Cold-Blooded Murder in Lafayette Square: The Sickles Tragedy of 1859

On the morning of February 27, 1859, Philip Barton Key was shot multiple times by the deranged Daniel E. Sickles in the middle of Lafayette Square. Sickles’ motive? ... The discovery of an intimate affair between his wife and good friend.

Now Washington, D.C., has had its fair share of scandals, political pandemonium, and secret trysts over the years. But the Sickles tragedy provided a particularly scandalous dance between sex and politics even by Washington standards. After all, it’s not every day that a Congressman commits cold-blooded murder in broad daylight on a city street.

Let’s meet the three players.

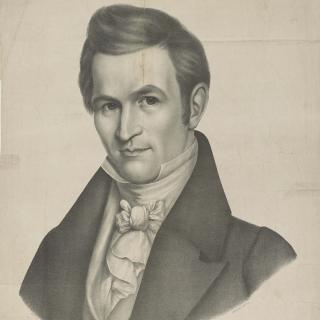

Daniel E. Sickles was an affluent New York congressman, lawyer, and confidant of President Buchanan. Later in life, he was an honored war veteran, diplomat and Medal of Honor winner. Seems like he was quite the guy… But Sickles also had a dark side to him, particularly when it came to women. He once seduced a married woman and blackmailed her husband. And, at age 32, Sickles used his sly moves to seduce a 16-year-old that he impregnated and married.[1]

Teresa (Bagiolia) Sickles was the “lucky” lady. The daughter of a distinguished New York Composer, young Italian Bagiolia was described as “soft, lovely, and youthful” at the time of her marriage to Sickles.[2] Unfortunately for fair Teresa, Sickles was known to have a number of mistresses, with whom he spent far more time than his own wife. In her solitude, she sought out the company of a dashing local lawyer.

Philip Barton Key was Teresa’s “other man.” As the D.C. District Attorney and son of Francis Scott Key, author of the Star-Spangled Banner, he was well-liked and respected in society. A handsome widower, Phillip was also quite illustrious amongst the ladies.

Daniel and Teresa Sickles had been close friends with Phillip Barton Key for some time before the trouble started. When Sickles was away on “business,” Key often accompanied Teresa to events around town. However, over time, their relationship developed into something a little more than a friendship. Eventually, the two began to meet privately in a home that Key rented down the street. Teresa and Philip’s love affair became widely known to the public while Sickles remained oblivious.[3]

On Friday, February 25, 1859, Daniel Sickles received an anonymous letter informing him of his wife’s relations with Key. Gripped with rage, Sickles confronted his wife about the letter and forced her to sign a degrading statement confessing her affair.[4]

Sunday came and Key made his usual secret call to Teresa by waving his handkerchief outside her window. Regrettably, for Key, Sickles was watching this time, not Teresa. Storming out of the house in a fit of rage, Sickles shouted “Key, you scoundrel, you have dishonored my home; you must die!”[5]

Sickles shot Key not once, but twice. Despite a struggle from Key and his shouts to the bystanders, Sickles's second shot went straight through Key’s chest, leaving him gasping for breath in the middle of Lafayette Square. Key was carried into the nearby clubhouse as Sickles calmly placed his gun in his coat pocket and walked away. With advice from his friend Samuel Butterworth, Sickles agreed to turn himself in.

The trial swept across the headlines. Was it murder or adultery? Although everyone involved broke the law, who would take the fall?

Immediately, Sickles gathered a strong team of lawyers to defend his case. Edwin M. Stanton, the future Secretary of War under President Lincoln was joined by top criminal defense lawyer James T. Brady, plus six other members of the Bar Association of DC, at no cost to Sickles. Their opponent was an assistant to Key, young and unversed.

For the first time in legal history, a temporary insanity plea was used, arguing that Sickles was simply too overcome with passion to control himself. And despite Daniel Sickles's own infidelity, the case quickly flipped from a murder trial to an adultery trial, publically scorning Teresa and making a kind of hero out of Sickles. After a 20-day trial, Sickles was found not guilty.[6]

For more details of the incident, including a detailed account of the trial, check out Nat Brandt’s book The Congressman Who Got Away with Murder. A special thanks to The Historical Society of Washington, D.C. for their help on this post and for providing the cover photograph.

Footnotes

- ^ Baker, Kevin. "The Man Who Got Away With Everything." The New York Times, sec. H11, April 14, 2002.

- ^ De Witt, Robert M. De Witt's Special Report: Trial of Hon. Daniel E. Sickles for shooting Philip Barton Key, Esq. New York: Robert M. De Witt Publishers, February 27, 1859. Courtesy of The Historical Society of Washington, D.C. Accessed June 17, 2013, 5.

- ^ Rezneck, Daniel A. "It Didn't Start With O.J. Like the Simpson Saga, the 1859 Murder Trial of Dan Sickles Gripped the Nation." The Washington Post, sec. C5, July 24, 1994.

- ^ Rezneck, Daniel A.

- ^ De Witt, Robert M. De Witt's Special Report: Trial of Hon. Daniel E. Sickles for shooting Philip Barton Key, Esq. New York: Robert M. De Witt Publishers, February 27, 1859. Courtesy of The Historical Society of Washington, D.C. Accessed June 17, 2013, 4.

- ^ Rezneck, Daniel A.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)