Julius Hobson Fought Racism with Rats

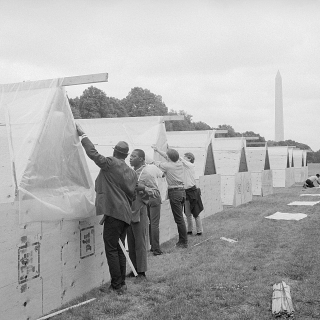

If you lived in DC in August 1964, you might have seen Julius Hobson driving through downtown with a cage full of enormous rats strapped to the roof of his station wagon. Frustrated by the city government’s refusal to do anything about the rat problem in Northeast and Southeast DC, and about the District’s more affluent citizens’ apathy about the issue, he said that if Southeast was having this problem, then Georgetown should share it too. Hobson caught “possum-sized rats” in Shaw and Northeast, and transported them up to Georgetown, promising to release the cage full of rats in the middle of the wealthy district unless the city government acted to curb the epidemic.[1] Since he was, as a piece in The Washingtonian put it, “[a]ware that a DC problem usually is not a problem until it is a white problem,”[2] he decided to go ahead and make it a white problem.

Every Saturday, Hobson would have almost a dozen huge rats on top of his car, hosting “rat rallies” where he would loudly reiterate his threats. He claimed to have a “rat farm” somewhere in the city, where he and his associates had “chicken coops” full of rats, and they vowed to release them all unless the government implemented rat extermination programs that would range outside of rich and white neighborhoods.[3] What’s more, Hobson had done his research and found he had no legal obligation to keep the rats once he caught them, so he could not be prosecuted for following through on his threat. As many of the city officials (not to mention Congressmen) lived in Georgetown, this, naturally, sent the city government into a panic.

This was not the first or last time Hobson would use such gonzo tactics. Hobson saw a problem and attacked it head-on; his preferred technique for integrating businesses was to march up to the owner with several other activists behind him and demand the store integrate. When police brutality in DC towards minorities became a publically discussed issue in the 1960s, but there was no proof of their misconduct, Hobson simply built a long-range microphone (he had a degree in engineering) and drove around after police cars, collecting evidence.[4][5]

The “rat project,” however, remains one of Hobson’s most famous tricks, for precisely the reason it succeeded: the press latched onto it like a rat onto a hunk of cheese. Newspapers across the District seized upon the story and embellished it. In the retelling, his rat-catching protest became “a caravan of cars with cages”[6] or “two hundred dead rats” that Hobson had supposedly dumped in the middle of a Georgetown street.[7] One recent article even claimed that “Hobson vowed to load rats into a truck and dump them in ... the White House.”[8] This was one of Hobson’s favorite techniques: doing something sensational and letting the press blow it out of proportion, making him seem to command much more power and influence than he actually did. In a later interview with the Washington Post, Hobson laughingly thanked the paper for being so helpful to his causes.[9]

A lot of his activism, too, was based on what he described variously as “psychological warfare” and “bluffs."[9] In reality, Hobson never had more than ten rats at a time. As Hobson later admitted: “Actually, what we were doing was drowning the hell out of those rats after dark.”[9] In another instance, Hobson threatened to shut down Route 40, site of numerous segregated restaurants, with massive protests, when in reality Hobson would have at most fifty people at his disposal.[10] As for his famous long-range microphone, Hobson admitted it didn’t really have a range of more than a few feet. But the stores, and the police department, changed their policies. You never knew when he would actually follow through on his threats, so it was never safe to call him on his bluffs.[11]

However unorthodox they were, Hobson’s strategies were undeniably effective. In the rat protest’s case, the results were almost immediate: after some panicked phone calls, the district funded rat patrols for Northeast and Southeast.[9]

Reminiscing about the operation in later years, Hobson said that despite the fact that he never had more than a dozen rats, he had intended to fulfill at least part of his promise if the city didn’t back down: “I was going to turn those rats loose on Georgetown,” he said. “The fact of the matter was, it was hell to catch those damn rats.”[9]

More Information

Among Hobson’s other notable accomplishments are his role in desegregating DC public schools and dismantling their “track system” (in Hobson v. Hansen), his term on the school board, his pickets and boycotts that led to the desegregation of hundreds of DC businesses, his “lie-in” at Washington Hospital Center that helped end segregation there, his spearheading of the DC statehood campaign and founding of the DC Statehood Party (now the DC Statehood Green Party), his candidacy for Vice President of the US in 1972 on the People’s Party ticket with Benjamin Spock, and his term on the DC City Council from its inception in 1974 until his death in 1977.

Hobson’s own publications on social issues and activism, “The Damned…” series, are definitely worth a read. His titles are The Damned Children: A Layman’s Guide to Forcing Change in Public Education and The Damned Information: Acquiring and Using Public Information to Force Social Change. They are available in the Washingtoniana room of the District’s MLK Library and elsewhere.

The Washingtoniana room also holds the Julius Hobson Papers, a ridiculously extensive collection of Hobson’s personal letters and papers, as well as articles about him and various biographical documents. Here you can find things like a letter from Joan Baez about a protest the two had just been a part of, FBI files concerning his activities, and even (creepily enough) his x-rays from a check-up in 1972.

Footnotes

- ^ Cynthia Gorney, “Julius Hobson Sr., Activist, Dies at Age 54,”Washington Post, March 24, 1977.

- ^ Charles N. Conconi, “Goodbye, Mr. Hobson: The Last Interview,” The Washingtonian, 136.

- ^ “Hobson Specialty: Successful Hoaxes,” Washington Post, July 4, 1972.

- ^ Gorney, “Julius Hobson Dies at 54,” Washington Post.

- ^ You get the idea, but this story is too good to not merit at least a footnote: Hobson used to go to boardroom negotiations with segregated businessowners with Paul Bennett, who wore a disheveled WWI mackinaw and flyer’s cap, and constantly spit into a handkerchief. The two of them had an agreement that whenever Hobson would pretend to work out a compromise with the businessowners, Bennett would jump up and call him an Uncle Tom. This went a long way towards achieving their full capitulation. (Bennett’s appearance was deceiving: he was actually a GS-12 employee of the Department of the Navy, with a master’s degree in physics. Hobson: “But for some reason he wore those clothes. I never could understand why he wore those clothes.”) Source: “Hobson Specialty: Successful Hoaxes,” Washington Post, July 4, 1972. This whole article is pure gold, by the way. I highly recommend reading it if you get the chance.

- ^ Raymond Wolters, Race and Education, 1954-2007, (University of Missouri Press, 2009), 72.

- ^ Robert F. Levey, “City Barely Keeps Even in War on Rats: City 'Barely Keeps Even' in Rat War,” Washington Post, January 30, 1972.

- ^ Harry Jaffe, “D.C. Pols Are Home Fools For Julius Hobson Sr.,”Washington Examiner, April 18, 2011.

- a, b, c, d, e “Hobson Specialty: Successful Hoaxes,” Washington Post, July 4, 1972.

- ^ Burt Solomon, The Washington Century: Three Families and the Shaping of the Nation’s Capital, (HarperCollins, 2005), 125.

- ^ Hobson’s manipulation of information even went as far up as the FBI, as he passed them information concerning his own activities and protests. Accounts differ as to whether he was giving them information to curb “violence and illegality” in the civil rights movement, or simply “discrediting them with false information,” but either way, his objective was the same: using the system to make things easier for his protests. (Paul W. Valentine, “FBI Records List Julius Hobson As Confidential Source,” Washington Post, May 22, 1981.)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)