D.C.'s Ties to Freedom Summer

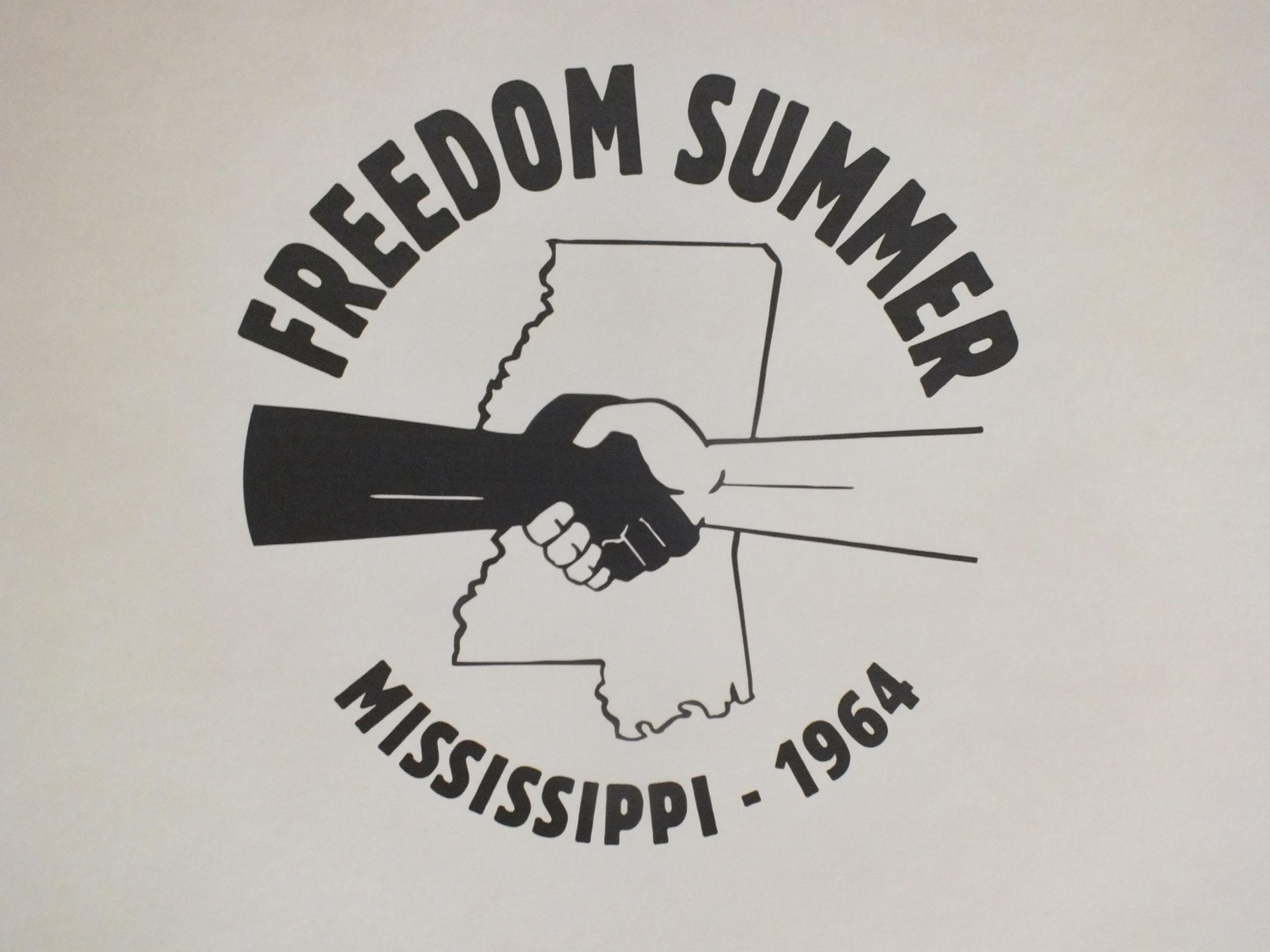

The 1964 Freedom Summer movement in Mississippi is the subject of a new documentary from American Experience. In anticipation of the film, we looked into local Washington area connections to the initiative.

The 1964 Freedom Summer movement in Mississippi does not generally conjure up images of the nation’s capital. But a few of the organizers had strong ties to the District.

Long before Marion Barry became the “Mayor for Life” in Washington, D.C., he was a Civil Rights activist working with the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee.

