Chaos and Persistence at the 1913 Women's Suffrage March

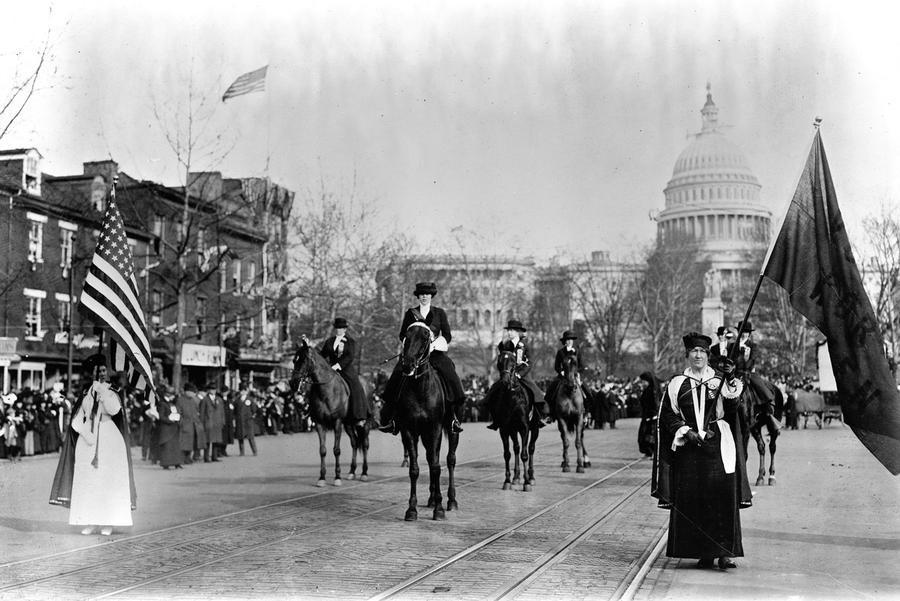

The 1913 Women's Suffrage Parade marches down Pennsylvania Avenue, in view of the Capitol Building (Credit: Library of Congress)

In 1912, the women’s suffrage movement, founded almost 60 years before by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, had reached a stalemate. The largest suffrage association, the National American Woman Suffrage Association, or NAWSA, was working at a state level: traveling state to state and lobbying for changes to state constitutions. Six Western states had granted female suffrage before 1912, and five states would grant women's suffrage in 1912 and 1913.[1] However, the debate over women’s suffrage had yet to reach the House of Representatives, and repeated petitions presented in Washington by delegations of suffragettes had achieved no action. [2]

Enter Alice Paul, a well-educated young woman from New Jersey with Quaker roots. While fighting for the vote in England, Paul had been repeatedly arrested, imprisoned, taken part in hunger strikes and had been forcibly fed. It was in England too that she became acquainted with Lucy Burns, a New Yorker and future ally, as both were participating in the active, radical British suffrage movement. When the pair arrived at the 1912 national convention of the National American Woman Suffrage Association in Philadelphia, they proposed radical new ideas for the American movement, including efforts to pass an amendment to the United States Constitution permitting women’s suffrage. The pair encountered some resistance from the more conservative members of NAWSA, who agreed with Paul’s parade proposal only after she promised to raise the necessary funds through her own efforts. NAWSA also gave Paul the head of leadership at the Congressional Committee in Washington, though she soon discovered that the branch had no headquarters and very few members.

