The Library of Congress: An Overdue Opening

November 1, 1897 was a cold, rainy Monday in the District. “This may not have been propitious weather for some occasions, but it was hailed with delight by a certain class of persons when they arose [that] morning. They were not human ducks, either, for the affair in which they wished to participate was sufficient evidence that they were intensely human, and of an intellectual type.”[1] This was the day that the new Congressional Library was to open, and allow eager readers into the Beaux-Arts style building for the first time. Those readers who had been regulars at the old Congressional Library in the Capitol Building patiently awaited this opening day, as the old Library had been closed since July 31 in order to allow the books to be transferred to the new library. But that Monday morning, the wait for the Library was finally over, and “the rain did not come amiss to the bookworms, but rather served to heighten their enjoyment for the literary feast provided for them.”[2]

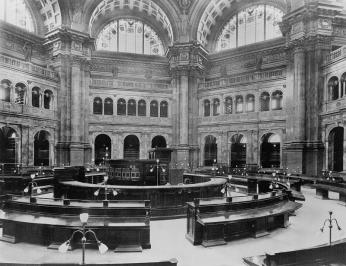

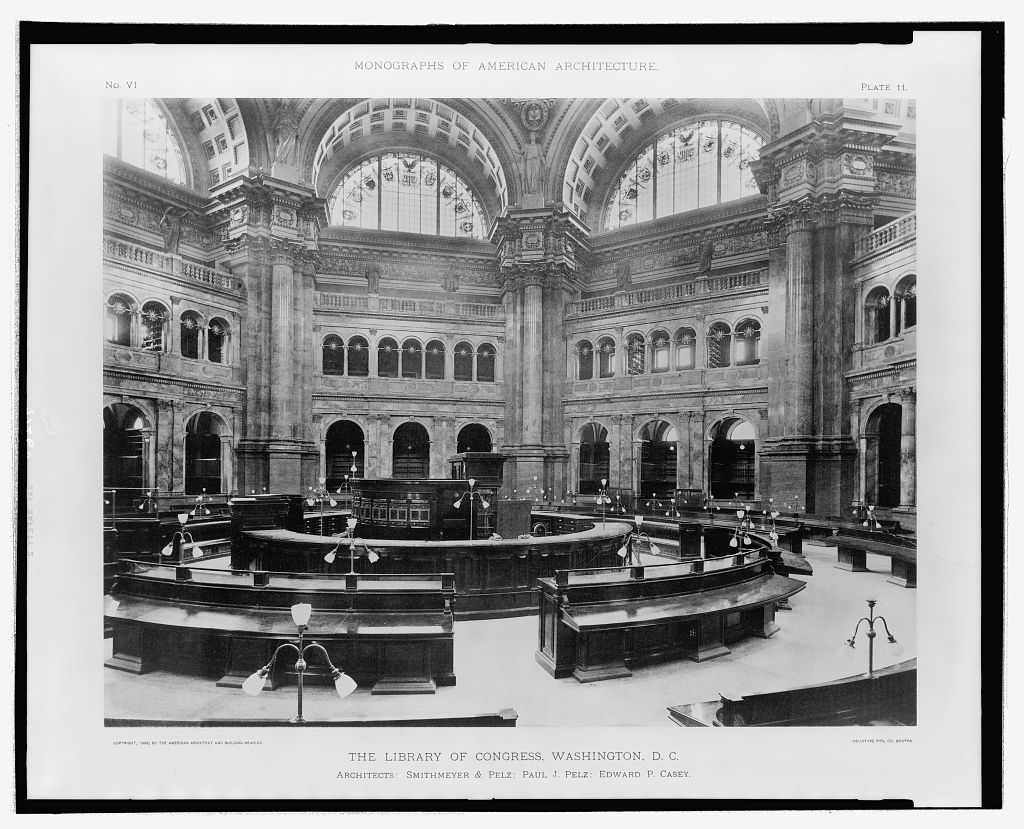

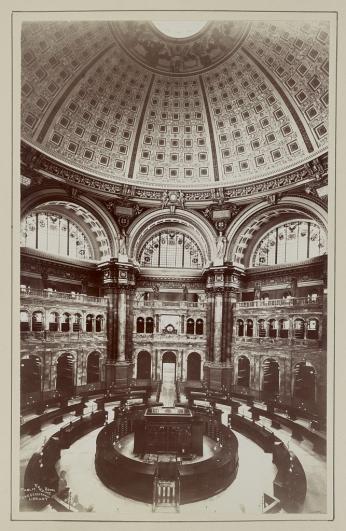

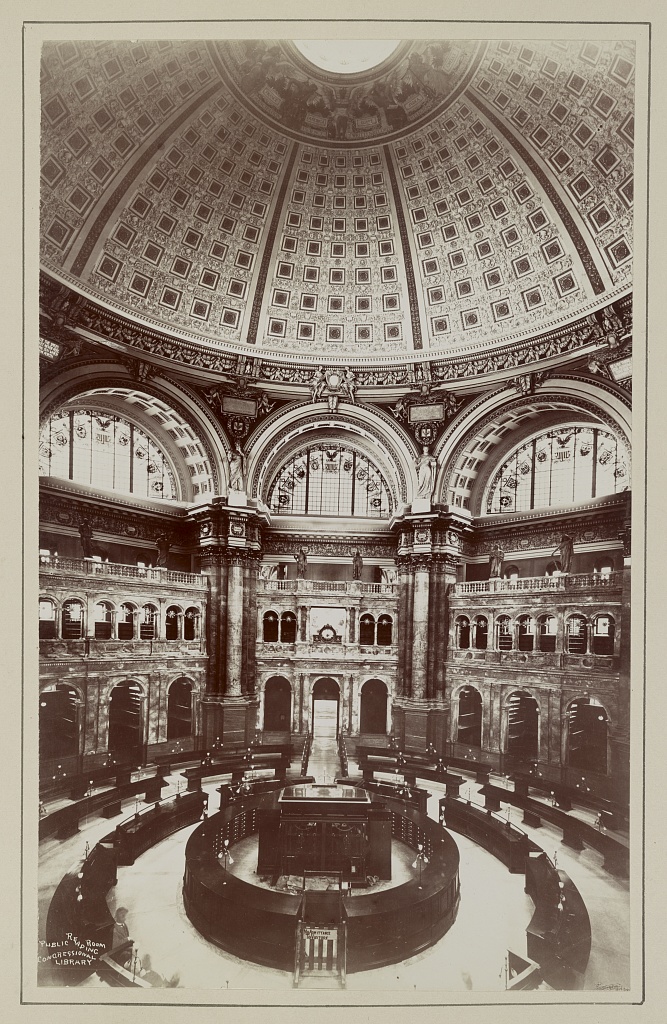

The new Library, featuring “architecture, sculpture, and painting on a scale unsurpassed in any American public building,” opened at 9 o’clock in the morning.[3] Visitors were greeted by watchmen upon approaching the entrance to the reading room, who asked whether or not the visitors intended to “divert and at the same time improve their minds by delving in the volumes of lore which [were] available by applying at the desk of the superintendent.”[4] If the visitor did intend to read, entrance was granted, otherwise, entrance was denied. The Evening Star explained why this action was taken:

“The reading room is no longer intended to satisfy the curiosity of strangers in the capital. No conversation is permitted there. Outside the door was a sign which read: ‘For Library Readers Only.’ On the right of the entrance was a card, on which was printed in bold, black letters the admonition, ‘Keep quiet.’” [5]

Once the bona fide bibliophiles entered the reading room, they were met with a sight unmatched by any other display of American architecture. The style, though classified as Beaux-Arts today, was considered Italian-Renaissance when the building was opened. The design was theatrical, heavily ornamented, and constructed of “15 varieties of marble, 400,000 cubic feet of granite, bronze, gold, and mahogany.”[6] The reading room, a space organized with curved reading tables surrounding the Superintendent’s circulation desk in the center, featured a 23-carat gold plated dome which “capped an elaborately decorated façade and interior which were enriched by the works of about 50 American artists.”[7]