In 1964, SNCC focused efforts on black voter registration and education in Mississippi, which had the lowest percentage of African-Americans registered to vote in the country (a startling 6.7% as of 1962). The group recruited hundreds of volunteers from college campuses across the nation to come to the state to canvass.

Marion Barry worked as a field secretary in Mississippi along with SNCC leader Bob Moses. At the time, the state’s Democratic party was limited to whites only. To expand black political participation, Moses and others founded an alternative caucus, which they called the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. Barry then took on the job of promoting the new non-discriminatory party throughout the country.

As Barry remembered in 2011, “We had a division of SNCC between direct action and voter registration. But we decided those who wanted to do direct action, do that, those who wanted to do voter’s registration do that. We were all field secretaries for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.”[1]

“I stopped in Greenwood first that’s where we had our first major project. And I took the bus with Reggie Robinson… and we went to McComb,” Barry said in an interview with Telling Their Stories. “We had this philosophy in SNCC of living with the local people. Not living in the hotels, not living in the motels, but with the people. If you live with the people, they will protect you.”[2]

Protection and personal safety was a very real concern. While the state motto claimed Mississippi was “The Hospitality State,” it was anything but that in the summer of 1964. Racism was entrenched and many in the white community sought to intimidate the volunteers with violence.

Just days before the Freedom Summer voter registration movement was set to begin, civil rights workers James Chaney, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman disappeared outside of Philadelphia, Mississippi. In an area known for Klan activity, many feared the worst. Federal investigators and the national media flocked to the area. When the murdered bodies of Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman were discovered buried in an earthen dam weeks later, these fears were confirmed.

As SNCC Field Secretary Charles E. Cobb, Jr., explained, the killings were “an example of what we had really been talking to volunteers about before the three were missing, that you are going in to a murderously violent state and you have to understand that the danger affects you every day, all day long.”[3]

Linda Wetmore Helpern, a volunteer during the campaign remembered, “The vile and absolute hatred that was in their eyes when they saw us coming… it scared me.”[4]

The violence continued over the course of the summer. 70 homes and community centers were bombed. 35 churches were burned.[5] Workers were beaten, the victims were too numerous to be accounted for.

But, despite the dangers, the workers pressed on.

Cobb, who was born in the District and attended Howard University, spearheaded the development of “Freedom Schools,” a network of 30 to 40 voluntary schools that worked to help African-Americans articulate their demands.

“Negro education in Mississippi is the most inadequate and inferior in the state,” Cobb wrote in his Freedom Schools proposal in 1963. “Mississippi’s impoverished educational system is also burdened with virtually a complete absence of freedom, and students are forced to live in an environment that that is geared to squash intellectual curiosity, and different thinking.”[6]

The Freedom Schools operated on a basis of close interaction and mutual trust between teachers and students. The core of the curriculum focused on black history, literacy, civil rights, political processes, arithmetic, and the summer freedom movement.

Pam Parker, a teacher in the Holly Springs School wrote about the experience, “The atmosphere in the class is unbelievable. It is what every teacher dreams about — real, honest enthusiasm and desire to learn anything and everything. The girls come to class of their own free will. They respond to everything that is said. They are excited about learning. They drain me of everything that I have to offer so that I go home at night completely exhausted but very happy in spirit..."[7]

The aftermath of Freedom Summer ultimately did not result in registering many African-Americans to vote, but its impact in the civil rights movement was seen and felt.

“The most amazing thing about that summer is this: We Won,” reflected Bob Mandel, a civil rights worker in Clarksdale, Mississippi. “Not then, but eventually. And when we got to Mississippi, we didn’t know that. We could have brought more trouble to these people than it was worth.”[8]

For more on the Freedom Summer of 1964, be sure to check out the documentary from American Experience.

Footnotes

- ^ “Mr. Marion Barry.” Telling Their Stories: Oral History Archives Project. 24 Mar 2011.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “50 Years Ago, Students Fought For Black Rights During ‘Freedom Summer.’” Jun 23 2014. wypr.org.

- ^ Dawidsiak, Mark. “‘Freedom Summer’ takes in-depth look at 1964 Civil Rights battle in Mississippi.” Cleveland.com.. Accessed Jun 21 2014.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Cobb, Charles. "Prospectus for a Summer Freedom School Program in Mississippi.”

- ^ Mississippi Freedom Summer-- 1964. Civil Rights Movement Veterans. Cmvet.org.

- ^ Booth, William. “Reflections of Freedom Summer; In '64, They Battled Racism in Mississippi. This Weekend, They Returned to See the Result.” The Washington Post. 27 Jun 1994.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)