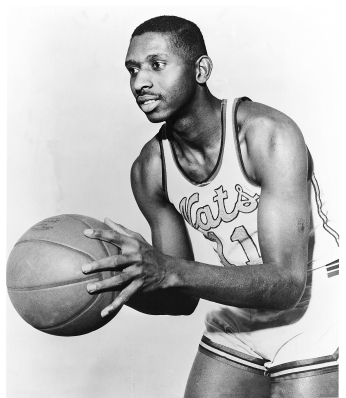

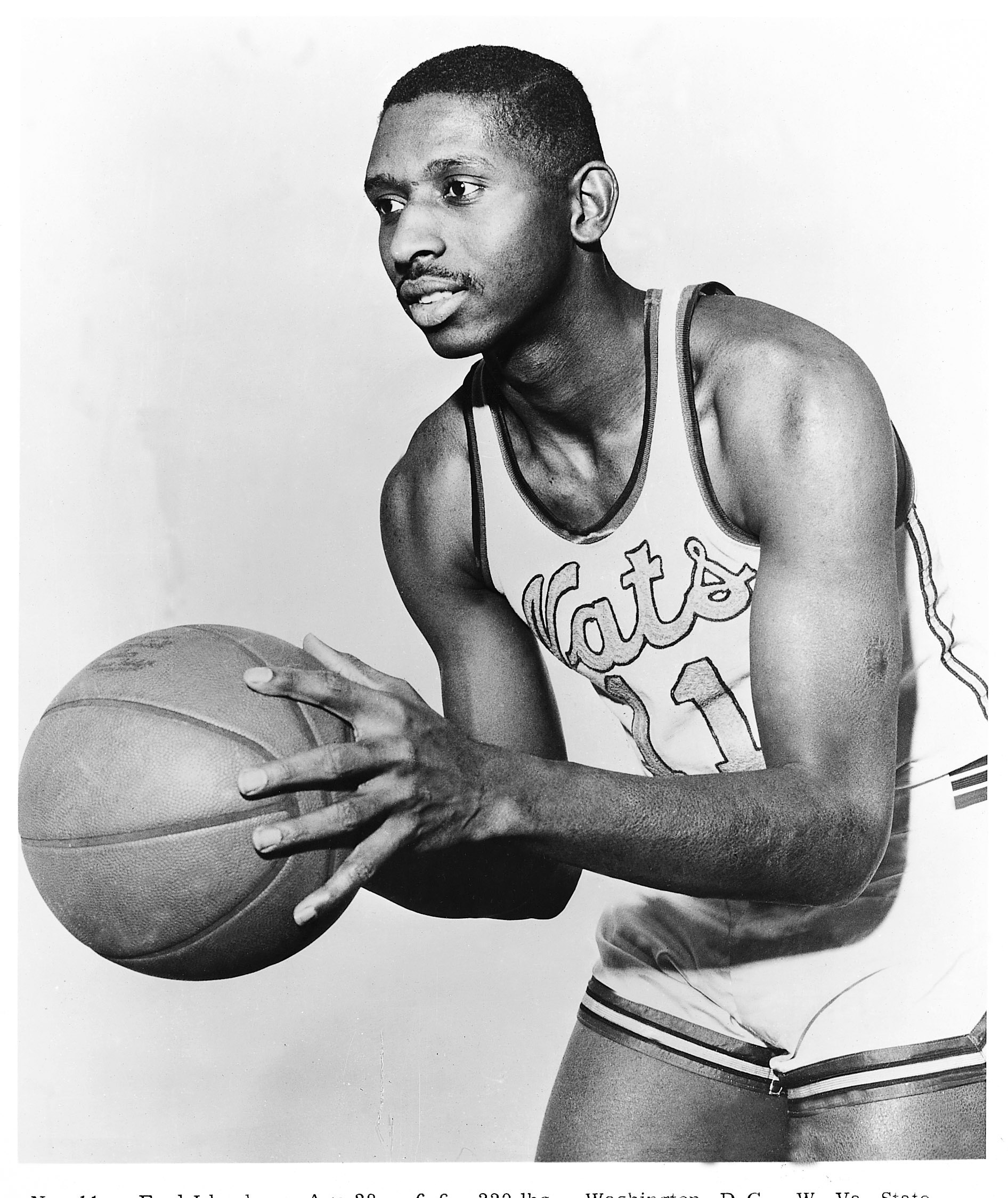

Alexandria's Earl Lloyd Breaks Basketball's Color Line

Earl Lloyd was a rising basketball star at West Virginia State College, but little did he know how soon he would become an important part of sports history. Toward the end of Lloyd’s senior season he was heading to class with a classmate and she told him she heard his name on the radio that day. Unaware of what she was referring to, Lloyd simply asked what she heard. She told him some team in Washington called the Washington Capitols had drafted him.

