Fire and Rain: The Storm That Changed D.C. History

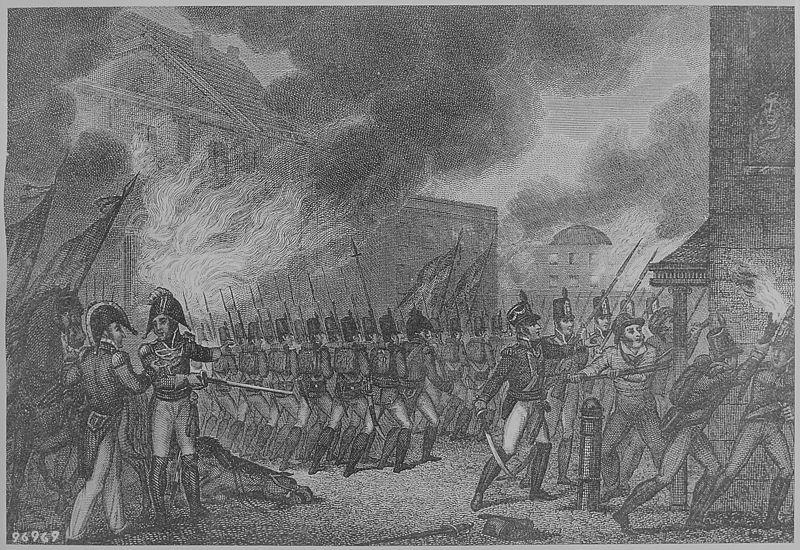

On Aug. 24, 1814, for the first and only time in our country’s history, Washington, D.C. was overrun by an invading army. The British army had easily defeated inexperienced American defenders, and set the city ablaze. The President had fled to Brookeville, MD,[1] and many of the citizens had fled along with the army. Those few residents of the capital who hadn’t already fled may well have prayed for anything that could stop the flames. What they got, however, was something far more than they were hoping for: a "tornado" more powerful than any storm in living memory.

When the British first took the city, they set fire to many buildings around the city, including the Capitol and the White House.[2] The fires were still burning the next day, exacerbated by temperatures reportedly exceeding 100℉, doing such damage that Congress was forced to carry on in temporary quarters once they eventually returned to the city, while their halls were being rebuilt. The capital was completely occupied, and the mayors of neighboring Georgetown and Alexandria surrendered to British General Cockburn in exchange for their cities being spared.[3]

Even before the storm, however, the British had suffered a significant setback: when some of their soldiers came upon 130 barrels of American gunpowder, they inexplicably decided to throw them down a well, where an inadvertent spark set off a huge explosion that left thirty British dead, forty-seven severely wounded, and a forty-foot crater.[4] Nearby buildings that were already on fire were knocked to the ground, and soldiers had to dodge “huge clods of earth” as well as bricks, cannonballs, and other debris that had been tossed into the air. This only added to the terror the residents felt, as many of them thought the shelling had begun again.[5]

Still, the British had the city safely under their control and had no cause to worry until around midday on the 25th. American reinforcements had arrived, and a force reportedly numbering almost 12,000 was massing a few miles from the city to face the British lines on Capitol Hill.[6] In the early afternoon, as the American forces began moving for a counterattack, however, the sky began to darken until it seemed like nighttime, and the rain began to fall.[5][6]

Modern and historical accounts differ over whether the storm was a tornado or a full-fledged hurricane; the words “tornado” and “hurricane” were used pretty much interchangeably back then, and an early definition of “tornado” was simply a tropical thunderstorm, so it’s difficult to say exactly what type of storm it was.[7] Whatever it was, however, its effect was enormous. The rain poured down, soaking troops from both sides and, incidentally, putting out most of the fires the British set. Then as now, Washingtonians were used to summer storms bringing sudden and torrential downpours. The winds, however, were something they could not have prepared for. Homes collapsed or were lifted off their foundations. Trees were uprooted, and chimneys and roofs went flying through the air. Even light cannons were lifted off the ground and blown back “several yards.”[8] Supposedly, more British were killed by debris thrown around by the tornado than by American defenders, which is more of a testimony to the ineffectiveness of American regulars than the power of the storm.[9]

Attempting to do battle in the middle of a hurricane was, needless to say, fruitless. The chaos was absolute. Any orders or battle cries were drowned out by the roar of the wind and the crash of thunder. The British, who had previously humiliated the Americans at Bladensburg with a greater show of discipline, broke ranks and scattered like paper soldiers under the strength of the cyclone. One officer, riding his horse around a corner, inadvertently rode directly into the oncoming wind, and “[i]n an instant both he and his horse were blown to the ground.”[10]

George Robert Gleig, a British soldier, later remembered the scene:

Of the prodigious force of the wind it is impossible for you to form any conception...The darkness was as great as if the sun had long set and the last remains of twilight had come on, occasionally relieved by flashes of vivid lightning streaming through it; which, together with the noise of the wind and the thunder, the crash of falling buildings, and the tearing of roofs as they were stript from the walls, produced the most appalling effect I ever have, and probably ever shall, witness. This lasted for nearly two hours without intermission, during which time many of the houses spared by us were blown down and thirty of our men, besides several of the inhabitants, buried beneath their ruins. Our column was as completely dispersed as if it had received a total defeat, some of the men flying for shelter behind walls and buildings and others falling flat upon the ground to prevent themselves from being carried away by the tempest.[11]

Trying to impose an 8 p.m. curfew was pointless, as soldiers staggered around in gale-force winds. Two hours later, the storm finally died down, but the damage had been done.[12] The putative battlefield had been ravaged without a shot being fired. The British seized the opportunity to sneak away in the night, leaving their campfires blazing to cover their escape.[13]

Amidst the wreckage, both sides moved to put on rosy glasses and claim they had actually benefited from the storm. Many (American) retellings of this story depict the tornado as “the storm that saved Washington,” but in reality, the storm did just as much damage as the British invaders.[14] On the other side, Gleig claimed that the storm presented the ideal opportunity for British Major General Robert Ross’ retreat: “When the hurricane had blown over, the camp of the Americans looked to be in as great a state of confusion as our own...Of this, General Ross did not fail to take advantage. He had already attained all that he could hope, and perhaps more than he originally expected to gain...To avoid fighting was, therefore, his object, and perhaps he owed its accomplishment to the fortunate occurence of the storm.”[15]

The two sides’ conflicting attitudes can be summed up by a famous, probably apocryphal quote, but one without which no account of the tornado can be complete. It concerns a supposed conversation between a British admiral and an American woman who had remained in Washington throughout the chaos:

The admiral exclaimed, “Great God, Madam! Is this the kind of storm to which you are accustomed in this infernal country?” The lady answered, “No, Sir, this is a special interposition of Providence to drive our enemies from our city.” The admiral replied, “Not so Madam. It is rather to aid your enemies in the destruction of your city.”[16]

Whatever either side might claim, the storm foiled the plans of both armies. Still, whatever the reason, the storm heralded the British departure from the capital, leaving the Washingtonians free to pick up the pieces. It’s not every day that a war is called off due to the weather, but as DC residents can attest, you have to be prepared for anything; the British planned their invasion well, but they didn’t plan for Washington weather.

For more on George Robert Gleig's impression of Washington as an "infant town," and his distaste with its "air of republicanism," click here.

Footnotes

- ^ As a British man told it, President Madison “had continued with his troops till the British forces began to make an appearance”, whereupon he “began to discover that his presence was more wanted in the senate than in the field.” (George Robert Gleig, “The campaigns of the British army at Washington and New Orleans, in the years 1814-1815,” (London: J. Murray, 1827), 133-4.)

- ^ As is often repeated in accounts of the British invasion of Washington, British soldiers ate the victory dinner already set out for the American officers at the White House before setting the place on fire.

- ^ A.J. Langguth, Union 1812: The Americans Who Fought the Second War of Independence, (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006), 309-311.

- ^ Anthony S. Pitch, The Burning of Washington: The British Invasion of 1814, (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1998), 138.

- a, b Pitch, The Burning of Washington, 139.

- a, b Gleig, “The campaigns of the British army,” 141.

- ^ Some accounts claim it was three tornadoes, while others say it was a hurricane that caused a tornado or two. The point is, it was pretty windy out there.

- ^ Gleig, “The campaigns of the British army,” 142.

- ^ National Weather Service, “D.C. Listing of Historical Tornadoes,” last accessed July 15, 2015, http://www.erh.noaa.gov/er/lwx/Historic_Events/DC-tornado-events.htm

- ^ Pitch, The Burning of Washington, 140.

- ^ Gleig, “The campaigns of the British army,” 141-2.

- ^ A.J. Langguth, Union 1812: The Americans Who Fought the Second War of Independence, (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006), 310.

- ^ Pitch, The Burning of Washington, 143-4. The fleet, which had been in the harbor and also borne a fair amount of damage from the storm, retreated to Bermuda - and you know things are bad when you’re going to Bermuda to get away from a hurricane.

- ^ As a local newspaper glumly concluded, “nature and man seem to have marked our city for destruction.” ([no headline; British, Bladensburg], National Advocate, September 6, 1814.)

- ^ Gleig, “The campaigns of the British army,” 143.

- ^ Kevin Ambrose, Dan Henry, and Andy Weiss, “The Tornado and the Burning of Washington, August 25, 1814,” last accessed July 15, 2015,http://www.weatherbook.com/1814.htm. Excerpted from Ambrose, Henry, and Weiss, Washington Weather: The Weather Sourcebook for the DC Area, (Historical Enterprises, 2002)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)