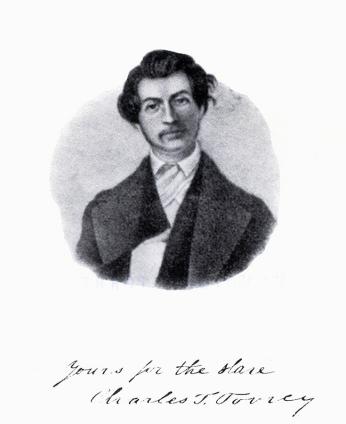

Charles T. Torrey: The "Impulsive" Abolitionist Who Helped Free Hundreds of Slaves

It was January 14, 1842, and Charles Torrey was in trouble. The young white reporter was being chased by a mob of enraged slaveholders in Annapolis, Maryland, after trying to report on their convention for abolitionist newspapers. He’d managed to make it back to the tavern where he was staying, but the angry crowd forced him to pay his bill and began arguing over what to do with him.

“Some were for taking me five miles out of town and letting me go. Others were for tar and feathers, or even hanging. But they were overruled by citizens of Annapolis…and then the Sheriff and others, preceded and followed by a mob of 2 or 300, shouting, yelling and hissing, like so many crazy men, conducted me to the jail.”1

He was safe – for now.

This was Torrey’s first taste of the dangers of abolitionism. Having been born to a prominent family in Massachusetts, he hadn’t spent much time around slaveholders like those who mobbed him in Maryland. His education at Phillips Academy, Yale, and Andover Theological Seminary had also not provided much exposure to the system. During his time at these schools, distant as they were from the battlefield of slavery, Torrey became aware of and dedicated to the abolitionist movement. As he trained to join the ministry, he immersed himself in abolitionism; as one biographer later put it, “Torrey had only one interest – the abolition of slavery – and it had taken possession of his soul.”2

At Andover, Torrey formed an anti-slavery society. After graduation, he organized a split from William Lloyd Garrison’s American Anti-Slavery Society to create the Massachusetts Abolition Society in 1839, the Liberty Party in 1840, and the Boston Vigilance Committee in 1841.3 The split with Garrison was the first indication of Torrey’s belief in action over words. The older abolitionist advocated abstinence from government and politics based on the idea that a system built on and supported by slavery was inherently corrupt. He also firmly condemned helping enslaved people to escape, preferring to win over their masters with moral arguments and then have them legally freed. Torrey could not abide this waiting and lack of action.

No longer satisfied with attending meetings and making speeches, Torrey took it upon himself to move south to Washington, D.C in December 1841. He would be the congressional reporter for several abolitionist newspapers in order to support himself and his family (who stayed behind in Massachusetts) and look for ways to actually free slaves. That’s how he found himself in the Anne Arundel County jail one month later, sharing the space with a family of 13 enslaved people. Their master had freed them in his will, but that will was now being contested by the heirs and the group was forced to await the results of the hearing in custody. Though this was not an unusual case, hearing their story broke Torrey’s heart in a way that no speech ever had. He recommitted himself to the abolitionist cause.

I call my Heavenly Father to witness, that not from malice, but from the dictates of patriotism and benevolence, and from a sense of duty to him, I have made war against slavery; and I call him to witness, that henceforth, seeking his wisdom to guide and his grace to strengthen me, I will not cease to talk, write, preach, pray and vote against slavery, till there is no slaveholder in any church, or any slave in our land. And whatever their errors may be, I will honor and love all who so labor in this cause. When death comes, and then only, will I cease. – Charles T. Torrey4

Torrey was released after only a few days in prison, the judge having found nothing with which to charge him. He packed up and left Annapolis for D.C. to return to his journalistic duties.

