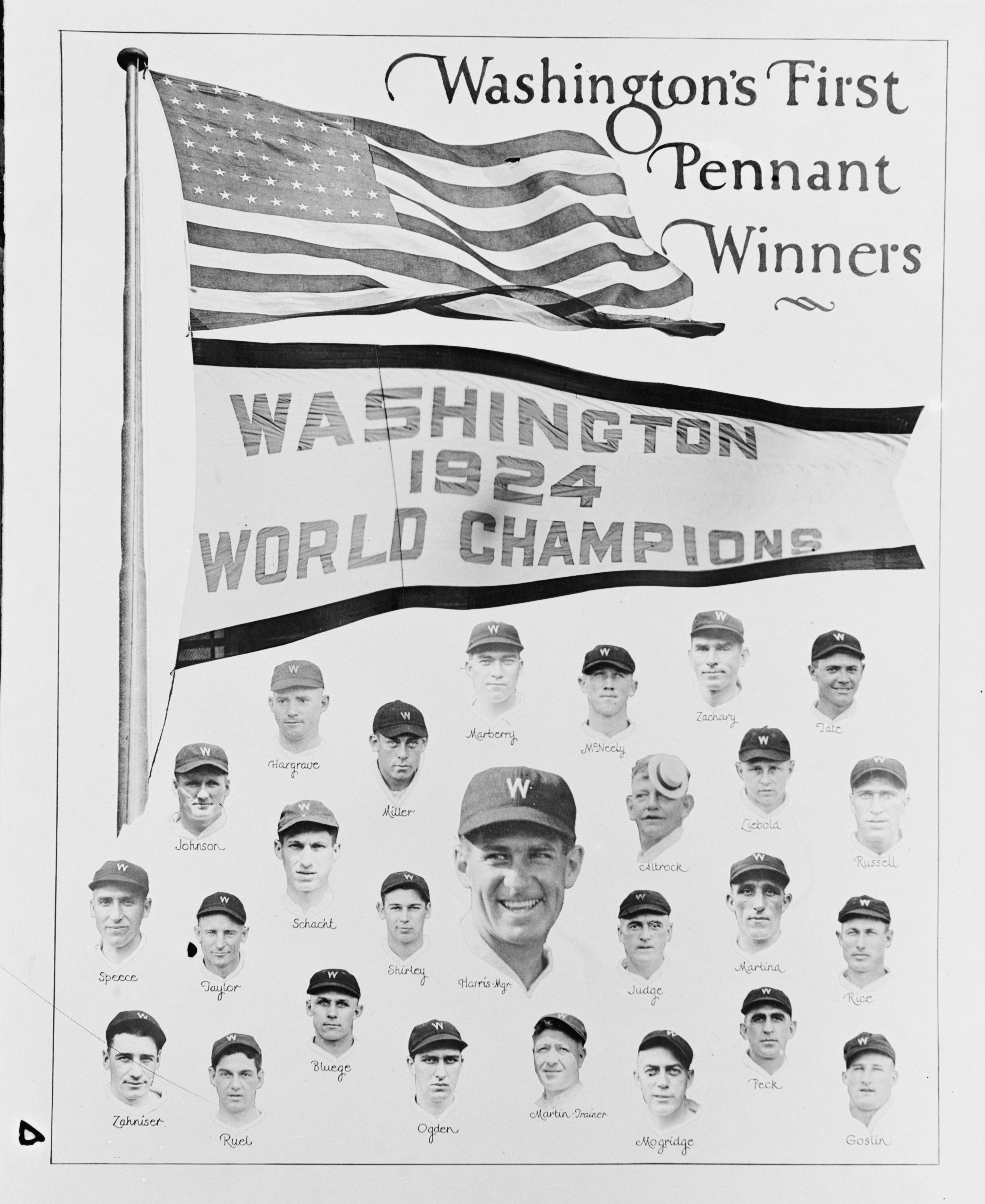

A century ago Washingtonians partied like they never had before after the unthinkable happened—the Washington Senators became World Series champions on October 10, 1924. After two decades of hopelessness and heartbreak, that year a Senators “Team of Destiny” won their first American League pennant and ticket to the Fall Classic under the leadership of 27-year-old player-manager Bucky Harris and veteran fastballer Walter Johnson.1

While their feel-good underdog story won over baseball fans everywhere, few expected the Senators to beat the powerhouse New York Giants in the best-of-seven series when it began on October 4. Up three games to two, Giants first baseman George Kelly was so confident of victory heading into Game 6 that he didn’t even pack a toothbrush as he and his teammates traveled to DC.2 But the Senators—also nicknamed the Nats, Griffs, or Griffmen (after owner Clark Griffith)—battled back like they had all season to force a deciding Game 7.

