In the 1960s, Prison Chaplains Created a Star Studded Music Festival at Lorton Reformatory

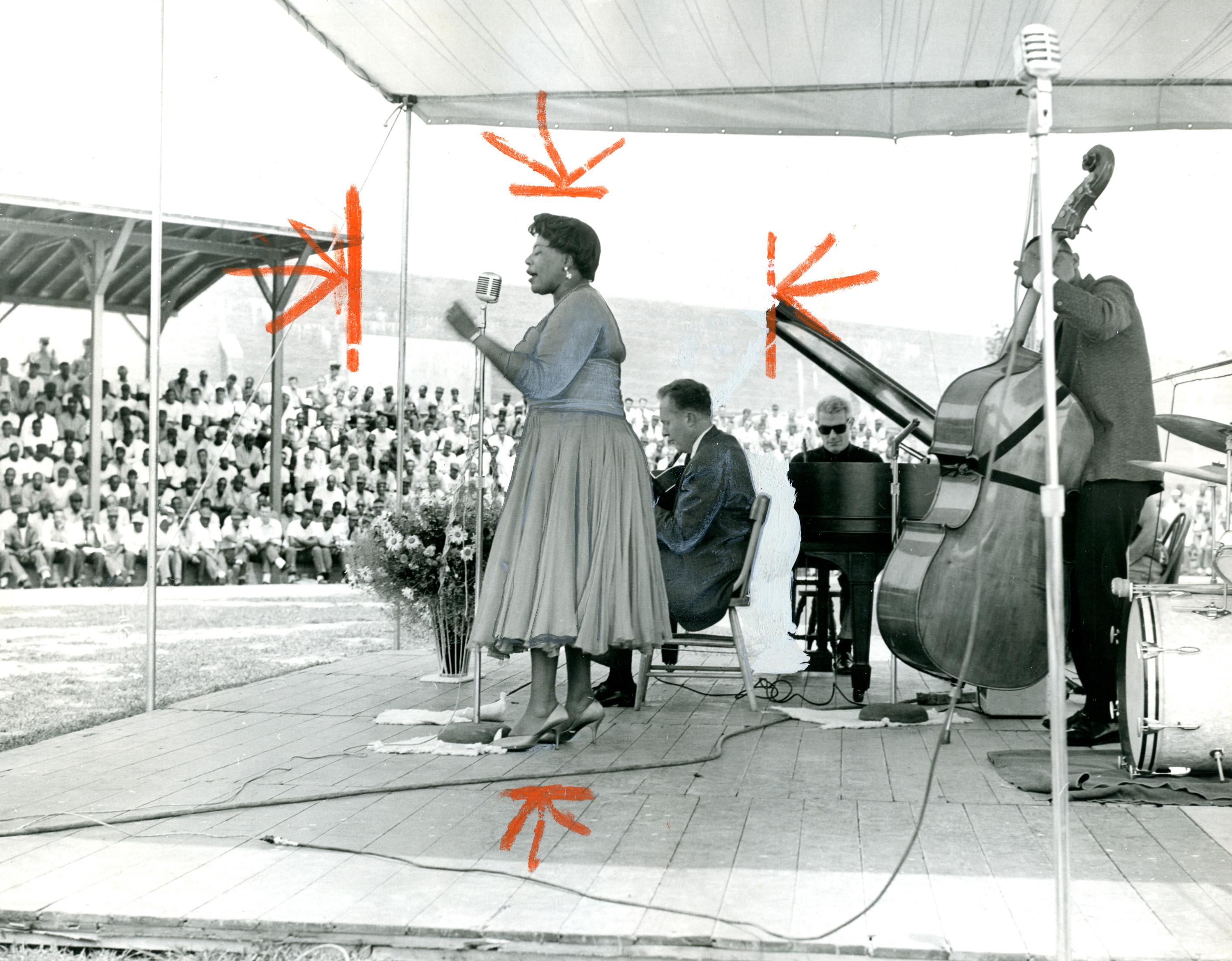

And a 1….a 2...a 1,2,3,4! Bam! The trumpets blared their first few crisp notes front and center introducing the snappy melody to the audience. The jazz band filled with trombones, saxophones, drums, and an upright piano created a swinging sound with surprising chord progressions and syncopation. The crowd of almost 2,000 shook and danced in their seats, tapping their feet and snapping their fingers until a woman stepped out from behind the band and into view. Ella Fitzgerald had arrived!

