Title IX: The Push for Gender Equality in Education Started with Bernice Sandler at the University of Maryland

Did you know that gender discrimination in education has only been illegal for just over 50 years? In 1972, colleges and universities across the U.S. were suddenly required to follow new standards if they wanted to keep receiving federal funding. That was all thanks to Title IX, a law that transformed how we think about gender equality in education.

When Congress passed the 1972 Title IX of the Education Amendments, it specifically read, “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from the participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”1 Title IX was a huge victory for women’s rights activists, but it didn’t happen overnight.

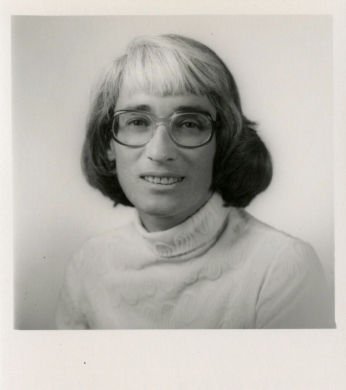

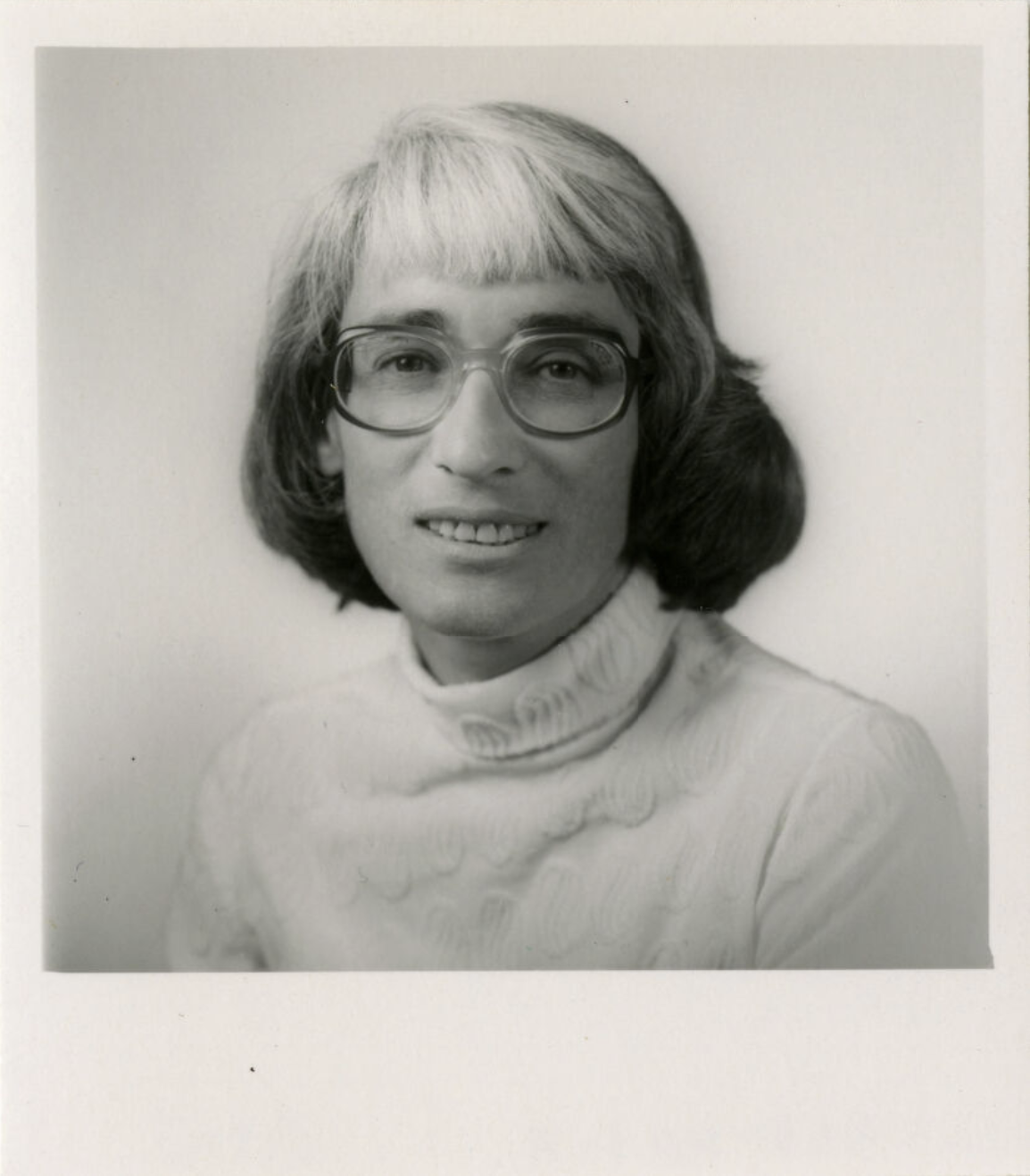

Bernice "Bunny" Sandler, often called the “godmother of Title IX,” was a key figure in pushing for this change. Funny enough, Bernice didn’t see herself as a feminist at first.2 As she wrote in one article for the National Association for Women in Education, “Like many women at that time, I was somewhat ambivalent about the women’s movement and halfway believed the press descriptions of its supporters as ‘abrasive,’ ‘man-hating,’ ‘radical,’ and ‘unfeminine.’”3

But everything changed when she faced gender discrimination in her own career.

In the late 1960s, Bernice lived in Silver Spring, Maryland, while working a part-time teaching gig at the University of Maryland, College Park.4 She lectured in psychology and counseling as part of the Psychology Department while earning her PhD in Counseling and Personnel services from the University’s College of Education.5

In 1969, there were seven openings in her department. Given her qualifications and current teaching position in the department, Sandler applied for a job that she was qualified for – a full-time, tenure track teaching position. She was soon rejected.6

When she inquired about her application and why, out of seven open positions, she hadn’t been considered for one, a faculty member responded that her chances were slim because, “let’s face it, you come on too strong for a woman.”7 That line stuck with her. She wasn’t just being told she wasn’t the right fit for the job; she was being told that her gender was the problem.8 Bernice applied to two more jobs in the area and received two more rejections. One interviewer said that she was “just a housewife who went back to school,” and the other said that he worried about hiring her in case her children got sick and needed her to stay home.9