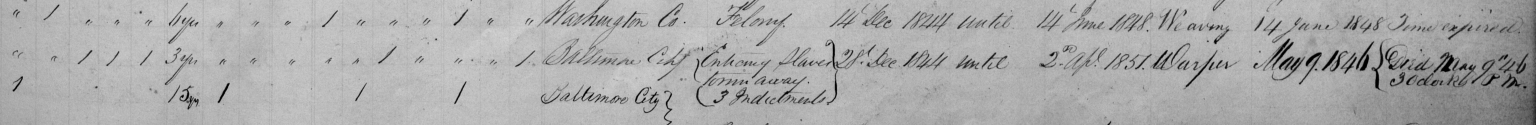

It was at this point that he made a connection that would change his life. A local free black man named Thomas Smallwood got in touch with Torrey through the laundress at Torrey’s boarding house, who happened to be Smallwood’s wife. Smallwood was impressed with Torrey’s actions in Annapolis and wanted to work together to further their common cause of abolition. Torrey, always gung-ho and eager to act, introduced a plan to help free a family that was in danger of being sold south. While that plan never came to fruition, the men began working together to aid the escapes of slaves – sometimes a dozen or more at a time – from bondage in the District of Columbia. Their efforts caused a sensation in Washington.

Torrey hadn’t chosen D.C. by accident. He knew it to be “the focal point of the sectional struggle over slavery” and wanted to strike where it would create the biggest disturbance.5 His plan was “to select slaves from politically high-profile families, including southern congressmen, whenever possible” to force the issue of abolitionism to the front and center of D.C. politics.6

They continued to personally facilitate escapes until 1844 when Smallwood had been forced to flee to Canada with his family as the authorities closed in. As a white man, Torrey was far safer in D.C. He kept leading daring journeys north on his own.

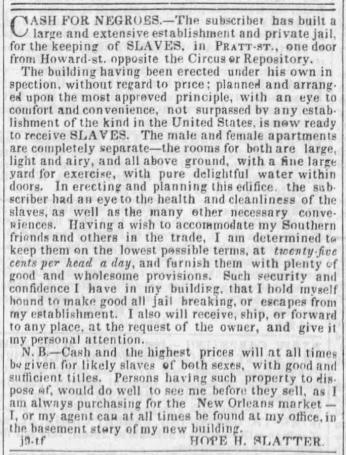

On June 5, 1844 though, Torrey made the trip that would be his undoing. He “had an agency in decoying away” three people from William Heckrotte in Baltimore.7 Torrey rented a wagon and horses to drive the Gooseberry family out of the city. The mother, Hannah, and her two children, Judah and Stephen, made it north, and Torrey thought himself safe as well. He embarked on his next project: freeing a man known as “Big Ben” from Hope Slatter’s slave prison in Baltimore, Maryland.

Slatter recognized Torrey and sent a note to Bushrod Taylor who had been attempting to capture Torrey for months, after the abolitionist had assisted six enslaved people in running from Taylor’s property in Winchester, Virginia. Thanks to Slatter’s tip, Taylor had Torrey arrested. He was thrown in another Maryland jail, this time under a much more serious charge.

Having been described as “[a]ll impulse and imprudence and ostentation,” Torrey continued to live up to his reputation by attempting a jail break.8 Using a mirror to watch for guards, Torrey began sawing away at the iron bars in the windows using tools smuggled into him by his landlady from Washington, D.C., Mrs. Padgett. Four other men hoped to join him in his flight and they made it through two of the four crossed bars before Officer John Hoey burst into the cell. He had heard the sawing from outside and quietly informed the warden. Without alerting the prisoners, a group of guards snuck to the cell and surprised the men at their work. A search revealed several saws, bullets, and gunpowder among Torrey’s things. All involved were put in irons and separated into different cells and Torrey’s trial was quickly moved up to prevent further trouble.9 They had been betrayed by a slave trader named Dryer who was jailed for counterfeiting. Torrey was undeterred, however. As he wrote to his wife, “I deemed it my duty to try once to escape out of the hands of my enemies.”10

