After Bolling: School Desegregation in DC

“No one knows how much trouble we went through out here in southeast Washington trying to get suitable facilities for our children,” Luberta Jennings told the Washington Afro-American on May 18, 1954, the day after the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed segregation in public schools.[1]

Indeed, the Jennings family had been on the front lines of the fight for equality in Washington for the better part of four years. In the summer of 1950, Luberta and her husband, James, members of Campbell AME Church in Anacostia, had joined the Consolidated Parent Group’s grassroots effort to desegregate District schools.

The Jennings had signed up two of their children, Adrienne and Barbara, to be among the group of students who would attempt to enroll at the all-white John Philip Sousa High School in September 1950. The students were turned away because of the color of their skin, and Adrienne and Barbara were soon listed as two of the plaintiffs of the Bolling v. Sharpe case that would go on to be heard by the Supreme Court.

Most chronologies of this story often leave off at the Supreme Court decision, a nice bow-on-top finish to a long struggle against segregation, but in reality, the process of integrating the schools was far from over.

“A Great Day for DC”

On the fateful day of the Supreme Court decision, Adrienne Jennings was in class at Spingarn High School when the news broke, and when she returned home her mother told her “this was a great day for DC.”[2]

Spottswood Bolling, whose name would be burnished into history by the landmark case, avoided the press for years while the case was being litigated.[3] On the day of the verdict, Bolling was pulled out of class unexpectedly and told to go home early. He feared something had happened to his mother. “When a teacher explained that he had, in name at least, won one of the most important Supreme Court cases in history and that nothing was wrong at home, Spottswood was relieved and disinterested.”[4]

While Adrienne Jennings rushed home to celebrate with her mother, Bolling stopped by the neighborhood park to play a game of softball with friends. After winning his softball game, Bolling returned home to talk to the press about the Supreme Court verdict, the apparently less pressing of the two victories that day in the young Bolling’s mind. Finally after some “prodding” from his mother, Bolling gave a meager response to the press, “It will help the future of the race. Help other children. Better teaching, better space, better books.”[5]

Although the young students likely came to realize the importance and significance of their actions, they were in the moment--the temporal place where kids typically reside--more concerned about the impacts on their young social lives and adolescent educations. For many of the children, the news of court-mandated integration caused mixed feelings about the future of their education. Integration meant that students may have to transfer schools, possibly leaving their friends and classmates. Ultimately, both Spottswood Bolling and the Jennings sisters finished their schooling at Spingarn High School.

“To Be Accomplished with the Least Possible Delay”

Upon losing their case in the Supreme Court, District school administrators were also left to figure out how best to move forward. These officials were now tasked with combining two separate school systems, with two sets of teachers, two sports programs, and two student bodies, into one cohesive system. Between the over 100,000 students in DC Public Schools, there were merely six employees that spanned the two systems.[6]

Superintendent Hobart Corning initially dragged his feet on supporting the verdict, signalling that he intended to wait until the Supreme Court gave direct orders on “how and when” to integrate. On the day of the verdict, his office released the following statement:

It would be futile and totally impossible for the Superintendent of Schools to make any statement concerning the deliberations of the Supreme Court until the exact nature of the Court’s decree is known. Questions...having to do with how and when then schools are to be integrated, are yet to be resolved by the Court.[7]

Due to pressure from the community and the federal government, this position became untenable, and Corning soon released an outline of his integration plan. The plan included several main principles, including that “complete desegregation of all schools is to be accomplished with the least possible delay.”[8] This position was a direct about-face from Corning’s previous stance and actions against desegregation. It also ran counter to the actions of many other Southern school officials, who delayed integration by taking advantage of the high court’s directive that integration happen “with all deliberate speed.”