Smiling as she walked up to the microphone, it was clear that this wouldn’t be an ordinary performance. For one thing, the stage wasn’t in a luxurious music hall or a smokey jazz club filled with elegant ladies in evening gowns and intimate mood lighting. No, Ella Fitzgerald was standing, under the scorching rays of Virginia’s summer sun, on a mound of red dirt in front of home plate on the Lorton Reformatory’s baseball field. Her enthusiastic audience was composed of inmates that had been waiting all year to hear jazz music from the legends themselves.

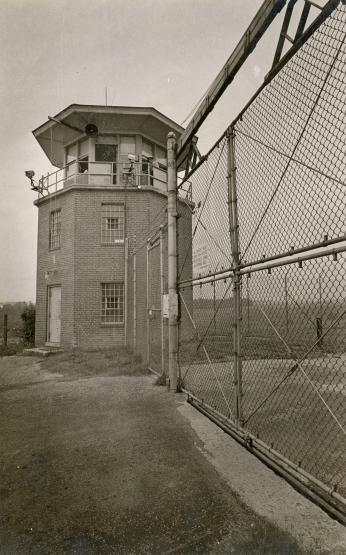

The Lorton Workhouse Reformatory and Penitentiary, located along the Occoquan River, was created as an alternative to D.C.’s overcrowded prisons. Opened in 1910 as an agricultural work camp, men imprisoned in Lorton were responsible for cultivating fields, caring for farm animals, and constructing surrounding buildings, while the women housed at the Woman’s Workhouse, opened in 1912, cooked and cleaned for both camps.[1] Over time however, the prison came to be defined by the disorganization and overcrowding it once sought to avoid. By the winter of 1955, Lorton Reformatory’s male inmate population was “some 500 above safe operations” according to a report from the D.C. Department of Corrections. Six months later, that number was 725 and, as the decades passed, the overcrowding intensified.[2] What was once promoted to be a self-sustaining rehabilitation program turned into a decaying and dangerous penitentiary that reflected nationwide larger struggles with correctional facilities.

Integral in caring and advocating for the inmates were two Catholic chaplains, Father Carl J. Breitfeller and Father Donald Sheehy. As Dominican priests, both men had taken vows of poverty and committed their lives to meeting the needs for the inmates, whether that meant taking law classes or learning about jazz music. In 1955, Father Brietfeller got a request from the inmates to visit jazz singer Sarah Vaughn during her Washington tour and ask for photos and autographs to bring back to the prison. Much to everyone’s surprise, Sarah Vaughn not only agreed to sign the pictures, but decided to visit the Reformatory with her band and play a free concert for the prisoners.[3] Inspired by the inmates’ joyful response after the performance, the Catholic chaplains decided to produce and direct another jazz show.

As Father Breitfeller recalled a few years later, putting on jazz concerts didn’t come naturally at first, but he was a quick study. “I didn't know a thing about jazz then. But I got interested because a lot of my boys were interested, and out of that grew our summer festival.”[4] That summer festival became an annual event known as the Lorton Jazz Festival, which attracted some of the jazz world’s biggest stars for an exclusive show before an audience of inmates.

Each year, months before the event, the inmates prepared for the festival by building a makeshift stage on the athletic fields and organizing the dugout to serve as a dressing room and storage area for musical equipment. As one inmate put it, “The day one festival is over we start thinking about the next. Ninety per cent of us are jazz fans and this is the biggest day of the year for us.”[5]

Meanwhile, the chaplains enticed local radio hosts like WMAL’s Felix Grant to emcee the event, and began the process of booking musicians.[6] Far from the organs and choirs of the churches he was used to frequenting, Father Breitfeller spent his nights pub crawling in an effort to line-up acts for the Festival. He described his process to reporters saying, “I’ve visited as many as three nightclubs in an evening. I go in, get to talking to the musicians, so they know me, and then when I need them they know what I want and are willing to help.”[7]

However, when one of the prisoners requested a performance from the great Ella Fitzgerald, the pressure was on. In the summer of 1959, Breitfeller prayed for a miracle as he approached Ella Fitzgerald after one of her shows in D.C. Despite his ball of nerves and pounding heart, he remembered quite simply that, “I went to see Miss Fitzgerald, got the autographs, and her promise to come sing for the prisoners.”[8]