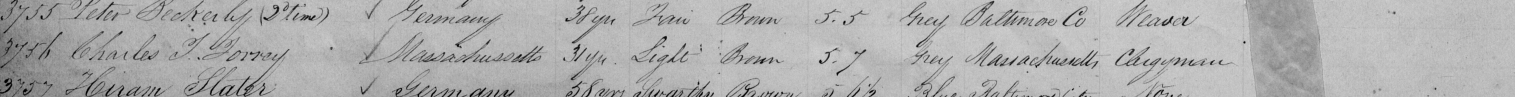

A relatively short trial ended in Torrey being found guilty of “persuading, aiding and abetting in abducting slaves” and sentenced to six years in the Maryland State Penitentiary, the minimum term prescribed by law.11 Torrey had hoped to push the trial to the Supreme Court, as he was indicted in both Maryland and Virginia, but authorities decided to try him in Maryland and withheld the opportunity to make it a national ordeal.

Papers like The Liberator and the Albany Patriot recorded the trial and published letters of support for the incarcerated reverend. While some believed that he had been foolhardy and that he was “likely to meet the reward that is due to him at last,” most called for sympathy and aid:12 “Christian men and women of New England, Charles T. Torrey is dying in a slaveholder’s dungeon. Can we do nothing for him? Must he, for sympathizing with crushed humanity, receive the punishment meted out to murderers?”13

And he was dying. Torrey’s father, mother, and younger sister had all died of tuberculosis before he was four years old and Torrey himself had suffered from it his whole life. The conditions in the Baltimore prison did nothing to improve his health. The cells were often damp and cold and infested with a multitude of pests. As Torrey himself wrote, “We are well supplied with rats and mice, red ants, and mosquitoes…On the whole it is an exceedingly good place to put a sick man to a lingering death.”14

Torrey had never been good with money. As a young man, he bought a library straight out of college, despite the fact that he was already swimming in debt.15 After marrying Mary Ides, the daughter of one of the preachers who taught him, she and their two children had to move back in with her parents more than once to make ends meet while he was in the south fighting slavery. He bought the Albany, New York abolitionist paper, Tocsin of Liberty, and ended up having to turn over subscription payments to a creditor named Mr. Crocker.16 Abolitionists around the country had taken up a collection to pay for Torrey’s expenses and defense during his trial. (Esteemed lawyer Reverdy Johnson – a slaveowner – took up the case. In Torrey-like fashion, the prisoner boasted to his counsel that he had helped one of Johnson’s slaves escape.17) Now, they took up another collection to try to pay his way out of prison. They hoped that, if they could get Heckrotte to agree to accept payment for the Gooseberry family, Governor Pratt would pardon Torrey and allow him to return home either to heal or to die.

Visitors to the prison reported on Torrey’s condition. One writer found him “pale, emaciated and sick…his eyes are dim, his voice hoarse, his spirits depressed.” He added that “His confinement is undermining his constitution, and that he will survive the five long years yet remaining of his sentence, is quite improbable.”18

Mrs. Mary Torrey wrote her own heartfelt letter to Governor Pratt in addition to the official petition signed by several distinguished men. Her plea was full of love for her husband and concern for her children. “His health is failing – his mental faculties are impaired, and unless mercy is extended, he will die or become a maniac ere the term for which he is imprisoned shall have expired.”19

Charles T. Torrey died of consumption in the Maryland Penitentiary at 3pm on May 9, 1846. A few hours later, the warden received Governor Pratt’s signed pardon for the abolitionist. He sent it back.

Torrey was now a martyr for abolitionists around the world. Dozens of newspapers published accounts of his death, a transcription of the funeral service, condemnation of the slaveholders of Maryland, and even amateur poetry memorializing him.

