The Thwarted Plot to Kill Lincoln on the Streets of Baltimore

Abraham Lincoln’s election to the presidency on November 6, 1860, was the catalyst for vehement anger in the South, where the wave of secession had already begun to stir. The anger at the president-elect became so great that several conspirators vowed he would never reach the capitol to be inaugurated.

By many accounts, Lincoln was aware but unmoved by the threats that rose around him in early 1861 as he prepared to relocate from his home in Springfield, Illinois to the White House. He planned a grand 2,000-mile whistle-stop tour that would take his train through seventy cities and towns on the way to his inauguration. He was sure to be greeted by thousands of well-wishers, but a more sinister element was also gathering.

Lincoln’s trusted aide John Nicolay would later note, “His mail was infested with brutal and vulgar menace…but he had himself so sane a mind, and a heart so kindly, even to his enemies, that it was hard for him to believe in political hatred so deadly as to lead to murder.”[1]

While Nicolay privately worried about Lincoln’s safety in advance of his Feb. 11 departure for Washington, railway executive Samuel Morse Felton had concerns of his own.

Felton, president of the Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore Railroad, had received information that secessionist plotters were developing a “deep-laid conspiracy to capture Washington, destroy all the avenues leading to it from the North, East, and West, and thus prevent the inauguration of Mr. Lincoln in the Capitol of the country.”[2]

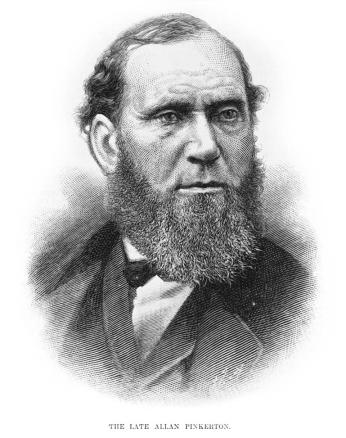

Felton turned to Allan Pinkerton, founder of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, for help in investigating the matter. Pinkerton would later come to be known as the country’s first “private eye,” but he already had a reputation as a dedicated and clever investigator.[3] He immediately set off for Baltimore, Maryland, the suspected focus of the plot Felton feared to be underway.

The fate of Maryland was on all minds north and south in the days leading up to the Civil War. South Carolina actively courted the slave-practicing state, and it was home to its fair share of anti-Union sentiment. It bordered Washington, D.C. on three sides, and the capitol’s telegraph and rail links north and west ran over Maryland soil. If the state seceded, the federal government would have no choice but to abandon Washington, an action that would heavily favor the nascent Confederacy.[4]

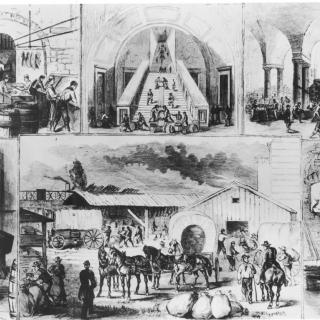

Pinkerton and his fellow detectives traveled to Baltimore under assumed identities to infiltrate secessionist circles. They found a city quite stirred up by Lincoln’s impending arrival on Saturday, Feb. 23. The president-elect had published his itinerary, and he was scheduled to arrive at Calvert Street Station in Baltimore at 12:30 p.m. on the Northern Central Railway, and then depart on the Baltimore & Ohio train from Camden Street Station at 3:00 p.m. The two stations were about a mile apart.

While Lincoln’s train made its way through the northern states on its way to Baltimore, Pinkerton was piecing together the plot against him. Posing as a southern stockbroker named John Hutchinson, Pinkerton set up a suite of offices at 44 South Street. He and his fellow agents frequented local saloons and restaurants to connect with secessionist elements. One particular hotbed of Confederate sympathizers was Barnum’s Hotel at Calvert and Fayette Streets.

Through their investigations at Barnum’s, Pinkerton and his agents met Capt. Cypriano Ferrandini. Ferrandini, a Corsican immigrant, was a barber who worked out of Barnum’s basement, and he was thoroughly dedicated to the Southern cause.

