Mrs. Woodhull Goes to Washington: The First Female Presidential Candidate Petitions For Women's Suffrage

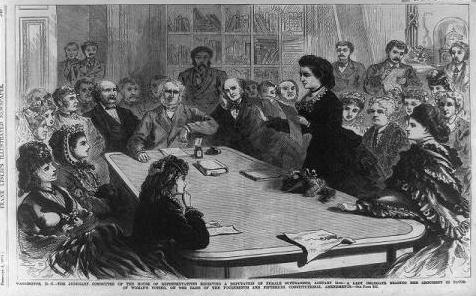

Victoria Woodhull was already planning her presidential run when she made her landmark address to the House Judiciary Committee on January 11, 1871. In her speech, she argued that women, as citizens, should already have the right to vote, becoming the first woman to address a Congressional committee in the process. Outspoken and liberal even by today’s standards, by this time Woodhull had already had a list of “firsts” under her belt. Along with her sister, the two were the first female stockbrokers[1] and the first women to own and run their own newspaper, Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly.[2] Woodhull was also a nationally recognized figure in the suffragist movement, and for a time was as prominent as Susan B. Anthony; she used this recognition to run for president in 1872, becoming — once again — the first woman to do so. Her fiery entrance onto the national political stage, however, happened right here in Washington, DC.

Although Woodhull lived and practiced in New York, she made her way to DC in 1871 for the National Woman’s Suffrage Convention (NWSC), as well as the event that gained her some measure of recognition among the suffragist community. Woodhull led a group of suffragists, including Susan B. Anthony and Isabella Beecher Hooker, in addressing the House Judiciary Committee on the subject of women’s suffrage.[3] Woodhull did not argue that women should be granted suffrage — she declared that they already had it, based on the 14th (sometimes misreported as the 15th) Amendment to the Constitution, which stated that no citizen could be denied suffrage “based on race, creed, or color,” and that “no State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.” This last clause, in the minds of the NWSC, proved that the states were denying women, as citizens, their right to vote.

In her January 2 petition submitted to the Judiciary Committee, Woodhull struck out at the institution that would not let her and her compatriots vote:

“‘No taxation without representation’ is a right that was fundamentally established at the very birth of our country’s independence; by what ethics does any free government impose taxes on women without giving them a voice upon the subject or a participation in the public declaration as to how and by whom these taxes shall be applied for common public use?”

When she went on to deliver her argument to the Judiciary Committee nine days later, on January 11, many around the country took notice, with newspapers ranging from the Washington Evening Star to the Owyhee Avalanche in Idaho printing small pieces on Woodhull’s petition. It was covered mostly as a curiosity, with the press tending to focus on the women’s outfits or their suffragette status rather than the actual substance of their speeches. As the Philadelphia Inquirer put it, the House Judiciary Committee was gathered “to listen to Miss Victoria C. Woodhull’s brilliant argument, based upon the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. Mrs. Woodhull is of very prepossessing appearance, with light brown hair, worn short. She was dressed in navy blue cloth, trimmed with black gros grain, and made with postillion basque; very high crowned broad-rimmed black felt hat, with velvet band around the crown completed the unique costume of the Wall street brokeress.”[4] The majority of the article follows in this vein; this is almost the only sentence in the article to address the substance of the women’s speeches.

Through the layer of sexism that you’d pretty much expect from the 1870s, however, the reporters had to concede the power and cogency of Woodhull’s arguments. The New York Herald reported, in their article “A Delegation of Fair Ones Before the House Judiciary Committee,” that “[Woodhull] had presented the case in as good style as any Congressman could have done,” marveling that “[h]er voice was very clear and she did not appear to be embarrassed in the least[.]”[5]

The argument, although apparently well-delivered, failed to convince the committee, and all but two of them voted to table Woodhull’s proposal. As the New York Herald declared: “The advocates of woman suffrage, who have been on the rampage in Washington ... were checked in their wild career yesterday.”[6] Other papers were not so hyperbolic, but the general sentiment was the same: the NWSC’s were ridiculous claims. The Judiciary Committee released a report on January 30, declaring