“You’re going to Washington and they’re going to try you guys out, so show them your best,” said Lloyd’s college coach, Marquis Caldwell.[1] Being from Alexandria, Virginia, it was almost a homecoming party for Earl Lloyd. Before he was at West Virginia State, he graduated from Parker-Gray High School in 1946, Alexandria’s only African-American high school.

Now defunct, the Washington Capitols team was a charter member of the Basketball Association of America, a forerunner to the National Basketball Association. Home games were played at Uline Arena, located at 1146 3rd Street, Northeast, Washington D.C. with a capacity of 7,500.

Under coach Red Auerbach, the Capitols won division titles in 1947 and in 1949. The next year, Auerbach left to became the head coach of the Boston Celtics. (Ironically both teams wore green and white uniforms.)[2] When Early Lloyd came to training camp in the fall of 1950, the Capitols were led by player-coach, Bones Mckinney.

For Lloyd, growing up in Jim Crow Alexandria, Virginia was not an easy task. “Integration had not taken place as you know and segregation was the order of the day and there’s nothing subtle about segregation, it was a nasty thing,” said Lloyd in an interview years later.[1]

Despite the challenges, Lloyd would find that his playground basketball experiences prepared him well for the Capitols. “The playground basketball wars in D.C. made college and the NBA a piece of cake.”[3]

Hal Hunter, an African American player from North Carolina College who Lloyd had battled in college, was included in the tryout along with Lloyd, but his height and position hindered him making the team.

During the early days of the NBA, teams were composed of white athletes. “I played against Hal for four years, Hal was a great player but during that time when the first black guys came in the NBA they weren’t taking any small guys…back court people,” said Lloyd. “Because the thing was like in pro football black guys couldn’t be quarterbacks because they weren’t ‘smart enough,’ they said and in basketball they also said black point guards couldn’t run a pro basketball team.”[1]

The year Lloyd was drafted; two other black players were drafted before him. Chuck Cooper of the Celtics, and Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton, of the Knicks—were both selected in the 2nd round, Lloyd in the 9th. However, a scheduling quirk meant that Lloyd was the one who made history. The Capitols opened their season on October 31, one day before Chuck Cooper’s first game and four days before Clifton’s.

Lloyd’s debut was against the Rochester Royals in Rochester, New York. On the night of the game, after the announcer read the lineup a white man in the front row said, “Do you think that nigger can play any basketball?” Lloyd’s mother told him not to worry, “that ‘nigger’ can play.”[4]

Although the Capitols lost 78-70, Lloyd’s impact was felt as he finished with a respectable six points.[5] He reflected on the history-making night saying, “Rochester, New York…cold weather, most people told me about that the Ku Klux Klan is going to be there with ropes and all of that kind of stuff you know…. If you had to handpick a town to play a game with all of that controversy, they picked the right place…it would get so cold in the winter that no one hates anyone.”[1]

The next night, Lloyd and Capitols returned to Washington to take on the Indianapolis Olympics at Uline Arena. As it turned out, he would only play a total of seven games with his hometown team, as he was drafted into the Army for the Korean War. By the time he returned to basketball the following season, the Capitols had folded due to bad finances.

Lloyd joined the Syracuse Nationals and became a key component in their 1955 championship run, before finishing his career with the Detroit Pistons.[6]

As important as Lloyd’s integration was he downplays it, “People try to compare me to Jackie Robinson, but I don’t know about that,” Lloyd said. “He was one of my heroes. There was totally a different attitude in basketball than baseball. It was going to be somebody sooner or later.”[6]

Maybe so, but that somebody was Alexandria, Virginia’s Earl Lloyd.

Footnotes

- a, b, c, d Mike Ortiz Jr. “The Journey Earl Lloyd: The First Ever African-American Player Speaks”. Bleacherreport.com. May 1 2011.

- ^ Dick Welss. “West Virginia State to Reveal a Statue to Honor Earl Lloyd”. Coachgeorgeraveling.com

- ^ Dave Wieme. “Earl Lloyd Making a Difference: Profiles in Black History”. nba.com.

- ^ “October 31 1950: Earl Lloyd Becomes first black player in the NBA” history.com

- ^ Washington Capitols at Rochester Royals Box Score, October 31, 1950. Basketball-reference.com.

- a, b Paul Corliss. “Earl Lloyd: A True Hardwood Pioneer”. Feb. 1 2012. Legendsofbasketball.com

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)