Modern day visitors to the Library reading room might recall the presence of 16 bronze statues who represent accomplished men of their respective categories of knowledge (Philosophy, Art, History, Commerce, Religion, Science, Law, and Poetry). On this opening day, however, visitors would have only seen 14 of those statues standing in place, with Columbus and Michelangelo missing in action. Paul Bartlett was the 32-year-old Connecticut painter and sculptor who was tasked with designing both statues. Previously, he had studied under Rodin, and sculpted the Louvre’s equestrian statue of Lafayette.[8] Bartlett, however, had failed to fulfill his contract with the Library, as neither statue was complete by opening day. Library Superintendent Bernard Green was extremely frustrated with Bartlett, and chewed out the artist upon arriving with Columbus on November 20, 1897.[9] Bartlett was so angry with Green’s admonishment that he stormed out of the building and did not return to speak with Green. Unsurprisingly, Michelangelo didn’t arrive until December 22, 1898—over a year later.[10]

Despite the two missing statues, the reading room was truly a unique work of art for the first-time visitors to experience. It was of generally universal opinion that with the new Library of Congress, “the United States had ‘proved’ that it could surpass any European library in grandeur and devotion to classical culture.”[11] In fact, one visitor, Joseph E. Robinson, told the Librarian of Congress, “Not until I stand before the judgement seat of God, do I ever expect to see this building transcended.”[12]

Just three minutes after the first visitors had entered the new library, the first book, Roger Williams’ Year Book, was requested at the Superintendent’s desk, but the book was so recently published that the Library did not have it. The first book to be successfully requested and given out was Martha Lamb’s History of New York City, and the next was Lady Eastlake’s Memoirs.[13]

To borrow a book, visitors first had to fill out and sign a slip called a “reader’s ticket,” with the title and author of the book they wanted. Once the slip was filled out, it was sent through a series of pneumatic tubes in the library which connected to various stacks and floors of books, where attendants would pull the book and send it down to the reading room floor within approximately five minutes.[14] The book carrying apparatus installed throughout the library, involving these pneumatic tubes and mechanical “carriers,” which bore resemblance to grain threshing machines, operated in much the same fashion as the underground book transfer apparatus connected to the Capitol building.

