A Place for the Poor: Resurrection City

In the early morning hours of June 23, 1968, thick clouds of tear gas rolled through a multitude of shacks on the National Mall. This shantytown was Resurrection City, and its residents were the nation’s poor. As many ran from their shelters, they saw Martin Luther King, Jr.’s final dream of economic equality withering in the gas. They had been citizens of the city for six weeks, all the while campaigning for rights for the poor around D.C. Now their work seemed all for naught. After an increase in violence and with an expiring living permit, the police had come to chase them out. Children were crying, adults screaming, and some were even vomiting. But amid the chaos, a song rang out: “we shall overcome.”

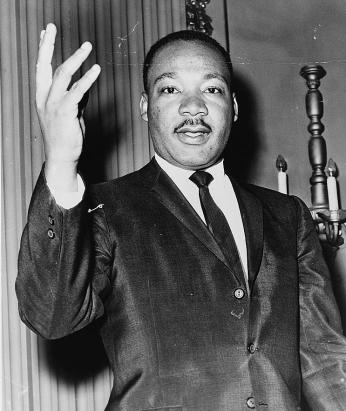

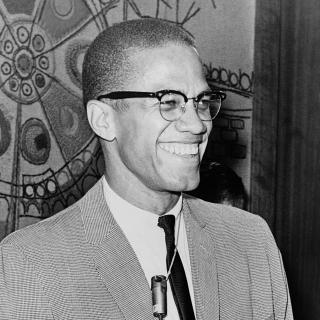

The idea of a movement for the poor was born in the fall of 1967 by King and other members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). It was officially announced as the Poor People’s Campaign in Atlanta on December 4.[1] After the success of the March on Washington and the passing of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts, the SCLC. decided it was time to extend equality to the millions impoverished across the country. While the movement intended to include people of all ethnicities, it was inherently tied to race and many saw it as a continuation of the Civil Rights Movement. A brochure for the campaign, entitled “Can America End Poverty?” blamed poor conditions on “racism and discrimination [that] cause families to be kept apart, men to become desperate, women to live in fear, and children to starve.”[2]

But above all, the Poor People’s Campaign sought to expand President Johnson’s 1964 War on Poverty into a broader national commitment that would improve the lives of everyone affected by scarcity. In January of 1968, King made a speech to rally support:

“We are tired of being on the bottom. We are tired of being exploited. We are tired of not being able to get adequate jobs. We are tired of not getting promotions after we get those jobs. And as a result of our being tired, we are going to Washington, D.C., the seat of our government, to engage in direct action for days and days, weeks and weeks, and months and months if necessary, in order to say to this nation that you must provide us with jobs or income.”[3]

With the encouragement of those inspired by King’s message, the SCLC drew up an Economic Bill of Rights in February. The document included five demands for all poor people: a meaningful job, a living wage, access to land, access to capital, and the ability to play a role in the government.[4] The plan was to take these claims to Congress in a new march on Washington. The keystone would be the construction of Resurrection City: an illustrative slum meant to open Washingtonians’ eyes to conditions of poverty in America. Protesters were to live there by night and picket by day.

All was set for the start of the Poor People’s Campaign in April of 1968. But with the assassination of King on April 4, everything changed. SCLC leaders, including King’s widow Coretta, debated whether or not the movement should still take place. It was eventually decided that while King had died, the need to fight against poverty had not. Reverend Ralph Abernathy, as new president of the SCLC, took over leadership and pushed back the start date to May 12.[5] It seemed like the right decision. Shortly before the demonstrators were to arrive in D.C., he was granted a temporary permit by the National Park Service for 3,000 people to set up camp in the grassy area to the south of the Reflecting Pool: the perfect location.[6]

