The French Ambassador Was Teddy Roosevelt's Hiking Buddy

In Rock Creek Park, there's a granite bench on the trail near Beach Drive, just south of Peirce Mill, that bears a curious inscription: "Jusserand: Personal tribute of esteem and effection."

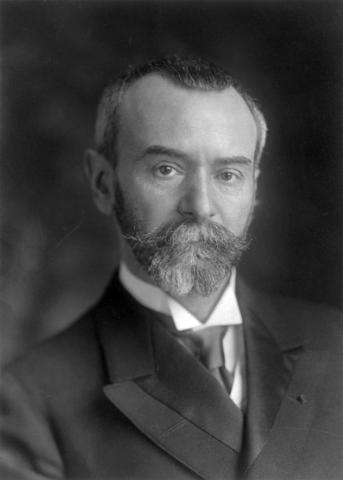

It's a safe bet that most of the people who pass by the odd little 78-year-old memorial don't realize that it commemorates one of President Theodore Roosevelt's close friends, French ambassador Jean Jules Jusserand (1855-1932), who spent numerous afternoons hiking with the 26th President in Rock Creek Park. Historian Scott Einberger notes that the Gallic diplomat reportedly was one of few people in Washington who could keep up with Teddy on a hike, but as Jusserand himself admitted in his memoirs, that was no easy feat: "What the President called a walk was a run: No stop, no breathing time, no slacking of speed, but a continuous race, careless of mud, thorns and the rest."

Jusserand's initial hike with Roosevelt was a particularly arduous one. As Roosevelt biographer H.W. Brands details, the diplomat showed up at the White House that day in an afternoon coat and silk hat, imagining that Roosevelt's idea of a walk might be something like taking a stroll in the Tuileries. Instead, TR appeared in knickerbockers, heavy boots, and a battered felt hat. With a few other hikers, the pair then embarked on a march out of the city and into the woods. Roosevelt hated to stay on trails, and preferred point-to-point hiking that required carving out his own route. Pretty soon, Jusserand's elegant attire was splattered with mud, but he neverthess managed to keep up. As a boy, he'd spent summers traipsing about in the forests on the slopes of the Monts de la Madeleine, and he was still in pretty good condition.

According to various accounts, at one point, the hikers arrived at Rock Creek or another stream, and Roosevelt startled the Frenchman by stripping off his clothes, explaining that he wanted them to be dry when he got to the other side of the stream. The ambassador reluctantly followed Roosevelt's lead. "I too, for the honor of France, removed my apparel, everything except from my lavender kid gloves," he later recalled. He explained to a puzzled Roosevelt that the gloves would help him stave off embarrassment "if we should meet ladies" before they had a chance to put their clothes back on.

Roosevelt apparently was charmed by Jusserand's sense of humor, as well as by his toughness. The two men embarked upon what became a close friendship, both personally and professionally. As historians Hans Krabbendam and John M. Thompson note, the French ambassador became the most important member of Roosevelt's "tennis cabinet" of informal advisors and confidantes: "Roosevelt made a point of consulting Jusserand as if he were an honorary cabinet officer, and told a bewildered Congressman, 'He has taken the oath as Secretary of State.'"

The Roosevelts: An Intimate History, a film by Ken Burns, chronicles the the lives of Theodore, Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, three members of the most prominent and influential family in American politics.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)