Corning’s plan prioritized relieving overcrowded situations at Black schools, meaning Black students would transfer to under-capacity white schools while relatively few white students would be transferred to formerly Black schools. Critics of the proposal said this fell short of true integration.[8]

Additionally, although Corning said his desegregation plan would be in full effect by September 1955, many supporters of integration believed it to be unnecessarily slow in achieving full integration. There was a clause that would allow students to opt out of the new school maps and stay in their previous school until graduation. Some believed this would have the effect of delaying integration by several years.[9]

Dr. Margaret Just Butcher, a Howard English professor, experienced educator, and one of three Black members of the Board of Education at the time of the court decision, had been an ardent supporter of integration since before the verdict. She was the only dissenting vote to Corning’s initial plan, and she held Corning’s feet to the fire throughout the summer of 1954 to submit a full integration plan by the fall. Butcher even pressured him to cancel his summer vacation travel plans to stay in the District and finish drawing the new school boundaries. Due to Butcher’s diligence, the new school boundary map was released just six weeks after the verdict, and she continued to debate with Corning over the details.[9]

“We Were Rushed into this Thing”

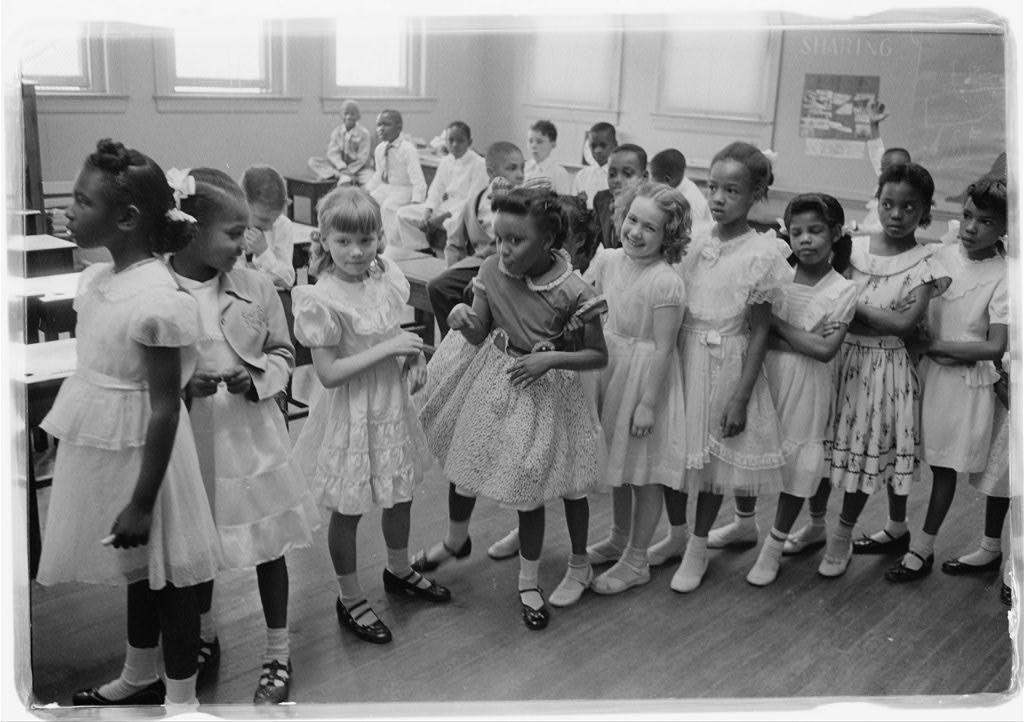

On the first day of classes in September 1954, about 3,000 Black students attended newly integrated classes at various formerly all-white schools across the District. “Comparatively few” white students transferred to formerly all-Black schools, however. The transfers were focused primarily in elementaries and junior high schools. McKinley High School was the only high school in the initial phase, with over 400 Black students attending newly integrated classes.