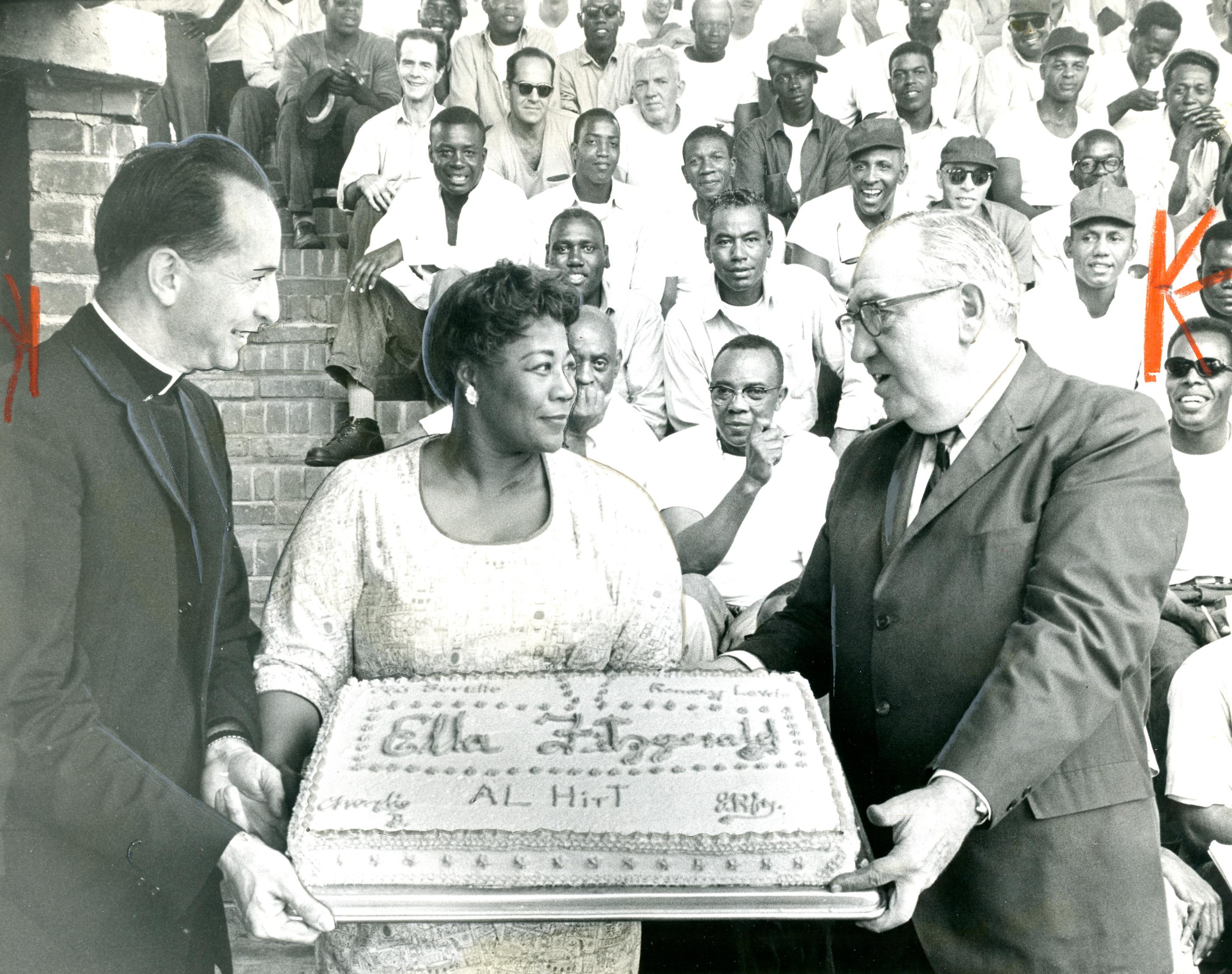

True to her word, Ella showed up to the Lorton Reformatory, along with legends Charlie Byrd and Oscar Peterson, and performed a virtuosic performance on the workhouse’s baseball diamond. The prisoners swayed to the rhythm in the stands during her two-hour blues set and hollered as she blew kisses to them upon leaving their homemade stage.[9] If you were lucky enough to sit directly behind home plate, you might have even gotten a wink from Ella herself. One convict remembered calling out “I love you, Ella!” only to be knocked off his feet when she responded, “Why, I love you, too!”[10]

Just when the prisoners thought booking Ella for their invitation-only jazz festival was the cherry on top of the cake, they were more than surprised to hear about who the chaplains had booked for the 1960 Festival. Listed on the program in big letters was none other than Count Basie and Louis Armstrong![11] Almost every inmate, over 1,900 to be exact, gathered in the stands to attend what was becoming the Washington area’s premier and most exclusive jazz concert, described in the Evening Star as “the talk of both the prison and music worlds.”[12]