“The limitations specified in the fifteenth amendment exclude the conclusion that a State of this Union, having a government republican in form, may not prescribe conditions upon which alone citizens may vote other than those prohibited. It can hardly be said that a State law which excludes from voting woman citizens, minor citizens, and non-resident citizens of the United States, on account of sex, minority, or domicile, is a denial of the right to vote on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

Woodhull tried to follow up by addressing the House of Representatives as a whole on behalf of suffrage, but her request to speak on the floor was denied.[7]

Although she may not have convinced the House or the majority of the press, Woodhull’s speech did convince the suffragist community that she was a serious political contender, leading to her nomination by the Equal Rights Party as their candidate for president in the 1872 election. Her platform included government jobs for the unemployed, a graduated income tax, public referendums on laws passed by Congress, and equal rights for women.[8] The rest of her campaign was as colorful as the woman herself. Among the highlights is the fact that Frederick Douglass was nominated as her running mate without his presence, knowledge, or consent. Douglass ignored the Equal Rights Party’s nomination and eventually publicly supported one of Woodhull’s opponents, incumbent Ulysses S. Grant.[9] Woodhull became notorious in the popular press as “The Woodhull,” as they vilified her over the course of her campaign, accusing her of blackmail and sexual immorality, and making out her home life to be a soap opera-like parade of infidelity, marital power games, and even murder.[10]She was even caricatured in DC’s Carnival parade, with a squadron of female soldiers and a brass band, putting her on a throne as “The Female President."[11]

Woodhull, of course, could not vote for herself in the election, but neither could her husband, since the two of them, along with her sister, were arrested on obscenity charges three days before the election for printing an exposé on Henry Ward Beecher’s (a preacher who was one of her main detractors) adultery and affairs.[12][13] Woodhull did not end up winning any electoral votes — she was also a year too young to legally hold the office — but she paved the way for the three dozen subsequent female candidates[14] that have run for the highest office in America.

More on the proposal

The Judiciary Committee’s response: http://www.federalistblog.us/h-r-report-no-22-bingham/

More on Victoria Woodhull

Her presidential run: http://www.victoria-woodhull.com/whoisvw.htm

Excerpts from her newspaper: http://www.victoria-woodhull.com/wc050400.htm

Footnotes

- ^ The pair were backed by Cornelius Vanderbilt and were wildly successful.

- ^ Woodhull was a woman of many vocations. It is often reported that she was also a prostitute, but these rumors are unsubstantiated – they’re based solely off of her characterization in the newspapers of the time, a caricature of her ideals of free love.

- ^ Hartford Daily Courant, January 12, 1871.

- ^ Philadelphia Inquirer, January 14, 1871. This article was at the bottom of the society column entitled “RECEPTIONS AT THE CAPITAL,” detailing parties thrown and outfits worn by wives of politicians, which is generally indicative of the overall tone of the article.

- ^ New York Herald, January 12, 1871. The article is subtitled “Grand Display of Ancient and Tender Loveliness,” a vaguely creepy way to describe a committee meeting.

- ^ New York Herald, January 14, 1871. Another choice quote: “Mr. Loughridge, of Iowa, a man who would hardly be suspected of such a weakness, presented his report...in support of the claim of woman suffrage”

- ^ Evening Star (Washington, DC), February 15, 1871.

- ^ New York Herald, May 11, 1872.

- ^ The New Northwest (Portland, OR), July 5, 1872.

- ^ Evening Star (Washington, DC), February 15, 1871; New York Herald, June 8, 1871. Check out the latter if you’re interested in the aforementioned soap opera.

- ^ Evening Star (Washington, DC), February 22, 1871.

- ^ Her husband, by the way, is referred to only as “Col. Blood” in most documents and newspapers, which makes him sound like an old-timey supervillain. This also means that Woodhull passed up the opportunity to be called Victoria Blood, which, to me, is the greatest tragedy of her campaign.

- ^ New York Herald, November 5, 1872, pg. 4.

- ^ Women who have obtained a political party’s nomination, not including Vice Presidential candidates Geraldine Ferraro and Sarah Palin, or the numerous other women who have run for a party’s nomination and lost.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)