The Evening Star, echoed by other papers, heralded the integration efforts as successful under a frontpage headline stating, “School Opening Runs Smoothly, Race Bars End.”[10]

This initial success prompted Corning to speed up the timeline of his integration plan. After the first week of school, the Superintendent announced that the rollout would be finished by February 1955, instead of September, and the integration of the rest of the city’s high schools would go into effect immediately.[11]

However, this initial success wouldn’t last.

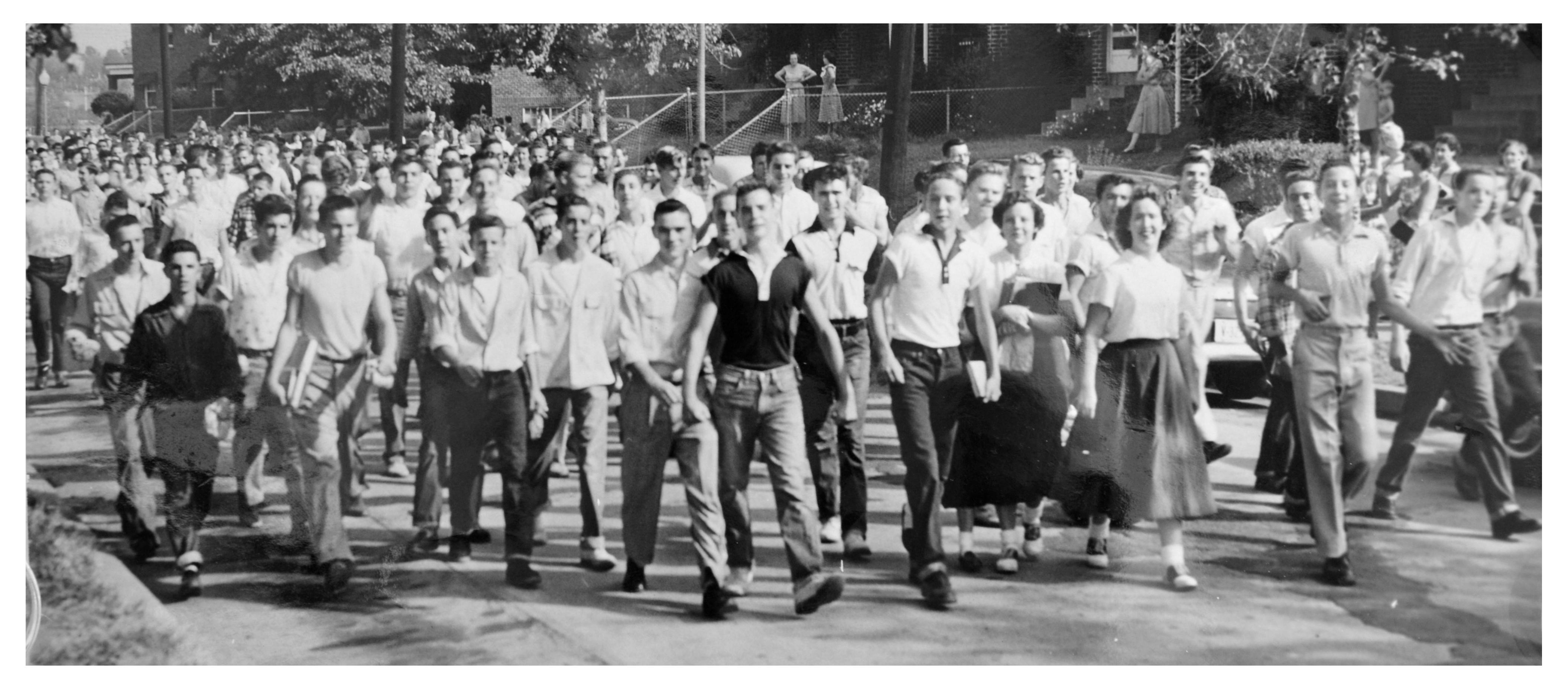

Two weeks later, on Monday, October 4, 300 white students at Anacostia High School and another 140 at McKinley High School--two formerly all white schools--skipped classes and went on strike to protest the newly integrated classrooms.[12]