Bernice’s husband finally called this what it was: sex discrimination. So, Bernice began her own investigation of the University of Maryland and its hiring practices.10 She looked into the demographics of 15 departments across campus, and found that within those fifteen, 57% of the instructors were women. However, more than half of the 15 departments had no female full professors at all, and none had female department heads.11 Bernice concluded that the senior positions were intentionally hiring fewer women.

Bernice soon realized that the problem wasn’t just with the University of Maryland. In fact, hundreds of universities had the exact same issues — women struggled to secure full-time, tenure track, senior positions despite their qualifications.12 ‘‘We have been limited by universities and businesses reasoning that if we are single, then we will get married and drop out. If we are married, they think we will have children. If we already have children, they think we should stay home and take care of them. And if we do wait until they grow up, we’re too old to work.”13

Frustrated, Bernice continued digging. “Knowing that sex discrimination was immoral, I assumed it would also be illegal,” she wrote later.14 She looked at racial discrimination first, analyzing Title VI of the Civil Rights Act to see about its compliance within university systems. She noted that Title VI, which prohibited racial discrimination in places receiving federal funding, specifically excluded sex discrimination. It wasn’t until she stumbled upon LBJ’s Executive Order 11246, which prohibited federal contractors from discrimination, that she found what she was looking for.15 “Eureka! There it was, a footnote saying that in October 1968, the order had been amended to bar discrimination because of sex.” Universities and colleges across the country had contracts with the government, which meant this executive order applied to those institutions as well.16 Sandler took this footnote and ran with it — she had found the legal foundation to fight back.