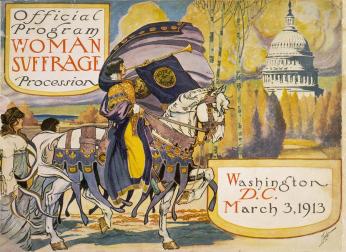

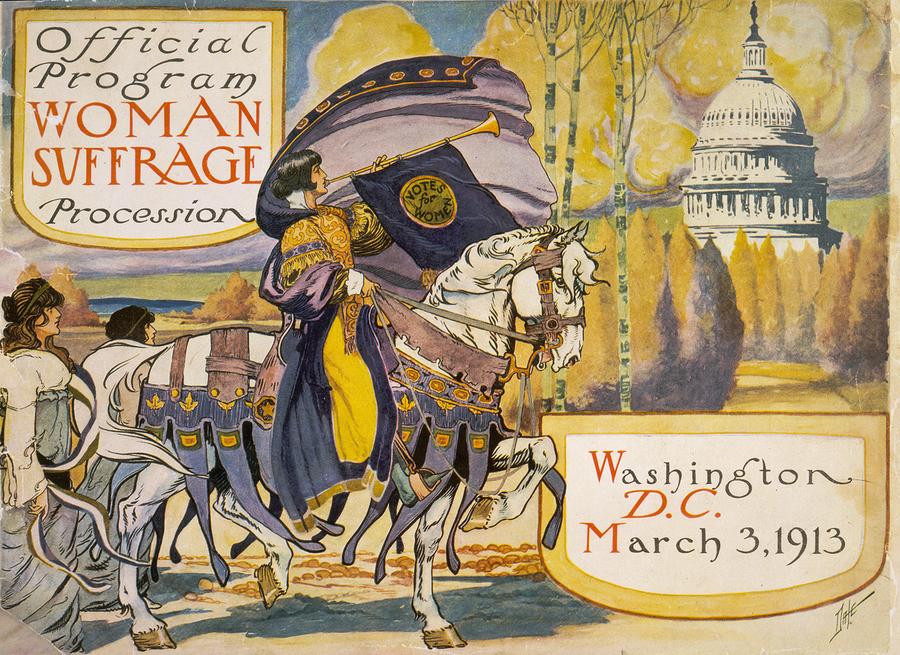

Alice Paul took control of this Congressional Committee beginning in December 1912, and soon began planning for a parade to coincide with the upcoming inauguration of President-elect Woodrow Wilson in March 1913.[3] The parade was meant to model similar suffrage pageants that had been held in Britain and the local marches in New York held by the radical Women’s Political Union.[4] Calls were put out in leaflets and broadsides calling suffragettes from all across the country, and the call was answered. The most dramatic trip to the march was the journey of 16 “suffrage pilgrims” who left New York on February 12, 1913 and walked down to Washington to arrive just in time for the parade. Another New York suffragette, Elizabeth Freeman, traveled to Washington dressed in gypsy attire and riding in a yellow, horse-drawn wagon decorated with suffrage symbols.[5]

On March 3, 1913, the day before the inauguration of President Wilson, 5,000 women marched on Pennsylvania Avenue to demand their right to vote. In the program for the event, the women emphasized the righteousness of their cause and the reason for which they chose to march. “We march in a spirit of protest against the present political organization of society, from which women are excluded.”[6] The parade traveled from the Peace Monument to the Treasury Building, then to a rally at Continental Hall in support of women’s suffrage.

Wilson arrived in Washington on the day of the parade to find very few people present to greet him at the train station. When a member of his staff asked why so few people were present, the reply came from the police. All of the crowds which Wilson had expected were instead “Watching the suffrage parade.”[7]