The Washington Afro-American captured the scene, which was an almost mocking parallel to the boycott against segregation in the early days of the struggle. “At Anacostia, demonstrators walked up and down R St holding up crude cardboard signs with race-baiting remarks,” the paper reported. A caption under a photograph of the striking students pointed out the obvious:

And They Can’t Spell--Crude signs improvised on scrap cardboard are carried by this group of Anacostia High School pupils, Washington, who Monday protested transfer of 30 colored pupils to the previously all-white school. One of the signs reads, “Let Us Pick Our Own Freinds” with the word ‘friends’ misspelled. Another reads, “Send ‘em Back to Africa” and the third, “We Won’t Go Back.”[12]

The immaturity and learned racism of the students was evident when reporters asked them about their motives for striking. One Anacostia student explained, “It might work out if [integration] had started in kindergarten. The trouble is that half of us have been brought up to hate them, and half of us have been brought up to get along with them.”[12]

A student at McKinley had difficulty articulating why he even felt that way. “I am fighting desegregation,” he said, “I don’t know why, but colored are made to stay by themselves and we by ourselves.”[12]

The acting principal of Anacostia High School, Eugene Griffith, walked out of the school to appeal to the crowd of striking students. “I came out as your friend, and I am simple enough to believe you are my friends…Please believe me I am asking you to report to classes,” he pleaded to the students. The crowd of students booed him, and he returned inside without a single student following his lead. “Well, I gave it a try anyway,” Griffith remarked to the Evening Star.[13]

After shouting down Griffith, the striking Anacostia students marched to the nearby Kramer Junior High School to enlist the younger students in their protest. They shouted “Come out, Come out” at the school, but none of the students joined. Later, while the junior high students were outside at recess, several dozen deserted their classmates, scaled the wire fence of the school yard, and joined the strikers.[14]

At Eastern High School, principal John Collins was more successful than Griffith in initially quashing the strike. He gathered students at an assembly and urged them to not be “led around by your nose by troublemakers.” He also reportedly threatened expulsion of any rebellious students, telling a reporter, “If they come and loiter and refuse to attend class, they are in defiance of my authority. I have the right to expel them and I will.”[14]

On Tuesday, the protests spread from Anacostia and McKinley to several other schools across the District, including Eastern High School where between 200 and 300 students defied their principal’s threat of expulsion. Aside from the three high schools, students also protested at six junior high schools: Kramer, Taft, Hine, Macfarland, Stuart, and Sousa Junior Highs. Most of these junior high students were less obstinate than the high schoolers, and many were persuaded to return to class soon after the school day began.[15]

On Wednesday, Bryant Bowles, an infamous white supremacist who founded the “National Association for the Advancement of White People” to combat school integration, visited Anacostia High School after the strike to show support for the students. He told the students, “You have my backing all the way as long as there’s no violence and you stay off the streets.”[16]

School officials at both McKinley and Anacostia High Schools held meetings with the striking students to urge them back to school. At one such meeting at Anacostia, one student presented a “petition of grievances,” with such juvenile and outright racist reasons as “We were rushed into this thing too fast,” and “We don’t want to shower with them,” referring to Black students. The list of twelve grievances also noted that the dissident students “do not believe this mob rule is the best way to stop integration but if other actions fail this must be resorted to.”[16]

Contrary to the signs held by students at Anacostia on the first day of the strike, the students did go back to class over the course of the week, due to a concerted effort by District officials, police, and school administrators to push back on the protests. Police increased officer presence near the schools on the second day of the strike, and officers were instructed to “revoke the driving permits of any juveniles who use their cars to participate in an anti-integration demonstration.”[14]

Superintendent Corning issued an ultimatum to the students: return to class by Friday or be barred from participating in any extracurricular activities, including sports teams, drama performances, and the cadet corps. This threat worked, and by Thursday, the protests had mostly subsided.[17]