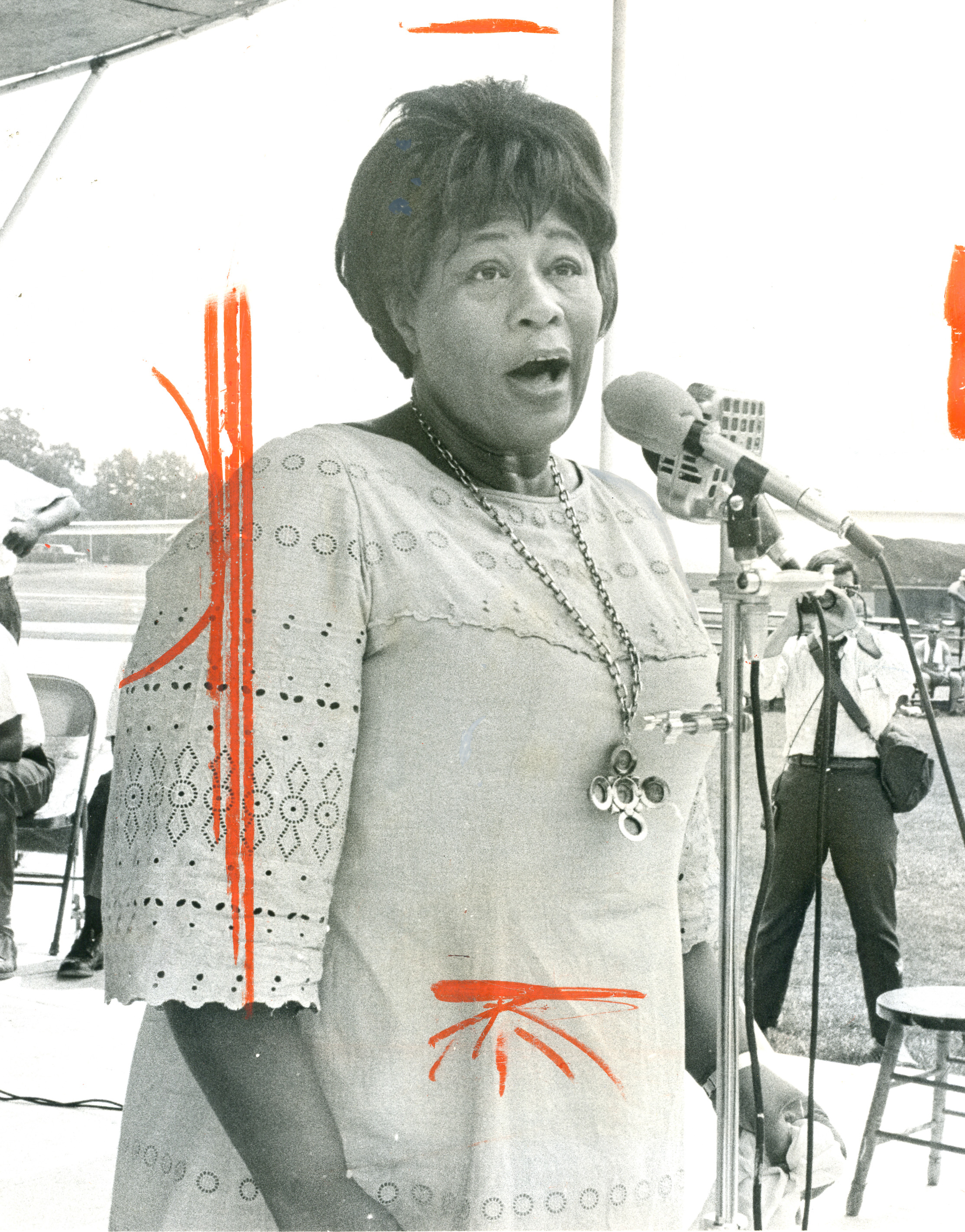

Year after year, the festival was a hit. Performing completely for free, the jazz superstars were paid in applause and gratitude by the prisoners. Ella Fitzgerald headlined the festival again in 1961 and 1963, joined by musicians including pianist Tommy Flanagan, saxophonist Stan Getz, and the J.F.K Quintet.[13] For the Festival’s 10th anniversary in 1965, the chaplains made history by naming not only Ella Fitzgerald but also Count Basie and Frank Sinatra as the headliners. It was the first time ever that the three legends would appear together on the same program...which was almost as exciting as the rumor that Frank Sinatra would make his entrance to the show via helicopter![14]

On the morning of the big performance, inmates went through their morning of roll-call and work detail as if it were any typical day. It was only when the sound of a bugle pierced through the workhouse that the inmates, clad in blue denim, rushed to the ballfield in time to see Sinatra step out of a Cadillac in a spiffy green sports coat.[15] For this performance, the legends were joined by the inmates on stage who formed the Lorton Reformatory’s own ten-man jazz band that serenaded the crowd between sets.[16] After unforgettable solo performances by Fitzgerald and Basie, Frank Sinatra made his way to the stand, gave the signal to the band, and began to entertain. “Sing it, Frankie, sing it!” one woman screamed as Sinatra sang classics like “I Wish You Love” and “Street of Dreams” for almost an hour.[17]

