The Last Fatal Duel in Congress: Jonathan Cilley vs. William Graves

Over the course of American history, disagreements in Congress have become more than accepted in daily life. Partisanship continues to increase as time goes by, much to the chagrin of many in the House chambers. Despite this increasing hostility, Americans can be reasonably assured that their elected representatives won't resort to the age-old practice of dueling... But that wasn't the case in 1838.

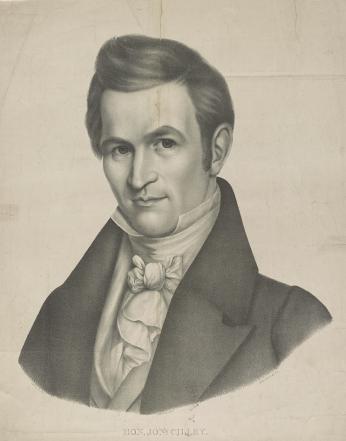

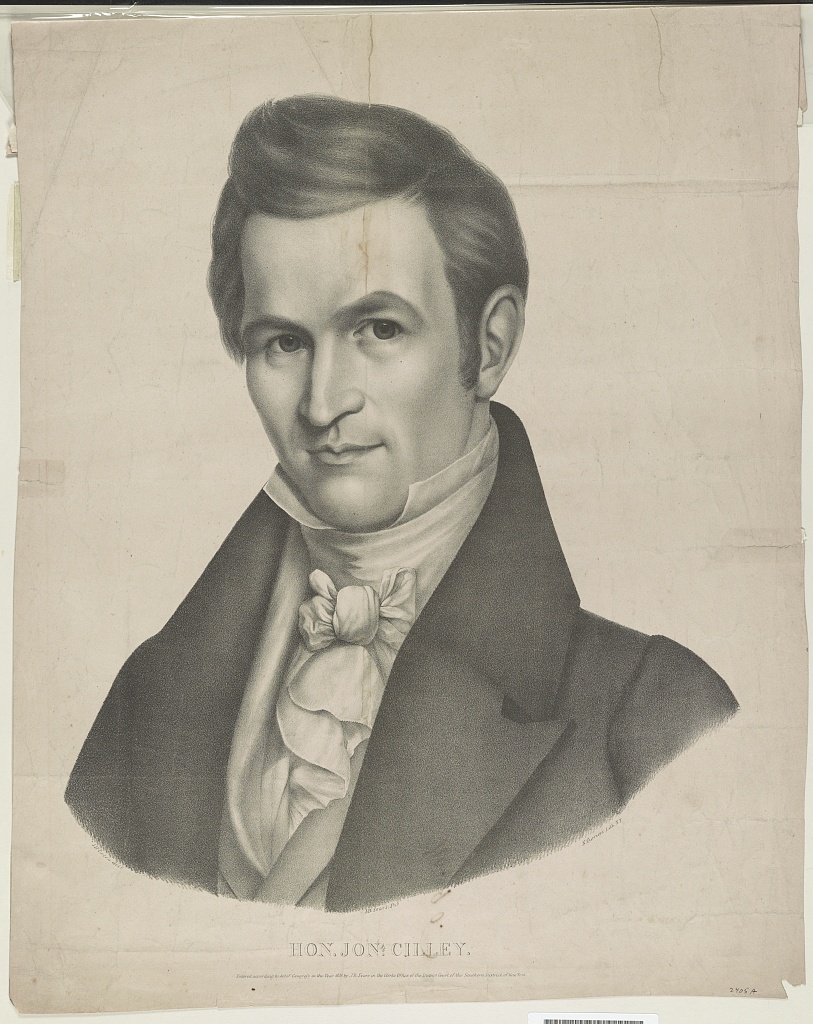

Jonathan Cilley was born in Nottingham, New Hampshire, in 1802. He attended Bowdoin College, becoming close friends with the likes of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and future President Franklin Pierce. Cilley would become a prominent member of the Democratic party almost immediately after graduating, settling down in Thomaston, Maine. He soon became an attorney under Sen. John Ruggles (D-ME). While in Thomaston, he met his wife, Deborah.1 Cilley was elected to Maine’s House of Representatives in 1832 and remained there for five years.2