That Friday afternoon a crowd of more than 30,000, including President Calvin Coolidge, packed into Griffith Stadium between W Street and Florida Avenue NW while thousands more across town listened on radio and gathered around temporary scoreboards “where tiny electric lights or plain chalk numerals were telling the story as best they could.”3 Desperate fans bought last-minute tickets from scalpers for as high as $150—more than $2,700 in today’s dollars.4

All of Washington held its breath in the bottom of the eighth inning as manager and second baseman Harris stepped up to the plate with the bases loaded and two outs, the Senators down 3-1. “[W]hite-faced and determined,” Harris, who had smashed a one-run homer earlier in the fourth, swung at the first pitch and hit a grounder that miraculously bounced over Giants third baseman Fred Lindstrom’s head, scoring two runs and tying the ballgame.5

With the game still tied in the ninth, Walter Johnson took the mound “amid the cheers of the crowd” and redeemed his previous two series losses by pitching four scoreless innings of emergency relief.6 Then came the bottom of the twelfth. With runners on first and second, Washington center fielder Earl McNeely hit a ball down the third baseline that took yet another bad hop over Lindstrom.7 Catcher Muddy Ruel raced around third and touched home plate, winning the game—and the Senators’ long-awaited World Series title.

Hailed as the “greatest contest in the history of the game,” the Game 7 victory launched Washington into a “veritable orgie of joy,” reported Harold K. Philips of The Evening Star.8 The crowd immediately swarmed the field, with one man literally stealing third base and tucking it under his coat as a keepsake.9 Second and third base disappeared as well, and an “urchin of ten dug his finger nails valiantly under home plate, but without success.”10 Bats, balls, and even the American flag from the presidential box were looted in quick succession.11

“Of course,” the normally taciturn President Coolidge later told friends, “I am not speaking as an expert or as a historian of baseball, but I do not recollect a more exciting world series than that which has finished this afternoon.”12

Overwhelmed police officers “fought with fists and clubs to clear a lane through the mad throng” for players to return to the clubhouse, where jubilant Senators performed a war dance and hugged one another.13 Players “acting like kids at an orphanage when Santa Claus comes” huddled around Johnson to shake his hand and Harris, “nearly crazy with gladness,” forgot to put his clothes on as he emerged from the showers and began fielding questions from the press as he combed his hair.14

“I’m the happiest man in the world—the happiest man in the world,” a smiling and fully clothed Johnson told an Evening Star reporter in the dressing room.15 “Tell everybody I’m tickled to death and anything else along the same line you can think of. I’ll stand back of anything you say, as I can’t express my feelings in words at all right now. I can never thank Bucky enough for having confidence in me again after my two other failures, and I’m happy I didn’t disappoint him and my friends.”

Team owner Clark Griffith fought back tears as he praised Harris, the “impossibly” young manager he had been ridiculed for selecting to lead the team at the start of the season.16 “I’m certainly proud of you, Bucky boy,” repeated Griffith, hugging Harris “as a father would his son.”17 Griffith’s racist ownership policies ensured that not all fans could celebrate equally—although the Senators “boasted some of the country's most loyal black fans” in the 1920s, according to baseball historian Brad Snyder, they were forced to sit in the stadium’s segregated right field pavilion.18

Elsewhere, elated Washingtonians began cheering the Senators’ win with “as much noise and racket as it greeted the news of the end of the world war.”19 “The firing of small cannon, the crack of pistols, the bang of firecrackers, the honk of automobiles and the overworked lungs of half crazed baseball fans were blended into a deafening roar,” reported the Associated Press.20 Hats were tossed into the air and shredded confetti rained down from office buildings.