While no subsequent program could match the star power of 1965, the Lorton Jazz Festival continued to be a pillar of jazz entertainment at the prison and within the D.C. music scene for the next several years. In 1966, Ray Charles, adjusted his touring schedule to fly to Washington for the event which the New York Amsterdam News described as “one of the most stirring and enthusiastically received in Lorton’s history.”[18] For the last reported Festival in 1968, crowd favorite Ella Fitzgerald returned to the Reformatory once again. Her singing touched the hearts of all those in attendance. As the Evening Star’s John Sherwood remarked, “Everyone was smiling [because] Ella was talking to them, the way only Ella can.”[19]

Sherwood’s synopsis underscores the uniqueness of the Lorton Festival and what it meant to those involved. Despite the joy and celebration surrounding the performances, neither the inmates or the stars themselves could forget that they were still in a prison. Prisoners from the Reformatory, the women’s workhouse, and the youth center were shown to their seats by armed guards as opposed to ushers. Instead of spotlights, the musicians played under the surveillance of guards atop watch towers.

In that tense environment, the music provided an escape, but also something more. Beyond the obvious prison backdrop, performers recognized something different about the response they received at Lorton. As Father Breitfeller recounted, “They all [said] they would rather play for our people than for any other audience — that they seem to appreciate their music more.”[20]

For some, like inmate Lloyd Cooper, who played trumpet in the Reformatory’s jazz band and assisted with setup for the annual Festival, the concerts fed dreams to “start up a little four-piece group of my own” upon his release.[21] For others, the Festival’s impact was more difficult to put into words but no less meaningful. Perhaps Father Breitfeller put it best, “Jazz is a definite art form and an aid to rehabilitation...it is a reminder to the inmate that he is a human being.”[22]

Footnotes

- ^ “History of the Workhouse Arts Center,” Workhouse Arts Center.

- ^ “Eve Edstrom, “Justice Report Cites Dire Need of New Prison,” The Washington Post, July 1, 1956.

- ^ "Ella Fitzgerald Heads Lorton Jazz Fete,” The Washington Post, July 26, 1963.

- ^ Jim Birchfield, “Their ‘Parish’ Is Behind Prison Bars,” The Evening Star, July 3, 1960.

- ^ Asher, “1900 Inmates Cut Loose At Lorton Jazz Festival,” The Washington Post, August 12, 1960.

- ^ “D.C. Jail Skeds Blowout, But of Jazz Variety,” Variety, August 10, 1960.

- ^ Birchfield, “Their ‘Parish’ Is Behind Prison Bars.” The Evening Star, July 3, 1960.

- ^ Birchfield.

- ^ “Ella Fitzgerald Wows Captive Audience,” The Evening Star, June 26, 1959.

- ^ David Braaten, “Nobody Walks Out: Lorton’s Jazz Fete Is a Hit,” The Evening Star, July 26, 1963.

- ^ “Basie, Armstrong To Perform for Lorton Inmates,” The Evening Star, July 29, 1960.

- ^ Robert L. Asher, “1900 Inmates Cut Loose At Lorton Jazz Festival,” The Washington Post, August 12, 1960.

- ^ Braaten, “Nobody Walks Out: Lorton’s Jazz Fete Is a Hit,” The Evening Star, July 26, 1963.

- ^ “Only Invited May Watch Jazz Show,” The Washington Post, July 10, 1965.

- ^ Leroy F. Aarons, “Stars Visit Prison — and It’s a Riot,” The Washington Post, July 16, 1965.

- ^ “Only Invited May Watch Jazz Show,” The Washington Post, July 10, 1965.

- ^ Aarons, “Stars Visit Prison — and It’s a Riot,” The Washington Post, July 16, 1965.

- ^ “Ray Charles Headlined Prison Jazz Festival,” New York Amsterdam News, August 13, 1966.

- ^ John Sherwood, “Ella Sends Temperatures Soaring,” The Evening Star, July 18, 1968.

- ^ Birchfield, “Their ‘Parish’ Is Behind Prison Bars,” The Evening Star, July 3, 1960.

- ^ “Lorton: Inmates’ 1st Trumpet Plans Career Outside,” The Evening Star, July 27, 1966.

- ^ Asher, “1900 Inmates Cut Loose At Lorton Jazz Festival,” The Washington Post, August 12, 1960.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)