Cilley’s first taste of political life was sour. He indicated in letters to Deborah that other Democratic politicians seemed to be conspiring against him. Cilley, however, was a fighting politician with an ambition to climb the political ladder, though he was disturbed by the “jealousy & rivalry among our friends.”3 He wrote in 1833, “I know that by many here, I am hated and feared. I am hated because I am feared.”4 In 1837, Cilley was elected to the House of Representatives for Maine’s 3rd District. He entered his position with confidence and excitement, writing to Deborah, “I never felt stronger or more confident in my life.”5

Democrats, such as Cilley and the incoming president, Martin Van Buren, had a lot on their hands within the year. The Panic of 1837 hit the U.S. hard, resulting in financial complications that would last until the mid-1840s and leave a legacy as the worst financial crisis of the 19th century.6 The depression was caused, in large part, by Van Buren’s predecessor, Andrew Jackson, and his refusal to renew the contract of the Second U.S. Bank during the “Bank War.” Democrats, the party of Jackson, blamed state bankers for lending money to anyone they saw fit while maintaining dangerously low reserve ratios. Whigs, the opposition party and in the minority in 1837, blamed Jackson and his old Vice-President, Van Buren.7

Democrats like Cilley fervently defended Jackson and Van Buren’s handling of the Bank situation, determining that the Bank was corrupt and this corruption needed to be addressed.8 Whigs and their supporters, such as James Watson Webb, a newspaper editor, levied their own accusations of Democratic corruption. Webb purchased two newspapers, the Courier in 1827 and the New York Enquirer in 1829, consolidating them into the New York Courier and Enquirer.9

With Cilley now in the national arena, he was quickly at odds with Henry A. Wise (W-VA). Wise, a gruff Virginian, first clashed with Cilley in January 1838, criticizing Van Buren’s handling of Seminole Indian removal from Florida. Cilley accused Wise of being fond of Native and African Americans, a charge which could hurt Wise politically.10 On February 12, 1838, Wise called for a committee to weed out corruption in the House after an edition of Webb’s Courier and Enquirer accused an unnamed Democratic congressman of corruption. Wise stated, “[t]he character of the authority upon which the charge is made, is vouched for as respectable and authentic by the editor of the Courier and Enquirer, in whose paper it appears, and the House is called upon to defend its honor and dignity against the charge.”11

Cilley would have none of it. He accused Wise of making “base charges,” and lambasted Webb’s coverage of the Democrats as hypocritical:

“[I] knew nothing of this editor; but if it was the same editor who had once made grave charges against [the Bank] of this country and afterwards was said to have received facilities to the amount of some $52,000 from [the Bank, and gave it his hearty support, [I do not] think his charges were entitled to much credit in American Congress.”12