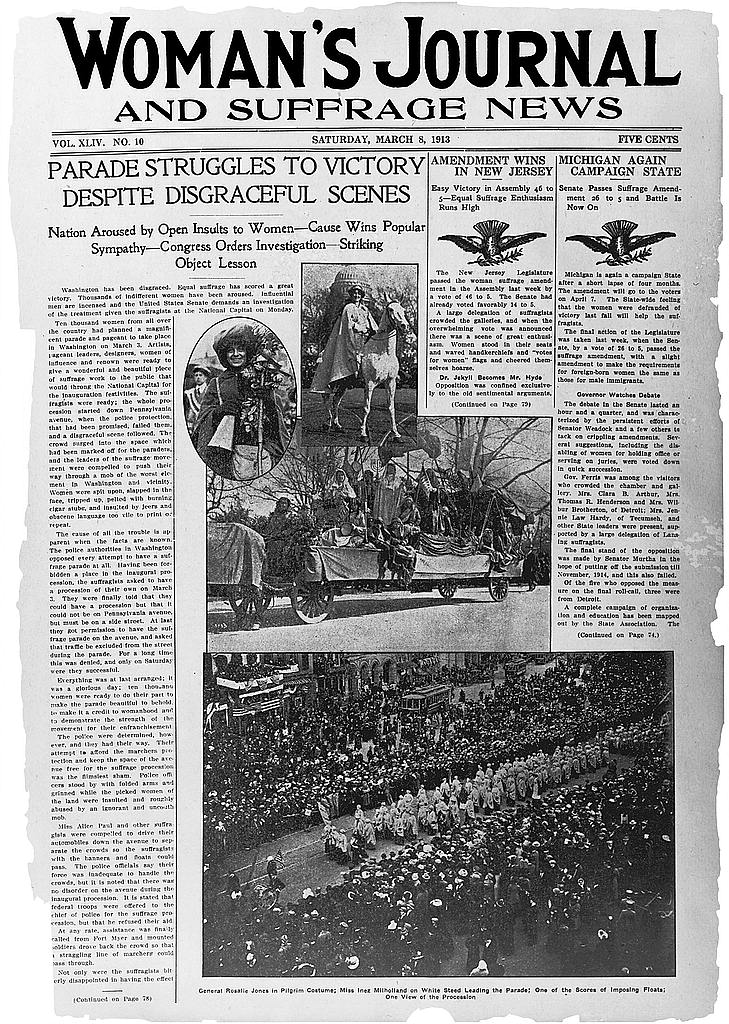

Spectacle and stagecraft were utilized by the marchers to draw attention to their cause. Riding on a white horse was attorney Inez Milholland, who wore a large cape and cut a striking figure that became emblematic of the 1913 march. Milholland, born a New York aristocrat, would die in 1916 at age 30 after collapsing onstage at a suffrage event in Los Angeles.[8]

The women marched in groups while wearing brightly colored uniforms depicting different occupations held by women, including farmwomen, homemakers, educators, clergywomen, workers, businesswomen, writers, musicians, lawyers, doctors, actresses, social workers and librarians. Extravagant floats depicted the progress of suffrage in the United States over the previous seventy years and accompanied delegations from many states and foreign countries.[9] At the end of the route, the marchers created a series of tableaux on the steps of the Treasury Building, featuring actresses and performers acting out the roles of Columbia, Justice, Liberty, Charity, Plenty, Peace and Hope.[10]

What started off as a peaceful scene quickly devolved into violence. The parade encountered opposition in the streets as the crowd, many of the men gathered for the inauguration of the new President, became violent and disorderly. Police were either unwilling or unable to keep the crowds in line, and at times along the route, the march descended into chaos, with members of the crowd attacking the suffragettes and frantic scuffles taking place in the street. By the end of the day, over 100 marchers had been hospitalized.[11] An article from The New York Times focused on the march described how the march began in glorious sunshine and then descended into mass chaos at the rush of the unruly crowds.

In every side street near the Capitol were organizations waiting to fall in line. Weather conditions were ideal. The sun shone brightly and it was just cold enough to make walking enjoyable. The waiting paraders took up the march with zest. It was when the head of the procession turned by the great Peace Monument and started down Pennsylvania Avenue that the first indication of trouble came. Hearing the bands strike up, the crowds on both sides of the avenue pushed into the roadway. At once the police authorities knew that they had not made proper plans for keeping the spectators in restraint. Looking down the avenue the paraders saw an almost solid mass of spectators. With the greatest difficulty the police were keeping open a narrow way. As far as the eye could see, Pennsylvania Avenue, from building line to building line, was packed. No such crowd had been seen there in sixteen years.[12]

One group of marchers was aided in their passage by the male students of the Maryland Agricultural College who had formed their honor guard.[13] A troop of Army cavalry called from Fort Myer helped to clear the route, and despite the harassment and violence, the march continued to its end.[14] Still, the agitation so disturbed Helen Keller that she was left “so exhausted and unnerved by her experience in attempting to reach a grand stand, where she was to have been a guest of honor that she was unable to speak later at Continental Hall.”[15]

While the marchers all came to Washington under the summons of Alice Paul, the suffrage parade and the national suffrage movement reflected the racial divisions which dominated in American society. White suffragettes, including Paul, made efforts to limit the participation of African American women in the march. Mary Church Terrell, one of the first African-American women to earn a college degree, had long struggled to participate in the national women’s suffrage movement. At a 1904 meeting of the National Woman’s Suffrage Association, Terrell had made a frank demand for an intersectional understanding of the suffrage question, saying “My sisters of the dominant race, stand up not only for the oppressed sex, but also for the oppressed race!”[16] Terrell would march in the parade with the sisters of the African American sorority Delta Sigma Theta, recently founded at Howard University.