With the help of the Women’s Equity Action League (WEAL), Bernice filed a major complaint in January 1970. WEAL and Sandler filed an 80-page document with the Department of Labor, “charging an ‘industry-wide’ pattern of sex discrimination in higher education.” Nearly 250 more complaints against specific institutions followed, alongside a class action against all medical schools.17

Sandler began working alongside Rep. Patsy Mink (one of Title IX’s co-authors) and Senator Birch Bayh.18 She joined Rep. Edith Green’s special subcommittee on education as an education specialist, compiling a record to fight Congress’s erasure of women in education from the Civil Rights Act. She collected data from women across the country about their experiences with discrimination in higher education, specifically in terms of hiring and promotion.19

After nearly two years of legislative action, Title IX passed through Congress on June 23, 1972, and President Nixon signed it into law on July 1.20 It rolled out slowly at first, with such low press coverage that Sandler claimed to only remember “one or two sentences in the Washington papers.”21 The U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) then undertook to investigate campuses charged with sex discrimination. Title IX was officially pushed onto universities in 1975 when the Ford administration gave campuses 3 years (until 1978) to fully comply at risk of losing their federal funding.22

Title IX has since been described as the “legislative equivalent of a Swiss army knife.”23 It began to affect layers upon layers of life at universities and colleges across the country. It served as umbrella legislation to combat sexual assault on college campuses, discriminatory hiring practices, inequality in athletics, and more.