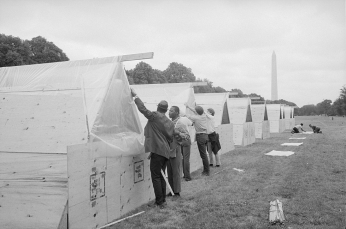

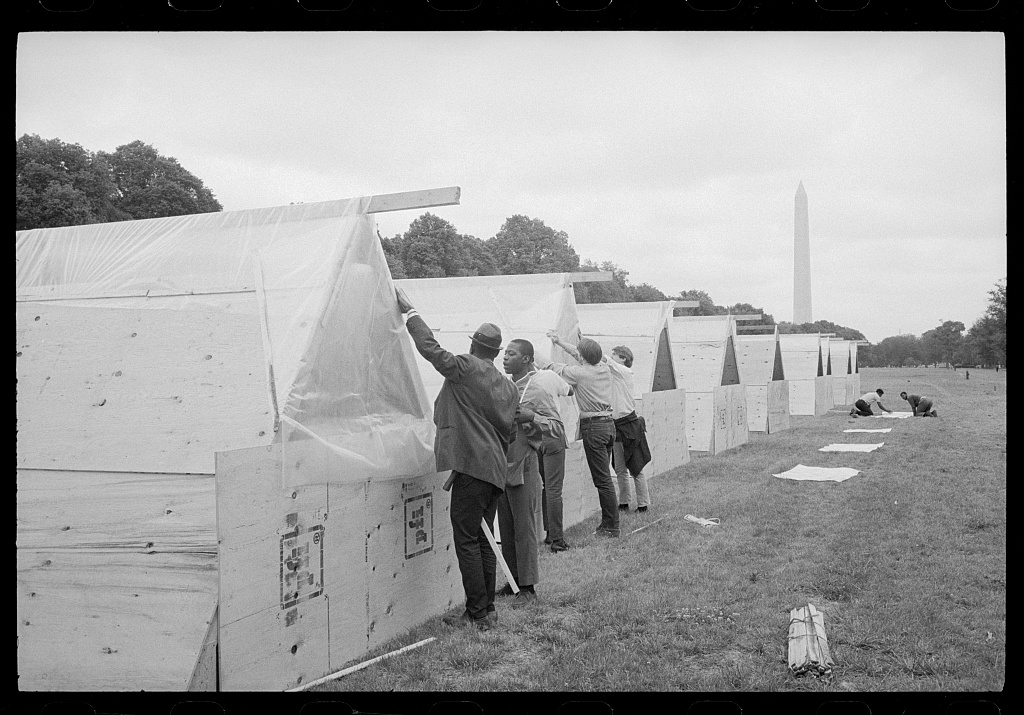

Within a few days, Abernathy drove the first stake of Resurrection City and construction officially started. Working off of a plan by architect John Wiebenson, SCLC members and workers from the Department of the Interior quickly began to erect more than 650 plywood and plastic-sheeting huts. Their city would have three dining facilities, a medical tent, a nursery, a city hall, and more. A small government was even constructed, to be led by “mayor” and SCLC member Jesse Jackson. This leadership contingent was in charge of organizing demonstrations and overseeing the management of the city’s “marshals” responsible for security.[7] But even with everything laid out, it takes more than a few days to construct a city. Before Resurrection City could open its doors, the starting day of the campaign arrived.

On May 12, 5,000 individuals flocked to D.C. for a Mother’s Day March, led by Coretta Scott King. The march hoped to jumpstart the movement by enlisting the support of “black women, white women, brown women, and red women – all the women of this nation – in the campaign of conscience” to end poverty.[8] It was a success. While many of the protesters came simply for the march, others decided to stay.

Local schools and churches stepped up to shelter the marchers until Resurrection City was in a livable condition. In the meantime, the nation’s poor continued to file in. The SCLC had recruited demonstrators from five southern states and ten major northern cities, and caravans were rolling in from Marks, Mississippi to New York City. The crowd was two-thirds African American, with the other third consisting primarily of whites.[9]

On May 15, although it was only about a third completed, Resurrection City welcomed this unique group. Many found it to be in better condition than the housing they normally inhabited. “Talk about poor,” photographer Jill Freedman remarked, “some of these people raised their whole standard of living just by moving in.”[10] But though the city had rudimentary plumbing and electricity that many were not accustomed to, it was crowded, hot and, above all, a muddy mess.

The summer of 1968 was a particularly rainy one. Only 14 of the 42 days Resurrection City stood were dry. As the city moved toward completion and its population kept climbing, health officials worried about the abundance of mud and soggy plywood homes. But the conditions did nothing to deter the residents’ hope. Demonstrations began on May 21 with picketers at the Capitol, the Departments of State and Agriculture, and other locations. Like its predecessors, the movement was to remain peaceful. “We’re going to raise hell downtown,” Abernathy told the protesters, “but we’ll have no violence.”[11]

Despite the nonviolent nature of their demonstrations, it seemed the Poor People’s Campaign had little luck. On May 23, a group was arrested outside the Capitol for lack of a protesting permit. Jackson negotiated with police to reduce the arrests, but 18 people were still charged.[12] Some good did come out of the incident, however. Interested by the mass of people outside their windows, a small group of congressmen created an ad hoc committee to improve communication with the campaign leaders. On June 5, 15 of them visited Resurrection City.

At this point, the makeshift city had taken on a character of its own. Shacks were decorated with slogans and graffiti, “funny and inspirational by turn, which illustrated the human need to put a personal stamp on even the most primitive and temporary of shelters.”[13] It buzzed with activity of all different kinds of people, and neighbors socialized and sang in the shadow of the city hall. Freedman, who lived in the city while photographing its residents, remarked how normal it was: “If you forget about things like traffic lights and dress shops and cops, Resurrection City was pretty much just another city. Crowded. Hungry. Dirty. Gossipy. Beautiful. It was the world, squeezed between flimsy snow fences and stinking of humanity.”[14] When they weren’t protesting, residents clustered together and talked about their home lives and what they hoped would come of the campaign. The city even had its own zip code: 20013.