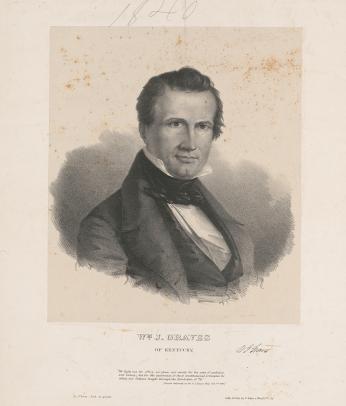

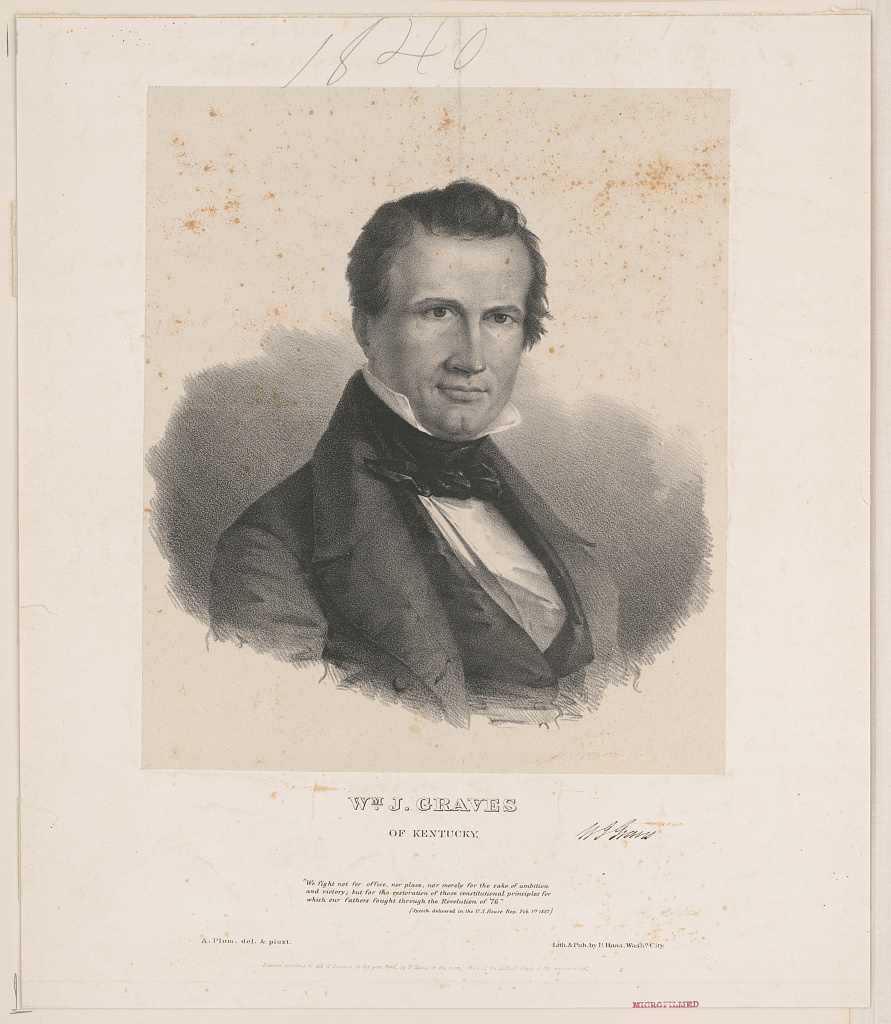

Webb, angered by Cilley’s counter-accusation of bribery from the Bank, announced – without a shred of evidence – that Cilley was the corrupt congressman.13 Webb insisted that another Whig politician and personal friend, Rep. William J. Graves (W-KY) hand a note to Cilley asking if he would admit to the corruption accusations laid before him. Cilley refused to take the note and apologized, noting his respect for Graves. He refused to be goaded into a fight.14

The news of this interaction spread quickly. Whig newspapers mocked Cilley’s masculinity. Indeed, many Whig-leaning publications perceived northern politicians as pious and timid, whereas their southern counterparts were fearless brawlers who wouldn’t back down from a challenge.15 A correspondent for The Sun ridiculed Cilley:

“I fancy Mr. Cilley will not think of ‘standing a gun-powder and lead epistle.’ In the section of the country from which he came, duelling is considered an irresponsible and irreligious pursuit, and the man who flogs his neighbor with anything larger or more violent with an ox-gourd, is set down for a rap rascal…As Mr. Cilley is a man of great practical and devotional piety, he may possibly eschew the pistol and seize the ox-gourd.”16