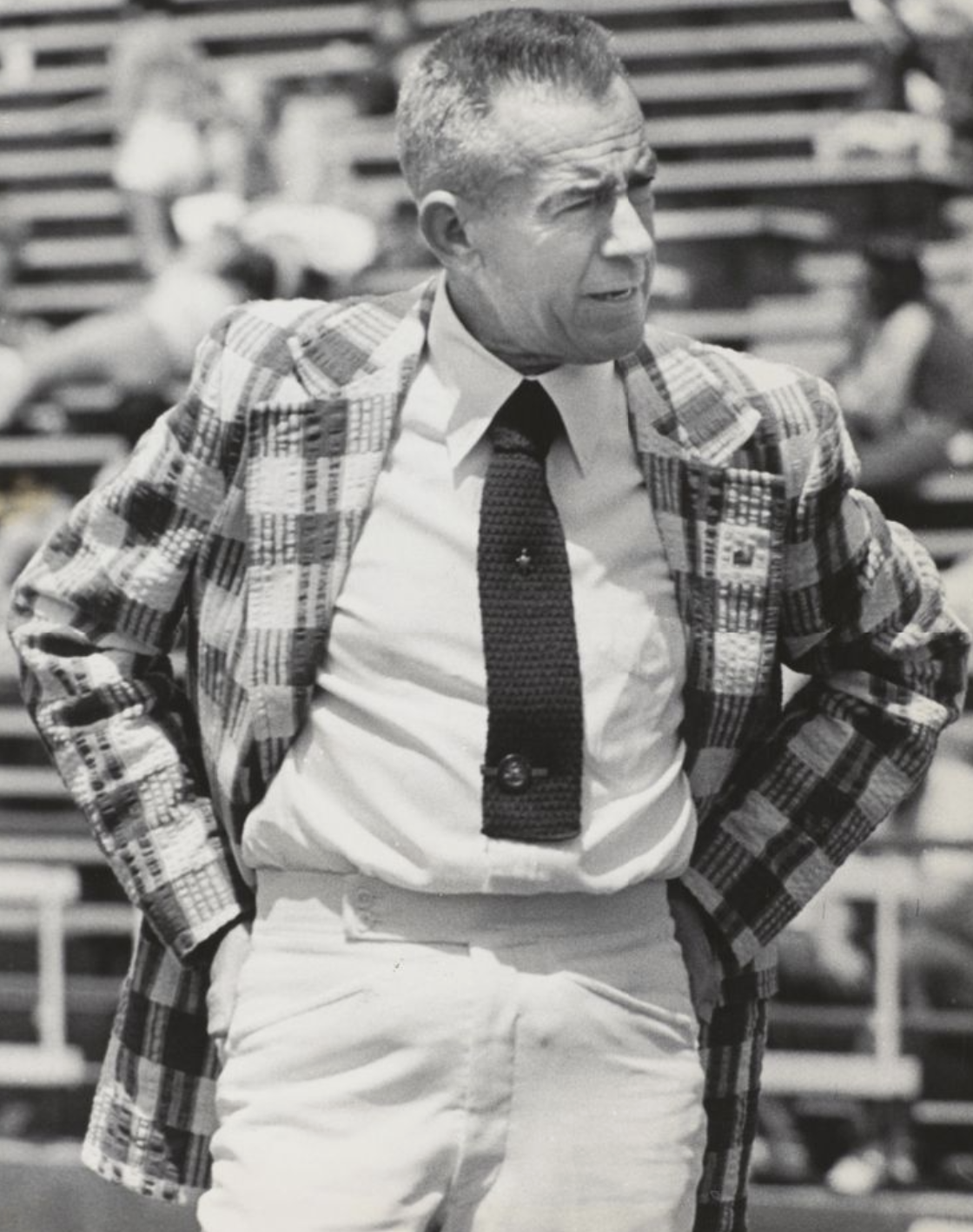

Back at the University of Maryland, the athletic department dragged its feet in the years directly following Title IX’s 1972 passage. James Kehoe (the University’s athletic director), Dorothy McKnight (the women’s athletic coordinator), as well as many other members of the athletic department opposed Title IX.24 UMD’s women’s athletics budget in 1972 was $23,624 (Kehoe had claimed a larger budget, reportedly closer to $73,000). Men received about $2.4 million. Of course, this pointed toward massive budgetary disparities in facilities, equipment, travel, and more – including scholarships.25

Historically, the University had granted athletic scholarships only to men. But to maintain equality among men’s and women’s teams, Title IX required that the University give scholarships to women as well. Many – including some administrators for women’s athletics – feared this would lead to the same cutthroat recruitment practices, which characterized men’s sports.26 McKnight said, “I have too much pride to sit on some 18-year-old girl’s doorstep and beg her to come to the University.”27 She even went so far as to say that she would quit if forced to recruit under the Title IX regulations.28