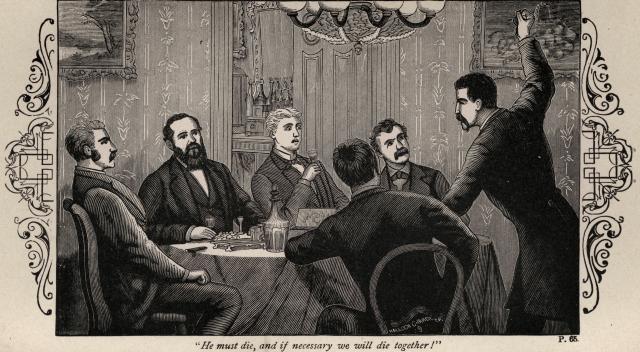

“Lincoln shall never, never be president,” Ferrandini said. “My life is of no consequence. I am willing to give it for his. I will sell my life for that of that abolitionist.”[5]

Pinkerton and his agents discovered that Ferrandini and his men planned to assassinate Lincoln during his one-mile transition between the Calvert Street and Camden Street stations on February 23. One of two methods was anticipated. The first being a standard diversion tactic that would draw the attention of the small police force on site, allowing one man to reach the president-elect and kill him. A second method called for having several assassins in the crowd, counting on any one of them to get close enough to kill Lincoln.

Either way, Pinkerton knew Lincoln’s life was in grave danger. He got word to Lincoln about the plot and then set about creating an alternate plan that would confound Ferrandini and his co-conspirators.

On Feb. 22, while dining at the Jones House in Harrisburg in the company of Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin, Lincoln feigned exhaustion and retired for the evening. He slipped out a side door and into a waiting carriage wearing a wool hat and shawl. He walked hunched to disguise his tall frame. He boarded a Pennsylvania Railroad train for Philadelphia at 6:00 p.m., then switched to an 11:00 p.m. Baltimore-bound train on Felton’s PW&B line.[6]

Lincoln arrived at President Street Station in Baltimore at 3:30 a.m. on Feb. 23. Pinkerton managed to bring him into town several hours ahead of schedule, on a different train, and into a different station, changing every item on the itinerary.[7]

It was at this point that Pinkerton’s plan was most in danger of unraveling. A Baltimore ordnance prevented rail travel within the city at night, so Lincoln’s car had to be unhitched and drawn by horses through town to the Camden Street station where the connecting train would be departing. As they slowly creaked through the streets, Lincoln, Pinkerton, and the others in the small group could hear the sounds of “Dixie” being sung by drunken Southern revelers.

As dawn approached, the advantage of stealth began to melt away. Pinkerton knew that if word of Lincoln’s presence got out and a mob formed, his ability to protect the president-elect would be greatly diminished. Yet, the car was recoupled to a waiting Baltimore & Ohio in due course and was soon out of Baltimore, arriving in Washington at 6:00 a.m. on Feb. 23.

Ferrandini and his co-conspirators were angered at being cheated out of their chance to kill Lincoln.[8] The president-elect would receive a great deal of criticism for sneaking through Baltimore, and Lincoln himself had said, “What would the nation think of its President stealing into the Capital like a thief in the night?”[9]

Pinkerton, however, remained sure of his actions and proud of his deed. He wept at the news of Lincoln’s assassination in 1865, lamenting that he had not been there to protect the president.

Footnotes

- ^ Daniel Stashower, “The Unsuccessful Plot to Kill Abraham Lincoln,” Smithsonian Magazine, February 2013. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-unsuccessful-plot-to-kill-abr…

- ^ Stashower, “The Unsuccessful Plot to Kill Abraham Lincoln.”

- ^ PBS.org, “Allan Pinkerton’s Detective Agency,” http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/biography/james-age….

- ^ William E. Gienapp, “Abraham Lincoln and the Border States,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, Volume 13, Issue 1, 1992, p. 14.

- ^ Isaac H. Arnold, “The Baltimore Plot to Assassinate Abraham Lincoln,” Harper’s, June 1868, p. 125.

- ^ Arnold, “The Baltimore Plot to Assassinate Abraham Lincoln,” p. 127.

- ^ Stashower, “The Unsuccessful Plot to Kill Abraham Lincoln.”

- ^ Cypriano Ferrandini remained an avid secessionist, and although questioned for his activities, was never arrested for his role in the Baltimore Plot.

- ^ Deirdre Donahue, “’Hour of Peril’ explores the first plot against Lincoln,” USA Today, January 29, 2013, http://www.usatoday.com/story/life/books/2013/01/29/lincoln-plot-assass….

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)