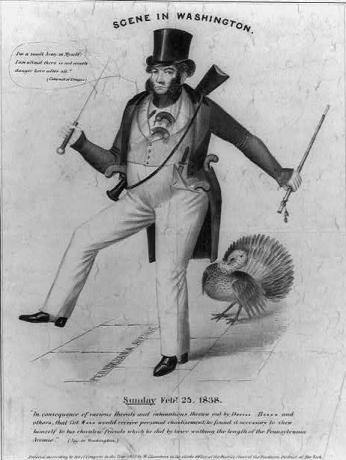

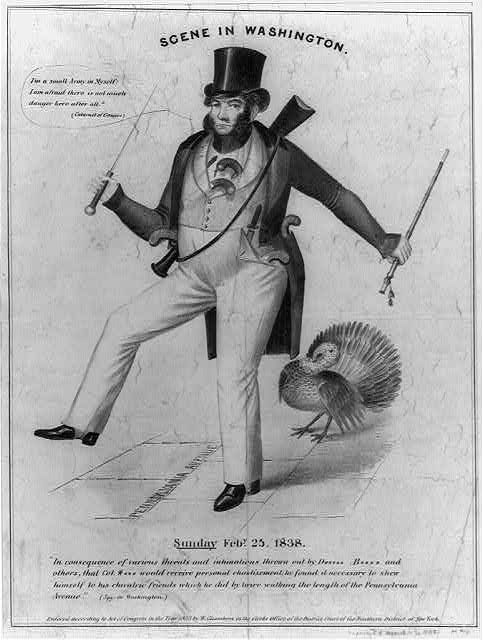

Graves, offended by Cilley’s refusal to acknowledge Webb, sent a formal challenge of a duel to Cilley on the morning of February 23, 1838.17 Cilley accepted the challenge, and it was decided that the two men would duel at noon the next day.18 Allegedly, Webb wanted to face Cilley in a duel, though he never formally challenged Cilley. Despite not challenging him, Webb bragged that he planned to shoot Cilley in the arm if he refused to duel. Webb's claim was ridiculed in northern newspapers.19

As word got around Congress of Cilley and Graves's exchange, John Quincy Adams, former president-turned-representative opined:

“There was an agitation in the [H]ouse different from that which is occasioned by an irritated debate; a restless uneasy whispering disposition, clustering into little groups with inquisitive looks, listening ears, and varying reports…At one time it was rumoured that the parties had been separated by interposition of a magistrate. At another…they had adjusted their differences on the field and returned to their quarters.”20

Despite the air of uneasiness, no one was able to stop Cilley or Graves.

On February 24, 1838, each duelist brought a group of congressmen to fulfill the various roles in the duel: the “seconds” of each duelist who would reload the duelists’ rifles, “friends” who would act as witnesses, and two doctors. George W. Jones (D-WI) acted as Cilley’s second while Wise acted as Graves’s second. State Rep. Jesse A. Bynum (D-NC) and Col. James W. Schaumburg joined as Cilley’s friends while Sen. John J. Crittenden (W-KY) and Rep. Richard Menefee (W-KY) joined as Graves’s friends. Rep. Alexander Duncan (D-OH) – who had no medical experience – acted as Cilley’s doctor while J.M. Foltz – who was a Navy surgeon – acted as Graves’s doctor. Reps. John Calhoon (W-KY) and Richard Hawes (W-KY) also followed behind with blankets in case Graves was injured.

Three carriages carrying ten congressmen and others set out for Maryland since dueling was illegal in Washington, D.C. A man named Grafton Powell, who later testified he had a lifelong dream of witnessing a duel, tagged along. As Powell told a member of the party, “Give my compliments to [Cilley and Graves] and tell them that I am determined to see the duel, if I had to take a shot for it.”21

Speaker of the House Henry Clay attempted to stop the duel but was unable to locate the party.22 Meanwhile, the group arrived at the Bladensburg Dueling Grounds, located near the present-day Colmar Manor Community Park in Prince George's County Maryland, at about 3 p.m. Cilley and Graves were separated with rifles at the ready. The official congressional report following the incident stated, “[t]he position of Mr. Graves was near a wood, partly sheltered by it, and that of Mr. Cilley was on higher ground, in an open field.” It also noted that Graves’s rifle “was nearly twice as large as that of Mr. Cilley’s.” When asked “[g]entlemen, are you ready,” neither man rescinded their challenge.23 After the count of four, the duel commenced:

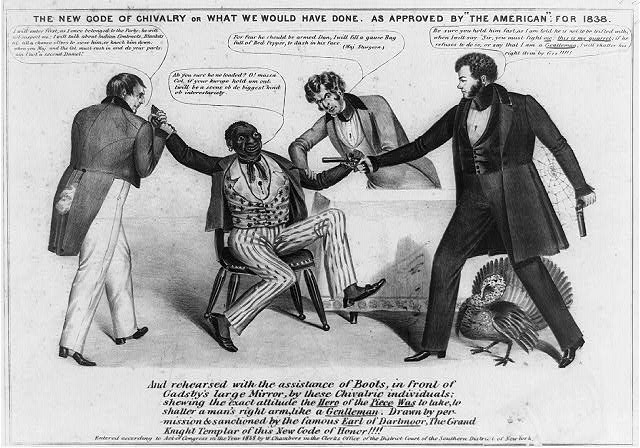

“Mr. Graves fired first, before he had fully elevated his piece; Mr. Cilley fired about two seconds afterwards. They both missed. [The witnesses] thought, from the motions and appearance of Mr. Graves, that he was hit. He at once said, ‘I must have another shot.’ Mr. Wise [said], ‘he positively, peremptorily, and repeatedly insisted upon another shot.’”24

Then, the second pair of shots fired, both missed again. The duelists agreed to move closer, making it much more likely that the next shot would find its mark.25

Between shots, James Brown, a farmer who owned the land where the Dueling Grounds were located, and his son ventured out to observe the duel. Brown asked Graves what they were doing, and Graves replied, “[we] were merely taking a little sport.”26 Brown continued to pepper Graves with questions: Are you fighting a duel? Are you members of Congress? Where are you from? Are you fighting over a debate? Graves shooed him away.27

Finally, the third set of shots rang out. Cilley was struck and fell to the ground, exclaiming “I am shot.” He died within 90 seconds.28 Jones ran over to his friend, muttering to himself, “My friend is dead.”29 Graves and Wise rushed over as well; Graves asked Jones “How is he?” Jones repeated, “My friend is dead, sir.”30

Cilley’s bloody corpse was wrapped in a blanket and loaded into his carriage to be carried back to his boarding house in Washington. Rumors of the duel had circulated around Washington so several onlookers were present to witness the carriage roll into the city. The carriage arrived at Cilley’s boardinghouse and his body was carried into his bedroom and placed on the floor. Further rumors spread that Cilley’s friends roamed the district with pistols in hand looking for Webb, the instigator. It would take a week for the news to reach the widowed Deborah Cilley in Thomaston.31

A furor broke out over Cilley’s death. Nathaniel Hawthorne, Cilley’s old college friend, wrote of the duel:

“A challenge was never given on a more shadowy pretext: a duel was never pressed to a fatal close in the face of such open kindness as was expressed by Mr. Cilley; and the conclusion is inevitable that Mr. Graves and his principal second, Mr. Wise, have gone further than their own dreadful code will warrant them, and overstepped the imaginary distinction which, on their own principle, separates manslaughter from murder.”32

Northern, Democratic, and Christian publications exploded with rage, blaming Graves entirely for Cilley’s wrongful death. The New England Farmer, and Horticultural Register asked:

“Is it possible that in a community where Law is said to reign, that men shalt cooly detail all the steps in such an atrocity and their own particular, direct, and urgent instrumentability in the affair, and thus defy the sovereignty of the law; and pass on in the midst of the Legislators and Magistrates of the land, without even the formality of the arrest? Good Heavens! What is the condition of [the] society in which we live!”33

A Massachusetts Christian magazine, Trumpet and Universalist Magazine, declared:

“We have, in a former number, expressed our opinion of the wicked, dishonorable, savage crime of dueling. It is a sin against God, who says, ‘thou shalt not kill.’ There is no justification for the practice…If either Mr. Graves or Wise had committed the offence in this State, which they have committed in Maryland, they would be taken and treated as murderers.”34

The Boston Recorder, with a headline that read “I Had Rather Be in the Place of Cilley, Than of Graves,” mused that Graves was “not yet beyond the reach of mercy. Penitence may find a place in his heart. The prayer may yet be offered from the depths of his tortured soul.”35 Whig newspapers conversely accused Democrats of using Cilley’s death for “electioneering purposes,” claiming that Cilley’s friends were assassins who murdered Cilley to get to Webb.36

On February 28, 1838, Cilley’s funeral was held in the Capitol’s rotunda. President Van Buren gave a eulogy before his Cabinet and Congress:

“Of [Cilley’s] conduct here I need not speak, for all who hear me, and all who knew Mr. Cilley in the other end of the Capitol, will bear testimony to his ability, to his open, frank, and determined course, to the high order of his talents, and powers as a debater, and to the respect and deference he paid to the rights of others. As a man, Mr. Cilley was warm, ardent, generous, noble; as a friend, true, faithful, abiding… In his death, Maine has lost one of her brightest ornaments, and the nation is bereft of a devoted patriot, and an ardent, zealous supporter of its free institutions.”37

Every congressman agreed to wear a “crape,” or black scarf, around their left arm for thirty days in a mourning practice popularized during the Victorian Era.38 Cilley was interred at the Congressional Cemetery but was later moved to Elm Grove Cemetery in Thomaston. Angry protestors of Cilley’s untimely death shouted outside his boardinghouse; handbills called for effigies of Wise and Webb to be burned.39

Two weeks after Cilley’s death -- apparently seeking to avoid another case where members of Congress arranged a duel and then traveled across state lines to carry it out -- Sen. Samuel Prentiss (W-VT) presented a bill to "prohibit the giving or accepting within the District of Columbia of a challenge to fight a duel." Violators faced five years of prison time. The bill made actually killing an opponent in a duel tantamount to murder.40 It was passed nearly a year after Cilley’s death on February 20, 1839.

Graves ultimately left Congress but otherwise went unpunished. He returned to his home state of Kentucky and was elected to Kentucky’s House of Representatives in 1843, where he remained until his death in 1848.41

The tragic encounter between Jonathan Cilley and William Graves was the last fatal duel between two members of Congress. However, as scholar Joanne Freeman has detailed in her book The Field of Blood, violence among politicians did not stop. In the decades leading up to the Civil War, members of Congress repeately clashed, often over issues regarding slavery.

In 1854, Rep. John C. Breckenridge (D-KY) threatened Rep. Francis B. Cutting (D-NY) with a duel over the Kansas-Nebraska Act, despite knowing it was illegal.42In 1859, David Colbreth Broderick (D-CA) was killed in a duel with California State Supreme Court Chief Justice David S. Terry. 43 Webb himself was shot in the leg during a duel with Rep. Thomas Marshall (W-KY) in New York City. He was sentenced to two years in Sing Sing prison for dueling but pardoned by New York’s governor.44

Thankfully, dueling became less common in the years after the Civil War. As anti-dueling laws began to be enforced more regularly, the practice died out.

Author’s Note:

For more information about violence in Congress prior to the Civil War, check out Joanne B. Freeman’s The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War.

For more on the life and death of Jonathan Cilley, check out Roger Ginn’s New England Must Not Be Trampled On: The Tragic Death of Jonathan Cilley

Footnotes

- 1

The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography (New York : J.T. White, 1924), 190, http://archive.org/details/nationalcyclopa03unkngoog.

- 2

Roger Ginn, New England Must Not Be Trampled On: The Tragic Death of Jonathan Cilley (Down East Books, 2016), 63, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/gwu/detail.action?docID=4206549.

- 3

Ginn, New England Must Not Be Trampled On, 64-5.

- 4

Joanne B. Freeman, The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War, First edition (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018), 79.

- 5

Freeman, The Field of Blood, 80.

- 6

David Glasner and Thomas F. Cooley, Business Cycles and Depressions: An Encyclopedia (New York: Garland Pub., 1997), 514-16, http://archive.org/details/businesscyclesde00glas.

- 7

William H. White, America’s Fiscal Constitution: Its Triumph and Collapse (New York: PublicAffairs, 2014), 80, http://archive.org/details/americasfiscalco0000whit.

- 8

Hugh J. Hastings, Ancient American Politics (New York, N.Y., United States: Harper, 1886), 136, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/wu.89073016206?urlappend=%3Bseq=142.

- 9

Initially, Webb bought the publication to praise Jackson but his handling of the Bank War led Webb to abandon the Democrats for the Whigs; “An Old Journalist Dead,” The New York Times, June 8, 1884, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1884/06/08/103619601.pdf.

- 10

Freeman, The Field of Blood, 81-2.

- 11

United States Congress, “Report of the Committee on the Late Duel” (Washington, D.C., United States: United States Congress, 1838), https://www.loc.gov/item/10002243/.

- 12

United States Congress, “Report of the Committee on the Late Duel.”