Other black women who sought to participate in the march were told to march in a separate black delegation at the rear of the procession.[17] The Illinois delegation at the parade refused to allow Ida B. Wells, a noted journalist, suffragist, and anti-lynching advocate to join them in the parade, leaving her nearly in tears. In defiance of this order, Wells joined the Illinois group mid-parade, after the march had begun to encounter violent resistance in the streets.[18]

Front page of the "Woman's journal and suffrage news" with headlines discussing the violence at the march. (Credit: Library of Congress)

Ultimately, the chaos would gain the suffragettes sympathy from many quarters as many people grew disturbed by the violence of the anti-suffrage opposition. Congressional hearings would be held wherein the cause of the violence was investigated, with over 150 witnesses testifying about the events of that day. The superintendent of police of the District of Columbia would lose his job as a result of his conduct before and during the march.[19]

Following the 1913 March, Alice Paul and her allies would continue the use of radical tactics to agitate for women’s suffrage. Increasingly apart from the more conservative NAWSA, Paul and Burns would found the National Woman’s Party and engage in a picketing campaign at the White House. This picketing, even in the midst of the First World War, would earn the scorn of President Wilson as well as of fellow suffragettes, but the continued pressure of protests in the nation’s capital would help to cause a change in sentiment and in law.

The contributions of American women to the war effort, the persistent lobbying of the NWP and other groups, and the growing public support for women’s suffrage would contribute to a change of heart in Washington. President Wilson endorsed the 19th Amendment on January 9, 1918, and it passed the U.S. Senate in June 1919. On August 24, 1920, Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the 19th Amendment, and it was signed into law on August 26, 1920.[20]

The participants and organizers of modern protest marches can take heart in knowing that the suffrage parade did succeed in its goal of raising awareness to the cause of women’s suffrage, although it required sustained effort to transform the moment into a movement. The passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920 enfranchised American women following years of struggle for this right to civic representation. Despite this legislative success, the work was not yet done. Many states, especially those in the South, had enacted poll taxes, literacy tests, and other requirements designed to disenfranchise black voters of both genders. As a result of these measures, women of color did not have the same protections for their right to vote until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Footnotes

- ^ https://www.nationalgeographic.org/news/woman-suffrage/

- ^ http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/awhhtml/aw01e/aw01e.html

- ^ https://memory.loc.gov/ammem/awhhtml/aw01e/aw01e.html

- ^ https://www.loc.gov/collections/static/women-of-protest/images/history.pdf

- ^ http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/awhhtml/aw01e/aw01e.html

- ^ https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbpe.20801600/?sp=3

- ^ http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/awhhtml/aw01e/aw01e.html

- ^ https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/original-womens-march-washington-and-suffragists-who-paved-way-180961869/ https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/museums/100-years-after-suffrage-march-activists-walk-in-tradition-of-inez-milholland/2013/02/27/532872c0-7f7a-11e2-b99e-6baf4ebe42df_story.html?utm_term=.167dffeb6f35

- ^ https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/woman-suffrage/5000-women-march/

- ^ 5,000 of Fair Sex Ready to Parade. March 3, 1913. The Washington Post.

- ^ https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2013/03/100-years-ago-the-1913-womens-suffrage-parade/100465/

- ^ https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/woman-suffrage/5000-women-march/

- ^ https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/woman-suffrage/5000-women-march/

- ^ https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/the-day-the-deltas-marched-into-history/2013/03/01/eabbf130-811d-11e2-b99e-6baf4ebe42df_story.html?utm_term=.82ee76883e9f

- ^ https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/woman-suffrage/5000-women-march/

- ^ http://nationalwomansparty.org/womenwecelebrate/mary-church-terrell/

- ^ https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/original-womens-march-washington-and-suffragists-who-paved-way-180961869/

- ^ https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/the-day-the-deltas-marched-into-history/2013/03/01/eabbf130-811d-11e2-b99e-6baf4ebe42df_story.html?utm_term=.d2a82365607a

- ^ http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/awhhtml/aw01e/aw01e.html

- ^ https://www.loc.gov/collections/static/women-of-protest/images/history…

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)