D.C.'s Own "Brown vs Board"

Ask most people what Supreme Court case ended public school segregation and (perhaps after checking their smartphone) they will say, “Brown vs. Board of Education.” That is would be correct… for most of the country. But, for citizens in the federally-controlled District of Columbia another case was more important.

In 1950, the District of Columbia opened John Philip Sousa Junior High School in Southeast, D.C. Eleven parents of African American students, including Spottswood Bolling, petitioned the city to operate Sousa as an integrated school. However, the request was denied despite the fact that the new school had empty classroom space available.

James Nabrit, Jr., a law professor at Howard University, filed the suit against the District’s school superintendent Melvin Sharpe on behalf of the families. The D.C. case, Bolling vs. Sharpe, reached the Supreme Court on December 10, 1952 along with several other school desegregation cases. These other cases, which originated in the states, were consolidated into Brown vs. Board of Education.

The court published its decisions for both Bolling and Brown on May 17, 1954. In Brown, it ruled that the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment prevented states from segregating schools on the basis of race. But, because D.C. was a federally controlled area and not a state, the justices needed another way to strike down segregation in the Bolling case.

The solution that they came up with was the doctrine of “reverse incorporation.” In a nutshell, this doctrine interprets the Due Process Clause of the 5th Amendment (which states that no American could “be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law”) such that it applies the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment to the federal government, even though the 14th Amendment specifically only addresses the States.[1] The logic might seem a little roundabout but the basic idea is that the federal government is bound to – or “incorporated” into – the Equal Protection Clause.[2]

Confused yet? It’s okay. This is complicated stuff. If it makes you feel any better, many constitutional scholars have debated the court’s interpretation of the Constitution in the Bolling case for decades.

The bottom line is that the Court was looking for a way to bring about desegregation across the country. However, as we've seen before, the District's unique legal status made things a little more difficult than in the state-based school integration cases consolidated under Brown. But the court pulled it off. Specifically, the justices determined that the District’s segregated schools denied African American children due process of the law because there was no legitimate government purpose to make school assignments on the basis of race.[3]

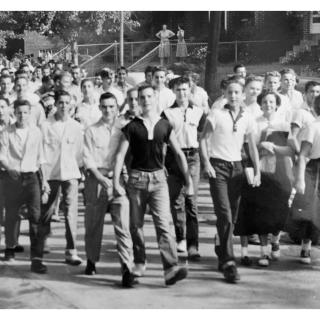

After the ruling, D.C. schools began the process of integration quickly. On September 13, 1954, schools in the city opened with integrated faculties and student bodies.

Footnotes

- ^ Primus, Richard, “Bolling Alone,” Columbia Law Review, May 2004. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=464847

- ^ Williams, Ryan C., “Originalism and the Other Desegregation Decision,” Virginia Law Review (Forthcoming) Posted on Social Science Research Network. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2166569

- ^ “Bolling v. Sharpe (District of Columbia),” The Leadership Conference. http://www.civilrights.org/education/brown/bolling.html

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)