Revelers concentrated along Pennsylvania Avenue and F Street, between Fourteenth and Ninth Street NW, “where from sunset to long past midnight the great joyous spirit of carnival ruled with a hand that showered confetti and a sceptre of tinsel and ribbons.”21 Fans hastily made banners emblazoned with slogans like “I Told You So,” “4-3,” “Let’s Give Walter the Capitol,” and “Bucky Harris for President.”22 Everyone from government clerks to shopgirls joined in on the fun as “policemen smiled and traffic officers grinned” and the city of more than 400,000 let loose.23

Traditionally reserved Washington society seemed to have upended itself that night as “[w]omen dressed like men and men dressed like women,” including a trio of young men at F and Thirteenth Street who donned “women’s hats and trousers rolled above bare knees” and did their best to direct traffic to the amusement of onlookers.24

As The Evening Star put it, it was a “night to try men’s lungs and throats and arms and emotions, to distract traffic cops, to paralyze street car lines, to reform grouches, to break ear drums, to wreak havoc and confusion where a nation’s orderly processes of government originate.”25 Using the city’s many streetcar tracks as a race course, motorists “plowed over car-loading safety zones and between loading platforms with utter abandon,” police doing little to get in their way.26

At midnight, the festivities took a pause as a fake funeral procession carrying an effigy of Giants manager John McGraw passed through the city.27 Following their loss, the real McGraw and the rest of his team hastily boarded an overnight train to New York, arriving that Saturday in the “manner of Napoleon’s historic retreat from Moscow.”28

“I was glad that it was Johnson who beat us as long as some one had to,” said the ever-defiant McGraw.29 “I would rather have him do it than anyone I know.”

Meanwhile, having finally broken free of Griffith Stadium, Washington players began celebrating their own victory out on the town. Arriving at the Shoreham Hotel, Harris enjoyed a welcome that equaled the “reception Washington gave General John J. Pershing at this same hotel when the latter returned from across the seas after the great war.”30 Fellow Senators stars Muddy Ruel, Goose Goslin, and Curly Ogden were similarly mobbed at the Wardman Park Hotel, former headquarters of the Giants during the series, although when asked to make speeches the trio’s oratory skills “struck out ignominiously.”31

By Saturday, October 11, Washington had “quieted down somewhat,” although the press still noted some “sporadic eruptions, especially in Government buildings, business offices, restaurants, etc.”32 In those days, the Senators truly were the government’s team, as The Washington Times noted “every member of [Coolidge’s] cabinet rejoiced” and federal and district employees alike went wild.33 On Saturday a number of “over-enthusiastic fans” also appeared in Police Court to atone for their disorderly conduct the previous night.34

“I enjoyed the game as much as anybody but I didn’t go out and get drunk to celebrate the victory,” said a Judge Mattingly, who nonetheless went easy on the Senators fans, even ordering police not to rearrest one man who was still drunk as he made his way back from court.35

After all the confetti had settled, drag races had ceased, and a semblance of normalcy returned to the streets, a feeling of disbelief still seemed to linger over the city. A century later that sentiment stands, with ESPN labeling 1924’s Game 7 the “best game in baseball history” and surviving footage of the winning run continuing to inspire Nats fans today.36 But there is no understating just how much the win meant to Washington that day in that moment when Muddy Ruel crossed home plate.

“The victory of yesterday means much to Washington,” wrote The Washington Times on October 11.37 “No longer can it be said that ‘Washington is first in war, first in peace, and last in the baseball world.’ Washington is first in everything.”

Watch highlights from the 1924 World Series

Footnotes

- 1

Gary Sarnoff, Team of Destiny: Walter Johnson, Clark Griffith, Bucky Harris, and the 1924 Washington Senators (Rowman & Littlefield 2024), xiv.

- 2

Davis J. Walsh, “Chastened Giants Back in New York Accept Their Defeat Gracefully,” International News Service in The Washington Times, 11 October, 1924.

- 3

Harold K. Philips, “Capital Celebrates Bucks’ Great Victory in Joyous Delirium,”The Evening Star, 11 October, 1924.

- 4

“Senators Win World Series Four to Three,” Associated Press in The Nome Nugget, 11 October, 1924; CPI Inflation Calculator, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl?cost1=150&year1=192409&year2=202408

- 5

Harold K. Philips, “Capital Celebrates Bucks’ Great Victory in Joyous Delirium,”The Evening Star, 11 October, 1924.