The congressmen were moved by the life of the place from their visit. Head of the ad hoc committee Senator Edward W. Brooke promised the residents to hold hearings at the camp so they could convey their complaints directly to congressmen.[15] But opinions were different up at the Capitol. In reality, the rest of Congress seemed uninterested in the poor people’s plight. Republican House leader Gerald Ford observed that the campaign had had “no noticeable impact.”[16]

Unfortunately for the protesters, misfortune continued. Resurrection City’s living permit was due to expire on June 24, and some residents had begun to attack the police and tourists who lingered on the outskirts of the camp. It became clearer to many that the campaign had an expiration date, and SCLC leaders began to plan a monumental protest for June 19 as a last hurrah. In a tribute to King, they planned for thousands of people to congregate in front of the Lincoln Memorial, and for speeches to be made from where he made his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. The day was coined Solidarity Day.

The morning of June 19, 1968 was blessedly sunny. In a final cry of hope for the country’s poor, over 50,000 people marched to the Lincoln Memorial and surrounded the Reflecting Pool. Songs were sung, prayers sent up, and Coretta Scott King addressed the crowd. The day was indeed a day of solidarity, and one Afro-American reporter was touched by how the “determined and courageous spirits of the poor broke through under the brooding eyes of Lincoln for the world – and more pointedly – for the US Congress to see.”[17] The day was the crowning glory of the Poor People’s Campaign, but it didn’t have the lasting impact that many hoped it would.

Just three days after the success of the march, a number of Resurrection City youths allegedly threw fire bombs at passing motorists. It was the peak of violence that had accumulated over the past few weeks, and with less than 24 hours left of the camp’s permit, police decided to move in with tear gas. SCLC leader Andrew Young, who was at the camp that morning of June 23, was shocked. “It was worse than anything I saw in Mississippi or Alabama,” he said. “You don’t shoot tear gas into an entire city because two or three hooligans are throwing rocks.”[18] The gas cleared out most of the city, but a special Civil Disturbance Squad came the next day to officially shut it down. Most of the remaining residents were at the City Hall, “waiting good naturedly to be arrested and taken away.”[19] Freedom songs were broadcast over the city’s intercom system as they were marched off to waiting buses. While the campaign had ended, its spirit remained.

Footnotes

- ^ “Dr. King Maps Strategy for ‘Civil Disobedience,’” Afro-American, 9 December 1967.

- ^ “Can America End Poverty?” 1968, University System of Georgia, accessed 1 July 2015, http://crdl.usg.edu/events/poor_peoples_campaign

- ^ Freedman, Jill, Old News: Resurrection City, (New York: Grossman, 1970), 1.

- ^ “Economic and Social Bill of Rights,” 6 February 1968, The King Center, accessed 6 July 2015, www.thekingcenter.org/archive/document/economic-social-bill-rights

- ^ Bernstein, Carl and Peter Milius, “First Marchers Due Today,” The Washington Post, 12 May 1968.

- ^ “U.S. Issues Permit to March of Poor,” The New York Times, 11 May 1968.

- ^ Franklin, Ben A., “Capital Prepares for Poor’s March,” The New York Times, 12 May 1968.

- ^ Franklin, Ben A., “5,000 Open Poor People’s Campaign in Washington,” The New York Times, 13 May 1968.

- ^ Stout, Jared, “Marchers’ ‘City’ Rises,” The Washington Post, 13 May 1968.

- ^ Freedman, Old News, 31.

- ^ Valentine, Paul. “Abernathy Set to Start Protests,” The Washington Post, 21 May 1968.

- ^ “18 Marchers Arrested in Hill Protest,” The Washington Post, 24 May 1968.

- ^ Robertson, Nan, “City of the Poor Develops Style All Its Own,” The New York Times, 24 May 1968.

- ^ Freedman, Old News.

- ^ White, Jean and Willard Clopton, Jr., “Hill Delegation Visits Resurrection City, Promises Hearings,” The Washington Post, 6 June 1968.

- ^ “White, Jean M., “Ford Says Poor’s Campaign Stirs ‘No Noticeable Impact’ on Congress,” The Washington Post, 23 May 1968.

- ^ Sloan, David E., “Solidarity Day Brings Unity,” Afro-American, 22 June 1968.

- ^ Gilbert, Ben W., Ten Blocks from the White House (New York: Praeger, 1969), 202.

- ^ Kaiser, Robert G. “Resurrection City Falls – With a Song,” The Washington Post, 25 June 1968.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)