Julius Hobson's Unlikely Relationship with the F.B.I.

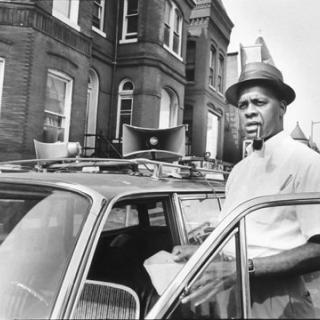

We’ve written before on this blog about the exploits of Julius Hobson. A D.C. civil rights activist in the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s, his campaigns against segregation and injustice were based on equal parts audacity and bluff, ranging from staging a “lie-in” at a D.C. hospital, to encouraging people to paste pro-integration stickers over the punchcards on their power bills,[1] to threatening massive protests and boycotts that had no chance of materializing. He combated police brutality by following policemen around with a long-range microphone, and, most famously, promised to release cages full of rats on Georgetown if the city didn’t deal with the rat problem elsewhere. His antics effected genuine social change, in large part because everyone was too nervous to call him on his bluffs, for fear that he might be able to back them up. His acts were already so outlandish, anything seemed plausible, except for one rumor that seemed to be too uncharacteristic to be true. Yet, it was the truth: for years, Julius Hobson passed information to the FBI.

In May of 1963, the FBI first approached him as part of a program where the Bureau looked for civil rights leaders willing to “furnish the Bureau advance information concerning demonstrations.”[2][3] According to their documents, Hobson cooperated enthusiastically with investigators.[4] For several years, until 1966, he gave the FBI information on upcoming civil rights demonstrations and conventions, including events like the March on Washington.

What was his motivation to do this? As a self-described “Marxist Socialist,” he was on the Bureau’s watch list himself.[5] Those who knew him insisted that this was another one of his tricks, that Hobson, that master of manipulation, was deliberately feeding the Bureau false information to confuse them. One anonymous CORE activist told a story about a protest in front of the Justice Department:

"These two FBI agents came up to Julius, took him aside and talked to him for a few minutes," he said. "When Julius came back, he said they had asked him who organized the demonstration and he told them King had done it from his jail cell in Alabama. . . . He did that kind of thing."[6]

If anyone would be audacious enough to try and trick the FBI, it would be Hobson. Still, the King story, which seems like it would have been of great interest to the FBI, does not appear in any of the released files; however, some of the files have reportedly been destroyed,[6] and a few are heavily censored.

Hobson met with agents pretty regularly,[7] reporting on some civil rights action every few weeks during 1964 and 1965. Hobson seemed to inform mostly on his own plans. He let the FBI know that his planned “Seven Days in May” would not be a drastic citywide attempted shutdown of the federal government, as the press believed, but merely a few protests at discrete locations, none with more than a hundred people.[2] All sources agree he was “privately opposed to violence and illegality,” although his public rhetoric occasionally called for revolution.[6]He seems to have mostly informed to warn the Bureau about protests he feared would turn violent, or refute the more serious charges printed in the papers (for example, that his organization, the Associated Community Teams, was affiliated with violent militants.) Hobson’s goal, it appeared, was to get the law to leave his protests alone.

However, he did inform several times on certain individuals’ activities and presence at his events, most notably Lawrence Landry, Gloria Richardson, and those associated with the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM), such as Don Freeman. (RAM was a militant movement that advocated arming oneself for self-defense.) Hobson evidently considered these leaders dangerous, and once even told them to cancel their plans to attend an event in D.C. This seems to have been mainly to get the attention of the Bureau off of his protests. Hobson would advance his cause by any means he could think of, including passing information to the Feds to get the pressure off his organization.

The most baffling report in the whole file is that Hobson accepted $100 from the FBI for expenses while on a mission to “disrupt” the protests at the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, although he seems to have had second thoughts and left before the convention started.[6] His first wife, Carol Smith, claims that this, too, was a trick; according to her, Hobson supposedly milked the Bureau for money and distributed it to activists who would not have otherwise been able to make the trip to the convention.[6] Agents he contacted, however, reported that he provided them with a wealth of useful information, while his second wife Tina Hobson claimed later that Hobson fabricated information about fictional demonstration plans and gave it to the FBI in order to confuse and discredit them.[6] This is characteristic of the whole mess; where Hobson is concerned, it is very difficult to discern between truth, tricks, and legends.

One thing is for certain, however: Hobson never told them about the rats.

After a few years, though, his liaison came to an abrupt end. In June 1966, Hobson commented to the press that “FBI agents had been contacting him all week” about the recent demonstrations of the New York Committee. The FBI promptly dropped him as a source, declaring in an internal memo that Hobson should be “discontinued” because “he talks from both sides of his mouth” (apparently a quote from a furious J. Edgar Hoover).[2] There are no more records of contact after this point. Perhaps Hobson simply got fed up with working for the FBI, or maybe it was a slip of the tongue. Whatever the reason, Hobson and the FBI had parted ways for good.

His activism did not end with his informant status, however, and he continued to be as disruptive as ever, pushing for reforms in various areas of D.C. policy, including challenging the public schools’ “track system” in court, and spearheading the D.C. Statehood campaign. The House of Representatives even passed a resolution specifically aimed at him, declaring that they would “bar funds for salaries of federal employes [sic] who incite riots and other illegal civil disturbances or encourage people to do so.”[8] (Hobson worked for the Social Security Administration as a statistician.) Hobson was undeterred, and continued to fight for social change until his untimely death of cancer in 1977, pushing for a bill to give D.C. residents the ability to recall City Council members at a Council meeting just the day before his death.[9]

More Information

Most of the information in this article comes from the Julius Hobson Papers in the Washingtoniana division of Martin Luther King, Jr. Library in DC. The papers contain an entire box of FBI files on Hobson, as well as odder tidbits like his X-rays from 1972. If you’re interested in Hobson, they’re definitely worth checking out.

Footnotes

- ^ To protest then-segregated Pepco’s policies.

- a, b, c DC Public Library, Washingtoniana Division, Collection 1, Julius Hobson Papers.

- ^ Although some sources claim Hobson and the FBI had contact as early as 1961. (Paul W. Valentine, “FBI Records List Julius Hobson As Confidential Source,” Washington Post, May 22, 1981.)

- ^ In a memo dated May 28, 1963, it is noted that “[Hobson] has been extremely cooperative in regards to applicant and other type inquiries…” DC Public Library, Washingtoniana Division, Collection 1, Julius Hobson Papers.

- ^ The FBI described him as “a Negro ‘radical’ who thrives on free publicity.”

- a, b, c, d, e, f Paul W. Valentine, “FBI Records List Julius Hobson As Confidential Source,” Washington Post, May 22, 1981.

- ^ “‘We'd visit him at HEW [where Hobson worked] and have a cup of coffee with him. . . He kept his eyes and ears open’... Todd said the FBI initiated most contacts with Hobson, ‘but sometimes he called us.’” (Paul W. Valentine, “FBI Records List Julius Hobson As Confidential Source,” Washington Post, May 22, 1981.)

- ^ “House Moves to Block Hobson Pay,” Evening Star, May 26, 1967.

- ^ “Alabama Native Hobson Died A Rebellious Man,” Florence Times + Tri-Cities Daily, March 29, 1977; “Recall proposal advances in D.C.,” The Free Lance-Star, April 6, 1977.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)