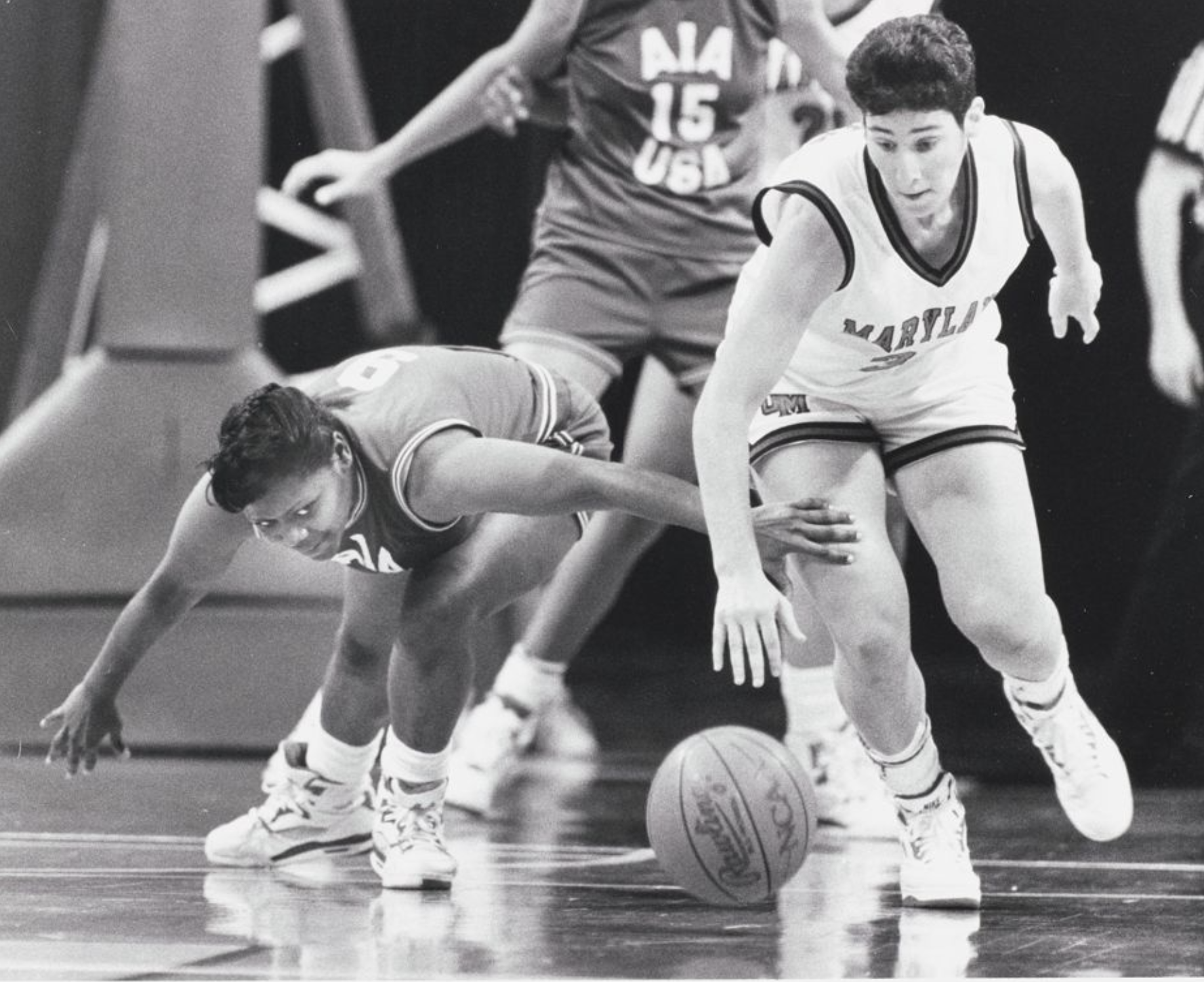

In 1973, Carl Croyder filed a complaint against the University for these exact reasons. Carl was the father of Page Croyder, an athlete on UMDs’ basketball, volleyball, and track teams. He described the innate differences between the men’s and women’s athletic opportunities, and charged the University, and Kehoe, with non-compliance with Title IX.29 His complaints brought HEW to the University's door. HEW investigated discrimination on campus, paying extra attention to the athletic department. Croyder's lawsuit was perhaps the largest against the University at the time, but representative of a pattern of complaints laid against the athletic department regarding non-compliance.30

By 1978, the federal government required campuses to fully comply with Title IX. Since then, women’s participation in higher education and sports has changed dramatically. According to the NCAA, the 2023-24 school year saw an all-time high of women athletes.31 In 2022-23, the University of Maryland’s women’s lacrosse, field hockey, basketball, softball, and gymnastics teams were all ranked within the top 25 teams in the country.32

Over 50 years have passed since Bernice Sandler brought her suit against the University of Maryland and Title IX has succeeded in changing the landscape of college campuses across the U.S. At the same time, challenges and debates around the law continue. Sexual assault continues to affect 1 in 4 undergraduate women, and the conversation around Title IX today includes important questions about the inclusion of transgender women on campus and in athletics.

In addition, changing NCAA rules – which now allow college athletes to earn money by using their name, image, and likeness in promotional deals – have dramatically altered the landscape of college athletics..33 The question of whether Title IX should apply to NIL payments has turned into a political volleyball of sorts.

Footnotes

- 1

- 2

Karen Shih, “The Godmother of Title IX,” Maryland Today. June 22, 2022.; Katherine Q. Seelye, “Bernice Sandler, ‘Godmother of Title IX,’ Dies at 90,” The New York Times. January 8, 2019.

