Joan Mulholland: Arlington's Homegrown Activist

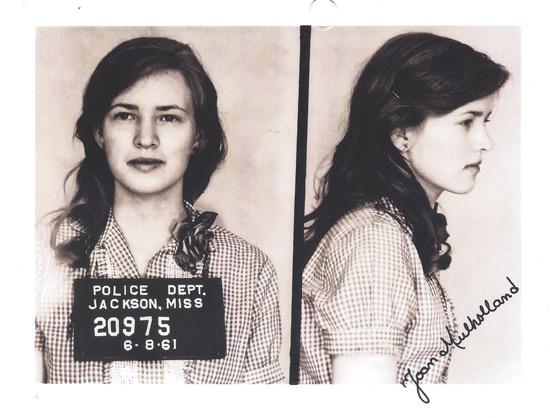

By the time she was 23, Joan Mulholland had participated in more than fifty sit-ins and protests. She was a Freedom Rider, a participant in the near riotous Jackson, Mississippi Woolworth Sit-in, and helped plan and organize the March on Washington in 1963. On a local level, she was part of the first Arlington sit-ins, which integrated lunch counters across northern Virginia, and helped to coordinate demonstrations at Glen Echo Park, Bethesda's Hiser Theater amongst other locations.

Joan Mulholland was born in Washington, D.C. in 1941, the daughter of a Midwestern father and a Southern mother. She grew up in Arlington, Virginia at a time when whites and blacks had very little contact. "We had absolutely no contact with Arlington's African American community back then except perhaps folks that were laborers, trash men... I don't really remember specifically but people that did the cutting the grass, picking up the trash were probably black. And there were maids that would come in, cleaning ladies, into the apartments from Washington, D.C., I believe. But it was a segregated way of life."

Despite the distance, young Joan recognized "the wide discrepancy in conditions for blacks and whites in the South," and had trouble reconciling it with the lessons that she had been taught at school and church. "What we learned in Sunday school and in government class – 'We hold these truths to be self evident' – we were not practicing what we preached and I thought we should. So, in 1960, with the sit ins there was my chance."

While attending Duke University, she participated in her first sit-ins and was arrested twice, a fact that did not please the university administration. After dropping out of Duke in 1960, she returned home to Arlington and help the local Civil Rights effort spearheaded by the Non-violent Action Group based at Howard University. Then, in 1961, Mulholland answered the call for the jail-in in Rock Hill, South Carolina, and, later, the Freedom Rides, which took her to Mississippi.

Her identity as a white woman in the movement created both opportunities and risks, as she told us in our interview:

"You had to use what you had. I could use my white skin to go into a lunch counter, sit down and get a lot of food and then when my black friends sat down next to me I could pass some over. I could go scope out a situation without being conspicuous. I mean I was a sweet young thing back then. I could be what we called a spotter at a demonstration. I could blend into a crowd and have my money, back before cell phones, have my dimes to phone back to the central location – the NAACP office or whatever. I could phone back and give a report. 'Things are calm. Things are getting out of hand. So-and-so just got pulled, beaten. They've been arrested and taken off.' That was a role.

"I could buy the tickets to get into Glen Echo.... Only whites could walk in and you had a have a ticket in hand to get on the ride. Well, on the merry-go-round, they went around and collected the tickets after you were on. They don't do that anymore. But, when it was strategic, my white skin could come in very handy. Other times it could be an endangerment and I was riding on the floor of the car with a blanket over me and people's feet on top of that. But... I was part of the movement by invitation of the blacks. So, it wasn't like I was busting into somebody else's party. I wasn't party crashing. But, pretty much we were all in danger."

Fascinating stuff, for sure, but Joan Mulholland's story is much too deep to cover in a short video and blog post. So check out An Ordinary Hero, a film about Joan, which was directed by her son, Loki.

NOTE: This post was originally written in advance of Joan Muholland's October 2014 presentation to the Arlington Historical Society.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)