“The best Southern cook this side of heaven”: How Zephyr Wright Helped Pass the Civil Rights Act

President Johnson was used to getting what he called “love notes” with his dinner. They listed the number of calories and the amount of each macronutrient he was about to eat - a sensible practice after his heart attack in 1955 and a lifetime of eating traditional southern food. What he wasn’t used to were the orders that came with it on this particular night.

“Mr. President, you have been my boss for a number of years and you always tell me you want to lose weight, and yet you never do very much to help yourself. Now I am going to be your boss for a change. Eat what I put in front of you, and don’t ask for any more and don’t complain.”1

The message was from his cook, Zephyr Wright, a Texas woman who had been serving the Johnson family for over 20 years. Johnson later showed the note to Senator J. William Fulbright, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Fulbright had accused Johnson of an “arrogance of power” in how he was handling the Vietnam War. “‘If and when I feel arrogance of power,’ he reassured the doubting Senator, ‘Zephyr will take it out of me.’”2

Zephyr Wright attended Wiley College in Marshall, Texas in the 1940s. That was where Mrs. Lady Bird Johnson found her in 1942. Mrs. Johnson approached Dr. Dogan, the president of Wiley, looking for a new cook for her family. Wright was in her last semester of a home economics degree and Dogan recommended her to the future First Lady as an excellent cook and a hard worker. Wright was excited at the opportunity to join the Senator and his wife in Washington “because I knew I’d never have an opportunity to go anywhere.”3 This was her chance to see more of the world.

Mrs. Johnson drove to Wright’s home to conduct the interview. “We just talked,” Wright later said, “and in about fifteen or twenty minutes she had hired me.”4

Mrs. Johnson drove Wright and one other household employee up to Washington in her car. The trip was long enough that they had to stop somewhere to stay the night, which turned out to be a more difficult venture than Lady Bird had anticipated. She was, after all, a wealthy white lady. No one ever turned her down. In Memphis, Tennessee, “we stopped at a place, and Mrs. Johnson asked them about a place to stay. The woman said, ‘Yes, we have a place for you.’ She said, ‘Well, I have these two other people,’ She said, ‘No. We work ‘em but we don’t sleep ‘em.’ And Mrs. Johnson said, ‘That’s a nasty way to be,’ and she drove away.”5 That wasn’t the last time the Johnsons would vicariously experience the racism still rampant in America through their new cook.

In D.C., Wright’s cooking soon made her something of a celebrity. The Johnsons loved to host dinner parties and their friends were all high-ranking politicians. They never asked Wright to make the fancy European dishes which became popular when Kennedy took the White House. Her deep south recipes were exactly what they wanted. Newspapers raved about “the queen of the private kitchen on the second floor of the White House, and the much-admired producer of such high-calorie goodies as chocolate souffle, fresh fruit ice cream, brownies, spoon bread, popovers, and tapioca pudding.”6 Sam Rayburn, Speaker of the House, called Wright “the best Southern cook…this side of heaven.”7

The acclaim only grew after Kennedy’s assassination and Johnson’s promotion to President. Everyone wanted to know what the Johnsons were like at home - and especially what they ate. Wright gave numerous interviews, allowing the public a window into the lives of the Johnson family as they planned for their first Thanksgiving in the White House: “Mrs. Wright, who got a turkey only yesterday, indicated the meal would be in the traditional Thanksgiving way with such Southern touches as cornbread dressing, whipped sweet potatoes and an ambrosia desert [sic] of orange sections, pineapple and coconut.”8

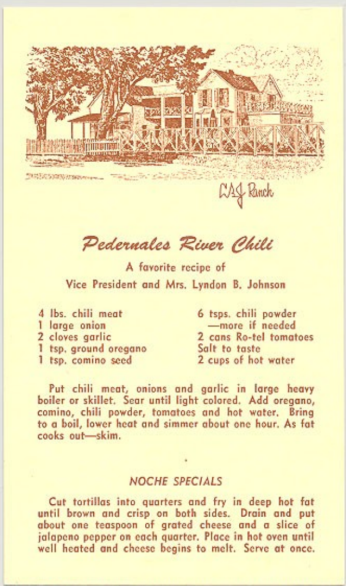

Zephyr Wright was more than just a really good cook though. She is not remembered today for her popovers, Pedernales chili, or homemade bread (which some of the Johnsons’ dinner guests said could make the family a fortune if they franchised its distribution9). Mrs. Wright went down in history because of how she managed to shape monumental civil rights legislation from her place behind the kitchen counter.