- 6

“Senators Win Series,” The Kusko Times, 11 October, 1924.

- 7

Sarnoff, 189.

- 8

Harold K. Philips, “Capital Celebrates Bucks’ Great Victory in Joyous Delirium,”The Evening Star, 11 October, 1924.

- 9

“Staid Capital Forgets Dignity in Glorious Victory Celebration,”The Washington Times, 11 October, 1924.

- 10

“Staid Capital Forgets Dignity in Glorious Victory Celebration,” The Washington Times, 11 October, 1924.

- 11

“Staid Capital Forgets Dignity in Glorious Victory Celebration,”The Washington Times, 11 October, 1924.

- 12

“Jamboree in Spring is Plan Now / City Goes Wild Over World Series Victory for Griffmen,”The Washington Times, 11 October, 1924.

- 13

Harold K. Philips, “Capital Celebrates Bucks’ Great Victory in Joyous Delirium,”The Evening Star, 11 October, 1924.

- 14

“Griffs Tear Loose After Game and Celebrate Like Schoolboys,”The Evening Star, 11 October, 1924.

- 15

“Griffs Tear Loose After Game and Celebrate Like Schoolboys,”The Evening Star, 11 October, 1924.

- 16

“Griffs Tear Loose After Game and Celebrate Like Schoolboys,”The Evening Star, 11 October, 1924.

- 17

“Griffs Tear Loose After Game and Celebrate Like Schoolboys,”The Evening Star, 11 October, 1924.

- 18

Brad Snyder, “When Segregation Doomed Baseball in Washington,”The Washington Post, 15 February 2003.

- 19

“All Washington Celebrates Senators Triumph Over Giants In World Series,” Associated Press in The Americus Times-Recorder, 11 October, 1924.

- 20

“All Washington Celebrates Senators Triumph Over Giants In World Series,” Associated Press in The Americus Times-Recorder, 11 October, 1924.

- 21

“Staid Capital Forgets Dignity in Glorious Victory Celebration,”The Washington Times, 11 October, 1924.

- 22

“City Goes Insane in Carnival Spirit,”The Evening Star, 11 October, 1924; “Staid Capital Forgets Dignity in Glorious Victory Celebration,”The Washington Times, 11 October, 1924.

- 23

“Staid Capital Forgets Dignity in Glorious Victory Celebration,”The Washington Times, 11 October, 1924.

- 24

“City Goes Insane in Carnival Spirit,”The Evening Star, 11 October, 1924.

- 25

“City Goes Insane in Carnival Spirit,”The Evening Star, 11 October, 1924.

- 26

“City Goes Insane in Carnival Spirit,”The Evening Star, 11 October, 1924.

- 27

“Staid Capital Forgets Dignity in Glorious Victory Celebration,” The Washington Times, 11 October, 1924.

- 28

Davis J. Walsh, “Chastened Giants Back in New York Accept Their Defeat Gracefully,” International News Service in The Washington Times, 11 October, 1924.

- 29

Davis J. Walsh, “Chastened Giants Back in New York Accept Their Defeat Gracefully,” International News Service in The Washington Times, 11 October, 1924.

- 30

“Jamboree in Spring is Plan Now / City Goes Wild Over World Series Victory for Griffmen,” The Washington Times, 11 October, 1924.

- 31

“City Goes Insane in Carnival Spirit,”The Evening Star, 11 October, 1924.

- 32

“City Goes Insane in Carnival Spirit,”The Evening Star, 11 October, 1924.

- 33

“Jamboree in Spring is Plan Now / City Goes Wild Over World Series Victory for Griffmen,”The Washington Times, 11 October, 1924.

- 34

“Backwash of Celebration in Court,”The Washington Times, 11 October, 2024.

- 35

“Backwash of Celebration in Court,”The Washington Times, 11 October, 2024.

- 36

Sam Miller, “Ranking every World Series in MLB history,” 30 October, 2020. https://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/29104085/ranking-every-world-series-mlb-history#17

- 37

“Jamboree in Spring is Plan Now / City Goes Wild Over World Series Victory for Griffmen,”The Washington Times, 11 October, 1924.

>

>