Old regulars filled the reading room with an exhilarating silence as they enjoyed what the new library had to offer.

“There was the old gentleman, with the long white whiskers, who read his favorite volume through fold-bowed glasses. Another was the fair, young girl, tailor-made, with a taste for light literature and caramels sandwiched. The scholarly looking man, with the high forehead and long black hair, with other characteristics which marked him as the theological student, was in evidence.” [15]

To further accommodate these regular readers, the Library’s intentions for the coming weeks were to have rubber matting installed on the reading room floor to avoid any sound of “scraping feet on the floor.”[16] Readers could also look forward to the arrival of specially made chairs for the reading desks which were slowly but surely making their way to the new building. Having comfortable chairs in the reading room would be important, as it was a “forgone conclusion” that readers would not be allowed to take any books from the reading room—“no matter how a would-be purloiner may plot and scheme to such an end.”[17]

In the coming weeks after the Library’s opening, this new policy on book borrowing faced some backlash. In one letter to the editor of the Evening Star, a man explained that he worked a 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. job Monday through Saturday, which meant that he was never able to take advantage of the Library’s benefits, as they were closed on Sundays and no longer allowed patrons to borrow books.[18] He knew that many working men in the District faced the same dilemma and he hoped that the Librarian of Congress would consider altering the hours to accommodate the working class—a request that would later become a topic of major debate for the Library, and result in a short period of time in which they would be open during the night.

Despite the criticisms and accommodations that the new Library was faced with as the months and years went on, its beauty has, for over 100 years, continued to fill visitors with as much awe as its very first readers experienced in 1897. It was perhaps Mary Simmerson Logan who explained the wonder of the new Library of Congress best:

“The new Library of Congress is a monument of a nation which has emerged from the darkness of doubts and dangers, into the full glory of conscious power. Every stone in the Capitol was the promise of a nation yet to be; every stone in the Library of Congress is the symbol of fulfillment.” [19]

Footnotes

- ^ The Evening Star. 1897. “Library Now Ready,” November 1, 1897. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/resources/search/nb….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Cole, John Y. 1972. “Library of Congress Information Bulletin.”

- ^ The Evening Star. 1897. “Library Now Ready,” November 1, 1897. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/resources/search/nb….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Thomas Jefferson Building.” 2015. Architect of the Capitol | United States Capitol. 2015. https://www.aoc.gov/capitol-buildings/thomas-jefferson-building.

- ^ Cole, John Y. 1972. “Library of Congress Information Bulletin.”

- ^ Helen-Anne Hilker. 1972. “Monument to Civilization: Diary of a Building.” Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress 29 (4). https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951d02974616j. 256-257.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Cole, John Y. 1972. “Library of Congress Information Bulletin.”

- ^ Cole, John Y., Henry Hope Reed, and Herbert Small. 1997. The Library of Congress: The Art and Architecture of the Thomas Jefferson Building. W. W. Norton & Company. 66.

- ^ The Evening Star. 1897. “Library Now Ready,” November 1, 1897. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/resources/search/nb….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ B. 1897. “The National Library - Letter to the Editor.” Evening Star, November 22, 1897, sec. Letters to the Editor. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/image/v2%3A13D5DA85AE05A3….

- ^ Logan, Mary Simmerson (Cunningham). 1901. Thirty Years in Washington of Life and Scenes in Our National Capitol. Hartford, Conn., A.D. Worthington & co. http://archive.org/details/thirtyyearsinwa00loga. 418.

![“Students in the Reading Room of the Library of Congress with the Librarian of Congress, Herbert Putnam, watching” (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Johnston, Frances Benjamin, photographer. Students in the Reading Room of the Library of Congress with the Librarian of Congress, Herbert Putnam, watching. Washington D.C, 1899. [?] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/98502945/. “Students in the Reading Room of the Library of Congress with the Librarian of Congress, Herbert Putnam, watching” (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Johnston, Frances Benjamin, photographer. Students in the Reading Room of the Library of Congress with the Librarian of Congress, Herbert Putnam, watching. Washington D.C, 1899. [?] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/98502945/.](/sites/default/files/styles/embed_full_width/public/3a07924v.jpg?itok=mNkhV93W)

![“Washington D.C., Library of Congress 1897-1910.” (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Detroit Publishing Co., Copyright Claimant, and Publisher Detroit Publishing Co. Washington, D.C., Library of Congress. District of Columbia United States, Washington D.C, None. [Between 1897 and 1910] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016796190/](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/4a28645v.jpg?itok=WxMtjKxx)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)