Wright’s Memphis, Tennessee encounter on her way to the White House was far from the last time she experienced discrimination and racism while serving the Johnsons. Things were a little better in D.C., where people knew her, but Johnson often asked her and Gene Williams, another black house servant, to drive down to Texas. Wright remembered one time that Johnson wanted them to take his beagle with them in the car while the family flew. “[W]e didn’t want to take the dog. He couldn’t understand why we didn’t want to take the dog, so we told him that it was hard enough for us to find a place to stay and get across the country, let alone taking a dog. We just couldn’t afford to take that dog.”10 Eventually, she refused to leave D.C. anymore. This devastated the President and his family who had to put up with someone else’s cooking during their visits home. Lady Bird always noted in her diary when “Zephyr was off and dinner was not up to par.” “She’s hard to get along without,” she added.11

Never afraid to do what had to be done to accomplish his goals, President Johnson used Wright’s travel experiences to win over business executives, friends, and politicians alike to support the Civil Rights Act. He called her “one of the great ladies that I have known…She has been with us twenty years, she is a college graduate, but when she comes from Texas to Washington she never knows where she can get a cup of coffee. She never knows when she can go to a bathroom. She has to take three or four hours out to go across the other side of the tracks to locate the place where she can sit down and buy a meal. You wouldn’t want that to happen to your wife or your mother or to your sister, but somehow or other you take it for granted when it happens to someone way off there.”12

Another time, Mrs. Wright fell in the snow on her way home from work. Lady Bird remembered the event in an interview later in life. “[O]ne of the neighbors went out and put blankets over her and called an ambulance. And there was a bad little time when the ambulance–somehow or another the people said that this was a cook for one of their neighbors, and they asked if it was a black woman, and they wouldn’t come and pick her up. Fortunately she was quite conscious. She told them who she worked for. We got up there as quick as we could. We did get an ambulance, but I just remember how startled and angry I was.”13

Mrs. Johnson might have been angry and President Johnson might have used her stories to win constituents and votes, but Mrs. Wright just kept working. Wright was as invested as anyone in the Civil Rights Movement raging around her, but she didn’t feel that she could join in the traditional way. She even stayed home during the March on Washington. “I think working for the Johnsons I didn’t associate myself with any of these things that were going on. I kept it on TV, and President Johnson would come in and say, ‘Did you see or hear what went on today?’ And I said, ‘Yes.’ Then we’d sit down, and we’d talk about it. He just seemed happy about what was going on. He said, ‘Well, this is a step forward for you people.’”14

Wright may not have been able to march, but that conversation with Johnson was just one of many ways she found to fight for equal rights quietly and within the White House itself. She used her own life and experiences to make Johnson understand what other Black people were going through at the time. At one point, she asked for a raise. After the French chef hired by the Kennedys left “in a huff over the Johnsons’ weakness for such indelicacies as frozen vegetables,” Wright was left to pick up the slack while they looked for a replacement.15 When they did find a new chef, Wright soon realized that she was more experienced than he was and yet was making less money. “I do think with my talk with him about salaries for the Negro I talked to him about myself, really, and in talking with him about my salary made him conscious of what the other Negro people were going through.”16

It may not seem like a lot, but talking to President Johnson was no easy prospect. The man was known for being difficult and for his quick temper. Wright knew how to handle his mood swings though:

“Now, he could talk to you this minute, and he would just kind of cuss you out. He really didn’t cuss you out, but he would give you down the country or something. And the next minute he was putting his arms around you and was hugging you and telling you how much he loved you. But you had to be straight with him. You see, I guess I was always so outspoken until if he talked to me, whatever he would say to me, I would say right back to him. He liked that, I think, better than cowering and bowing - he didn’t care for that.”17

President Johnson also made a habit of arriving for meals several hours late and with dozens of unexpected guests in tow. “Now there have been times that he’d get on the phone himself and call me and ask me how long would it take me to get something ready for the whole Cabinet. And sometimes he would walk in with them, and you didn’t even knew he was coming. It was just amazing…I’ve seen times that I have fixed a meal in ten minutes for twenty-five or thirty people.”18 Wright developed a system for dealing with these last minute requests. She had the butlers serve sherry while she prepared the soup. As the guests ate the soup, she quickly cooked the meat and vegetables. “Fortunately we always have something on hand for such cases,” she said in one interview.19