- 3

Bernice R. Sandler, “’Too Strong For a Woman’ – The Five Words that Created Title IX,” About Women on Campus, National Association for Women in Education, Spring 1997.

- 4

John Matthews, “HEW Pushed on College Sex Bias,” The Evening Star, January 25, 1971. 2.

- 5

John Matthews, “HEW Pushed on College Sex Bias,” The Evening Star, January 25, 1971. 2.

- 6

Bernice R. Sandler, “’Too Strong For a Woman’ – The Five Words that Created Title IX,” About Women on Campus, National Association for Women in Education, Spring 1997.

- 7

John Matthews, “HEW Pushed on College Sex Bias,” The Evening Star, January 25, 1971. 2.

- 8

John Matthews, “HEW Pushed on College Sex Bias,” The Evening Star, January 25, 1971. 2.

- 9

Karen Shih, “The Terp Behind Title IX,” One Maryland, Spring 2022 Issue.

- 10

Bernice R. Sandler, “’Too Strong For a Woman’ – The Five Words that Created Title IX,” About Women on Campus, National Association for Women in Education, Spring 1997.

- 11

Stephen Neary, “’Sexism’ Charged to Md. U,” The Sunday Star, February 22, 1970. 51.

- 12

Stephen Neary, “’Sexism’ Charged to Md. U,” The Sunday Star, February 22, 1970. 51.; Bernice R. Sandler, “’Too Strong For a Woman’ – The Five Words that Created Title IX,” About Women on Campus, National Association for Women in Education, Spring 1997.

- 13

Sandy Fleishman, “Panel informed sexists ‘hard to change,’” The Diamondback (College Park, MD), March 19, 1971. 8.

- 14

Karen Shih, “The Terp Behind Title IX,” One Maryland, Spring 2022 Issue.

- 15

John Matthews, “HEW Pushed on College Sex Bias,” The Evening Star, January 25, 1971. 2.; Alan Lewis, “Female treatment investigated,” The Diamondback (College Park, MD), April 15, 1970. 2.

- 16

John Matthews, “HEW Pushed on College Sex Bias,” The Evening Star, January 25, 1971. 2.

- 17

John Matthews, “HEW Pushed on College Sex Bias,” The Evening Star, January 25, 1971. 2.

- 18

“Hidden Voices: Bernice Sandler, “Godmother” of Title IX,” NYC Public Schools.

- 19

John Matthews, “HEW Pushed on College Sex Bias,” The Evening Star, January 25, 1971. 2.

- 20

- 21

Bernice R. Sandler, “’Too Strong For a Woman’ – The Five Words that Created Title IX,” About Women on Campus, National Association for Women in Education, Spring 1997.

- 22

“History of Title IX,” Women’s Sports Foundation, August 13, 2019.

- 23

Katherine Q. Seelye, “Bernice Sandler, ‘Godmother of Title IX,’ Dies at 90,” The New York Times. January 8, 2019.

- 24

Dave Landau and Larry Weisman, “Sports department plots path towards financial security,” The Diamondback (College Park, MD), October 22, 1974. 5.; Selena St. Andre, “50 Years Since Title IX at the University of Maryland,” Terrapin Tales from the University of Maryland Archives. June 22, 2022.

- 25

Selena St. Andre, “50 Years Since Title IX at the University of Maryland,” Terrapin Tales from the University of Maryland Archives. June 22, 2022.; Kristy Larson, “Athletic Department to be Probed,” The Diamondback (College Park, MD), February 27, 1975. 1.

- 26

- 27

Kristy Larson, “Athletic Department to be Probed,” The Diamondback (College Park, MD), February 27, 1975. 1.

- 28

Kristy Larson, “Athletic Department to be Probed,” The Diamondback (College Park, MD), February 27, 1975. 1.

- 29

Kristy Larson, “Athletic Department to be Probed,” The Diamondback (College Park, MD), February 27, 1975. 1.

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)