- 13

Hastings, Ancient American Politics, 136.

- 14

United States Congress, “Report of the Committee on the Late Duel.”

- 15

Freeman, The Field of Blood, 87.

- 16

“From Our Correspondent,” The Sun, February 23, 1838.

- 17

Freeman, The Field of Blood, 91-3.

- 18

United States Congress, “Report of the Committee on the Late Duel.”

- 19

W. Chambers, The New Code of Chivalry or What We Would Have Done. As Approved by “The American:” For 1838, 1838, graphic, American Cartoon Print Filing Series (Library of Congress), January 1, 1838, PC/US - 1838.C444, no. 2 (B size) [P&P], Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print, https://www.loc.gov/resource/cph.3b37764/.

- 20

Ginn, New England Must Not Be Trampled On, 171.

- 21

United States Congress, “Death of Mr. Cilley -- Duel. April 21, 1838. Submitted to the House of Representatives. May 10, 1838. Ordered to Lie on the Table, and to Be Printed” (Washington, D.C., United States: U.S. Government Printing Office, May 10, 1838), https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/SERIALSET-00336_00_00-007-0825-0000.

- 22

“Fatal Duel at Washington,” The Jeffersonian (Albany, United States: American Periodicals Series II, March 3, 1838).

- 23

United States Congress, “Report of the Committee on the Late Duel.”

- 24

United States Congress, “Report of the Committee on the Late Duel.”

- 25

United States Congress, “Report of the Committee on the Late Duel.”

- 26

United States Congress, “Death of Mr. Cilley.”

- 27

United States Congress, “Death of Mr. Cilley.”

- 28

United States Congress, “Report of the Committee on the Late Duel.”

- 29

United States Congress, “Death of Mr. Cilley.”

- 30

“Duel Between Messrs. Graves and Cilley,” Niles’ National Register (Baltimore, United States: American Periodicals Series II, March 3, 1838).

- 31

Ginn, New England Must Not Be Trampled On, 185.

- 32

Ginn, New England Must Not Be Trampled On, 183.

- 33

“Summary of the Week,” The New England Farmer, and Horticultural Register 16, no. 35 (March 7, 1838): 278.

- 34

“The Late Jonathan Cilley,” Trumpet and Universalist Magazine (Boston, United States: American Periodicals Series II, March 24, 1838).

- 35

“I Had Rather Be in the Place of Cilley, Than of Graves,” Boston Recorder (Boston, United States: American Periodicals Series II, March 16, 1838).

- 36

Freeman, The Field of Blood, 103-5.

- 37

“Twenty-Fifth Congress.: Second Session--Senate. House of Representatives Thursday’s Proceedings.,” Niles’ National Register (Baltimore, United States: American Periodicals Series II, March 3, 1838).

- 38

“Death of Mr. Cilley - Testimony of Respect,” The Sun, February 28, 1838.

- 39

Freeman, The Field of Blood, 101.

- 40

C.A. Wells, “The End of the Affair? Anti-Dueling Laws and Social Norms in Antebellum America,” Vanderbilt Law Review 54, no. 4 (May 1, 2001): 1807.

- 41

United States Congress, “Graves, William Jordan,” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, accessed December 3, 2024, https://bioguide.congress.gov/search/bio/G000392.

- 42

Freeman, The Field of Blood, 198-9.

- 43

Mildred Amer, “Members of the U.S. Congress Who Have Died of Other Than Natural Causes While in Office” (Government and Finance Division of Congressional Research Service at The Library of Congress, March 13, 2002), https://web.archive.org/web/20110110031206/http://www.policyarchive.org/handle/10207/bitstreams/675.pdf.

- 44

Freeman, The Field of Blood, 102-3.

![Capitol Crawl Jennifer Keelan-Chaffins wears a bandana as she crawls up the U.S. Capitol steps on her hands and knees. On her left is a man bending over and on her right a woman moves up the stairs on her back. All three protesters wear matching light blue shirts from the ADAPT organization. In front of them are media personnel with cameras and microphones recording the protest. [Photo Credit: Associated Press]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/Capitol%20Crawl%20AP%20Photo.jpg?itok=3SKhheG1)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)