As adept as she was at dealing with Johnson’s antics, by the time he was preparing to leave office, Wright was also ready to retire. She had gained 80 pounds in her time at the White House and as she looked after the President’s health, her own was beginning to fail.20 She gave a handful of interviews exposing the difficulties of working for Johnson. The New York Times summed it up well: “Even the President’s most passionate critics must be aware that there is an ancient principle at work here which may account for the unusual vigor of Mrs. Wright’s hostility. Simply stated, it is that Hell hath no fury like that of a woman asked to keep a meal viable for three and a half hours after it was meant to be served.”21

Though Wright remained behind in D.C. as the Johnsons moved back to Texas, her legacy would live on in the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The way she lived her life had rubbed off on the inimitable Johnson. She had the honor of witnessing the signing of the Act. Handing her one of several pens he used, President Johnson told Zephyr Wright, “You deserve this more than anyone else.”22

President Johnson is, like many presidents, a controversial figure. Much of his staff (and the country) did not especially like him. But Mrs. Wright held a special place for him in her heart. She cried when he chose not to run for president again “because I had never seen him give up before on anything. He had always been such a fighter.”23 She watched his speeches on TV - except for those she was invited to hear in person. To Wright, “he was not a president; he was just another person,” and “he seemed more like a brother to me than anything else, because once I got to know him he was just that way.”24 Years after Johnson’s death, she told an interviewer, “To me he was just the best. He was just the greatest.”25 But none of his greatness would have been possible without her tireless work to both feed and advise the President of the United States.

Note: Zephyr Wright gave an oral history interview for the Lyndon Johnson Presidential Library in 1974. If you want to read more stories of her quiet fight for civil rights and anecdotes of her time with Johnson (several of which are funny, shocking, and, quite frequently, both), you can get the transcript here.

Footnotes

- 1

Nona Brown, “Johnson and His ‘Boss,’” The New York Times, May 8, 1966.

- 2

Brown, “Johnson and His ‘Boss.’”

- 3

Michael L. Gillette, Oral History Transcript, Zephyr Wright, December 5, 1974, LBJ Presidential Library, 4.

- 4

Gillette, Oral History Transcript, Zephyr Wright, 5.

- 5

Gillette, Oral History Transcript, Zephyr Wright, 6.

- 6

Brown, “Johnson and His ‘Boss.’”

- 7

Eric Frederick Goldman, The Tragedy of Lyndon Johnson (New York : Knopf, 1969), 351.

- 8

“First Family Plans Quiet Turkey Dinner,” The Evening Star, November 28, 1963.

- 9

Marie Smith, “Zephyr’s Delectable Homemade Bread Will Still Grace LBJ’s Table,” The Washington Post, December 1, 1963.

- 10

Gillette, Oral History Transcript, Zephyr Wright, 42.

- 11

Lady Bird Johnson, A White House Diary (New York : Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1970), 168, 594.

- 12

Goldman, The Tragedy of Lyndon Johnson, 70.

- 13

Michael L. Gillette, Oral history transcript, Lady Bird Johnson, January 30, 1982, 19, LBJ Presidential Library.

- 14

Gillette, Oral History Transcript, Zephyr Wright, 11.

- 15

“Heat in the Kitchen,” The Washington Post, December 2, 1968.

- 16

Gillette, Oral History Transcript, Zephyr Wright, 14.

- 17

Gillette, Oral History Transcript, Zephyr Wright, 15.

- 18

Gillette, Oral History Transcript, Zephyr Wright, 27.

- 19

Marie Smith, “Zephyr Wants Out Of the Kitchen,” The Washington Post, November 28, 1968, sec. For And About Women.

- 20

Smith, “Zephyr Wants Out Of the Kitchen.”

- 21

“Heat in the Kitchen.”

- 22

Adrian Miller, The President’s Kitchen Cabinet: The Story of the African Americans Who Have Fed Our First Families, from the Washingtons to the Obamas (University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 119.

- 23

Gillette, Oral History Transcript, Zephyr Wright, 45.

- 24

Gillette, Oral History Transcript, Zephyr Wright, 39, 17.

- 25

Gillette, Oral History Transcript, Zephyr Wright, 47.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)