The protests in October 1954 were the last organized action against school integration, but the integration of schools coincided with and accelerated the rise of white flight from the urban areas of the District to the bedroom communities of Maryland and Virginia, leading to a form of de facto segregation in District schools.[18] The number of white public school students dropped by 30% in the two years after the Bolling verdict, and by 1965, white students made up just about 10% of all public school students, down from around 50% before Bolling.[19]

Footnotes

- ^ “DC Parent was sure of Decision” Washington Afro-American. May 18, 1954. https://news.google.com/newspapers/p/afro?nid=BeIT3YV5QzEC&dat=19540504…

- ^ “Recovering Untold Stories: An Enduring Legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision." 2018. University of Kansas Library. http://www.npshistory.com/publications/brvb/recovering-untold-stories.p…

- ^ Devlin, Rachel. A Girl Stands at the Door: The Generation of Young Women Who Desegregated America’s Schools [New York: Basic Books, 2018] p. 172-173

- ^ Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 18 May 1954. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1954-05-18/ed-1/seq-…;

- ^ Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 18 May 1954. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1954-05-18/ed-1/seq-…;

- ^ Stewart, Alison. First Class: The Legacy of Dunbar, America’s First Black Public High School [Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2013] p. 170-171

- ^ Rogers, Jeanne. “No Quick Integration Seen in D.C. Schools” Washington Post, May 18, 1954. https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/docview/148491612/pa…

- a, b Borchardt, Gregory. "Making D.C. Democracy’s Capital: Local Activism, the ‘Federal State’, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Washington, D.C." The George Washington University, August 31, 2013.

- a, b Stewart, Alison. First Class: The Legacy of Dunbar, America’s First Black Public High School [Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2013] p. 171-172

- ^ Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 13 Sept. 1954. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1954-09-13/ed-1/seq-…;

- ^ “‘Corning Plan’ Speeded Up, Mixed Schools by February” Washington Afro-American, September 21, 1954. https://news.google.com/newspapers/p/afro?nid=BeIT3YV5QzEC&dat=19540921…

- a, b, c, d “‘Will Not Give In’ Says Supt. Hobart Corning, May Invoke Compulsory School Law” Washington Afro-American, October 5, 1954. https://news.google.com/newspapers/p/afro?nid=BeIT3YV5QzEC&dat=19541005…

- ^ Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 04 Oct. 1954. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1954-10-04/ed-1/seq-…;

- a, b, c “Some Pupils Demonstrate To Protest Integration: Murray Cancels All Police Leaves; Corning Points Out Duties of Parents Integration Protested by Some Pupils” The Washington Post and Times Herald (1954-1959). Oct 5, 1954. https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspaper…

- ^ Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 05 Oct. 1954. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1954-10-05/ed-1/seq-…;

- a, b Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 06 Oct. 1954. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1954-10-06/ed-1/seq-…;

- ^ Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 07 Oct. 1954. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1954-10-07/ed-1/seq-…;

- ^ Williams, Juan. "Puzzling Legacy of 1954" Washington Post, May 17, 1979. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1979/05/17/puzzling-leg…

- ^ Asch, Chris Myers, and George Derek Musgrove. Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation's Capital [Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2017] p. 314

![Parents and students protest in the streets of Anacostia. [Reprinted with permission of the DC Public Library, Star Collection © Washington Post] Parents and students protest integrated schools in Anacostia. Some hold signs, including one that reads, "Let us pick our KKK friends." A woman pushes a baby in a stroller. A sign on the stroller reads, "Do we have to go to school with THEM?"](/sites/default/files/styles/embed_full_width/public/Anacostia%20Strike.jpg?itok=yEGSmodp)

![This integrated classroom at Anacostia High School is the culmination of a seven year struggle against DC's segregated school system. [Source: LOC] Integrated classroom at Anacostia High School](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/AHS%20Class_0.jpg?itok=GNxSJFox)

>

>