The Strange Rock of Georgetown: Colonel Ninian Beall

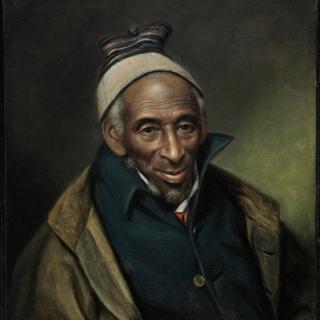

Known by some as the founder of Georgetown, Colonel Ninian Beall was quite an interesting fellow. With fierce red hair he stood 6 feet 7 inches tall and he lived almost 3 times longer than he should have. (The average life expectancy was 35 and he lived to be 92). What a champ.

Born in 1625 in Scotland, Beall spent the first 27 years of his life living out scenes from an adventure film. While fighting in the Scottish Army, Beall was taken prisoner at the Battle of Dunbar and landed in a London prison. Shortly after, he and 149 others were shipped to the island of Barbados in the West Indies to live as indentured servants. Doesn’t sound much like the Caribbean vacations we think of nowadays.[1]

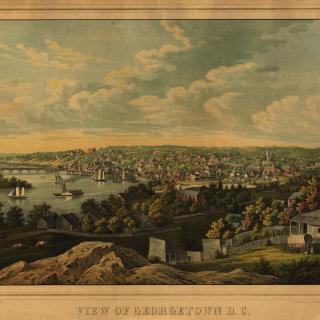

In 1652, Beall entered into another indentured servant arrangement – this time under Richard Hall – and migrated to Maryland. After his term was over, he ended up with a large stretch of land and began to gain power and influence. He became a member of the Maryland House of Burgesses and held a high position in Maryland’s Provincial Forces. He also was one of the first settlers of the area now known as Georgetown, owning nearly 800 acres of land, which he named the Rock of Dumbarton in homage to his home country.

At 42 – an age at which most men of the time were in their graves – Beall married 16-year-old Ruth Moore and fathered twelve children. He then lived for another 50 years. Beall finally died in 1717 at Bacon Hall in Prince Georges County.[2] One relative estimates he has over 70,000 descendents. That would be quite a family reunion.

With such a lineage, it’s no wonder that the legendary Ninian Beall earned himself a monument in Georgetown. It took almost 200 years but on October 30, 1910 hundreds of family members and friends gathered at St. John’s Episcopal Church on O St. NW for a special ceremony. Among the attendees were members of the Society of Colonial Wars, American Clan Gregor, and many relatives of the Beall family. In Ninian’s name, a bronze-plated rock was placed on the lawn of the church. The plaque read: “Colonel Ninian Beall Born Scotland 1625, Died Maryland 1717, Patentee of Rock of Dumbarton, in grateful recognition of his service.”[3]

That’s all fine and good, but not really all that remarkable. After all, we live in a city of monuments and memorials… Yes, but not a memorial quite like this. According to the Washington Post account of the dedication ceremony, the stone mason in charge of the rock hid something special inside the marker:

Few of those attending the services knew that in a hole hidden by the tablet were a number of articles placed there by I.B. Millner who secured and cut the stone. Mr. Millner is an enthusiast on aviation and placed in the hole a photograph of a Curtiss biplane in flight, an editorial on aviation cut from a Washington newspaper, and a program of the exercises and several pictures. He predicts that some time in the far-distant future the stone will fall apart, and future generations will read wonderingly of the beginnings of flying.[4]

Wait, what?

Apparently I.B. Millner really liked airplanes and decided to turn Ninian Beall’s memorial into a homemade aeronautics time capsule. You know, just because… (No word on whether he included anything about the 1903 Langley Aerodrome, but if not he totally should’ve.) Bizarre.

As far as we can tell, Millner was going rogue with this one. There doesn’t seem to be a connection between Ninian Beall and the miracle of human flight. Then again, Beall accomplished a whole lot during his extra-long lifetime. So maybe he was working on a flying machine, too. But probably not…

And so – at least until the rock breaks open – the story ends with a weird guy receiving a rather weird monument filled with some weird articles about airplanes. Like we said before, bizarre.

Footnotes

- ^ Gelders, Ruth Beall. Kim Beall's Beall History Pages, "Colonel Ninian Beall." Last modified 1976. Accessed July 18, 2013. http://www.krystalrose.com/kim/BEALL/ninian1.html.

- ^ Battey, George Magruder. "The Mystery of Ninian Beall's Burial Place Remains Unsolved." Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C.. (1940/1941): 161-167.

- ^ "Beall Rock Unveiled: Memorial Dedicated to Patentee of Georgetown Site." The Washington Post, October 31, 1910.

- ^ Ibid.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)