Let Slavery rejoice. This is the day of her triumph. She has another feather in her cap. She has crushed the heart of an innocent man, and her myrmidons cry out for joy – joy such as the demons feel in their successful moments. But the day of retribution will come.20

Torrey’s body was injected with arsenic, a crude but effective enough method of embalming, and shipped back to Boston. The funeral was arranged for May 18th at 3pm. It was to take place at Park Street Church, but one more conflict remained for Torrey. William Lloyd Garrison convinced the church to withdraw permission for the funeral at the last minute due to their old feud. The service was moved to Tremont Temple, where reportedly thousands of people attended, despite the rain. Joseph C. Lovejoy gave the sermon (he would later compile and edit a memoir of Torrey) and the mourners made their way down to Mount Auburn Cemetery to lay him to rest.

Immediately after his death, plans were made for a memorial to be placed at his gravesite. It would be a three-sided obelisk. One side bore an inscription describing Torrey’s arrest, conviction, and death. Another showed a silhouette of a kneeling enslaved woman. The third had a wreath, a portrait of Torrey, a record of the significant dates in his life, and a few of the words he penned while in prison:

“It is better to die in prison, with the peace of God in our hearts, than to live in freedom, with a polluted conscience.”21

After his tragic death in the Penitentiary, “slaveholders in the Chesapeake correctly perceived Torrey’s ‘ghost’ in an upsurge in local slave escapes.” His life’s work inspired abolitionists like William L. Chaplin to carry on the fight against slavery in the nation’s capital, ultimately touching many more lives than Torrey ever knew.

Footnotes

- 1

Charles T. Torrey, “Letter from Rev. C. T. Torrey,” Emancipator and Free American, February 4, 1842, Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers.

- 2

E. Fuller Torrey, The Martyrdom of Abolitionist Charles Torrey (Baton Rouge : Louisiana State University Press, 2013), 88.

- 3

Stanley Harrold, “On the Borders of Slavery and Race: Charles T. Torrey and the Underground Railroad,”Journal of the Early Republic 20, no. 2 (2000): 278.

- 4

Torrey, “Letter from Rev. C. T. Torrey.”

- 5

Stanley Harrold, Subversives: Antislavery Community in Washington, D.C., 1828-1865 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2003), 2.

- 6

Torrey, The Martyrdom of Abolitionist Charles Torrey, 94.

- 7

“Another Arrest,” Liberator, July 5, 1844, Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers.

- 8

Torrey, The Martyrdom of Abolitionist Charles Torrey, 84.

- 9

“Daring and Audacious Attempt of the Rev. Charles T. Torrey to Escape from Jail,”The Baltimore Sun, September 14, 1844.

- 10

Charles T. Torrey, “My Dearest Wife,” Alexandria Gazette, September 27, 1844.

- 11

“A Warning to Abolition Agitators,” Weekly Herald, January 4, 1845, Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers.

- 12

“Disapprovals,”Albany Weekly Patriot, July 31, 1844.

- 13

A. M. C., “Letter to the Editor,”Emancipator and Free American, October 2, 1844, Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers.

- 14

Joseph C. (Joseph Cammet) Lovejoy, Memoir of Rev. Charles T. Torrey Who Died in the Penitentiary of Maryland, Where He Was Confined for Showing Mercy to the Poor (Boston: J.P. Jewett & Co., 1847), 160.

- 15

Torrey, The Martyrdom of Abolitionist Charles Torrey, 30.

- 16

“NOTICE.,”Albany Weekly Patriot, January 2, 1844.

- 17

Harrold, “On the Borders of Slavery and Race,” 287.

- 18

R. G. Lincoln, “Charles T. Torrey,” Liberator, October 10, 1845, Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers.

- 19

Mary I. Torrey, “Petition for the Release of Rev. Mr. Torrey, Mrs. Torrey’s Letter,”Liberator, February 27, 1846, Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers.

- 20

“Torrey Memorials,”Emancipator and Free American, June 3, 1845, Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers.

- 21

“Monument to Charles T. Torrey,” The Baltimore Sun, September 3, 1851.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)