Jackie Robinson and the House Un-American Activities Committee

Jackie Robinson, who integrated Major League Baseball in 1947, faced intense pressure. On the field the Brooklyn Dodgers star had to prove himself as a player, avoid rising to provocations and maintain an exemplary public image. Off the field, he had to deal with powerful people who sought to manipulate and misuse his fame, without hurting the African-American community that he was struggling to uplift.

One of Robinson's most difficult moments came on July 18, 1949, when he reluctantly appeared as a witness before the House Un-American Activities Committee, the long-defunct Congressional panel whose ostensible mission was to ferret out disloyalty and subversion in American society. The HUAC's aim was to have Robinson discredit a previous witness, actor and civil rights activist Paul Robeson. Robinson felt he had no choice but to comply — a decision he came to regret. But somehow, even while he served the committee's purposes, Robinson also managed to use the occasion to speak out about racial injustice, just as Robeson had.

Founded in 1938 as a temporary committee, the HUAC started out investigating domestic fascist groups, but opponents of President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal soon began using it to attack FDR's programs and making dark accusations of communist influence. In 1945, committee member Rep. John E. Rankin of Mississippi managed to convince the House rank-and-file to buck its leadership and make the HUAC a permanent institution. Rankin was both a fervent anti-communist and a white supremacist, and in his conspiracy-loving mind, those two causes apparently dovetailed. Rankin explained in a 1947 speech, he believed that blacks who sought civil rights were in league with communists in an effort to thwart his dream of being elected to the U.S. Senate. "They sneer at me because of my advocacy of white supremacy — the only system under which we can hope to live and prosper and be peaceful in the southern states," he said.

Robeson was one of those perceived enemies. The HUAC had summoned him to testify in April 1949 about his statement — in a speech and a newspaper essay — that it was "unthinkable" that oppressed blacks would go to war against the Soviet Union. When the eloquent and unflappable Robeson wouldn't back down, the committee sought out another African-American icon to refute his position. Unfortunately for Robinson, his notoriety as the first black major league player made him perfect for the role.

As Robinson recalled in his memoir, I Never Had It Made, he got a telegram from a committee member, Georgia Rep. John S. Wood, asking him to appear and put the lie to Robeson. Robinson recalled that he felt deeply conflicted, and sought advice from his wife Rachel. While he didn't agree with what Robeson had said about blacks being reluctant to fight for their country against the Soviets and even found it disturbing, he admired Robeson and sympathized with his struggles against bigotry. Moreover, "I didn't want to fall prey to the white man's game and allow myself to be pitted against another black man," he wrote. "I knew that Robeson was striking out against racial inequality in the way that seemed best to him." All the same, Robinson didn't believe that Robeson had the right to speak for all African-Americans, and he feared that Robeson's statement — and his ties to communists and the Soviet Union — might serve to discredit his race in the eyes of whites. So he reluctantly accepted the invitation.

But while the HUAC wanted Robinson, many other African-Americans and civil rights supporters were horrified. They deluged the baseball star with letters, telegrams, and phone calls urging him to decline to appear. Robinson believed that at least some of those missives were part of an organized communist campaign, but he knew that others were genuine expressions of dismay. Even so, he felt that he had to do it.

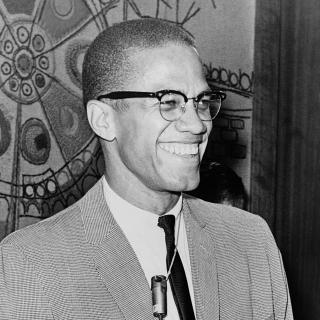

And so, on July 18, Robinson — clad in a dapper wide-lapelled suit — sat down in front of a microphone, and read his statement from papers that he held in his left hand. Robinson said that Robeson's statement about blacks not wanting to fight the Soviets "sounds very silly to me," while noting that "he's still a famous ex-athlete and a great singer and actor." As for African-Americans' loyalty to the U.S., Robinson said he believed that even though some undoubtedly were communists and pacifists, he believed that they — like other ethnic and racial groups — would "do their best to help their country win the war, against Russia or any other enemy that threatened us."

Robinson questioned Robeson's credibility in speaking for all members of his race. As for himself, Robinson said, "I am a religious man. Therefore I cherish America, where I am free to worship as I please, a privilege that other countries do not give. And I suspect that 999 out of almost any thousand colored Americans you meet will tell you the same thing."

But Robinson wasn't finished. His disagreement with Robeson and his own loyalty to the U.S. "doesn't mean that we're going to stop fighting race discrimination in this country until we've got it all licked," he said. "It means that we're going to fight all the harder because our stake in the future is so big. We can win our fight without the communists and we don't want their help." Robinson also carefully drew a distinction between the fight against racial discrimination and communist ideology: "the fact that it is a communist who denounces injustice in the courts, police brutality, and lynching when it happens doesn't change the truth of his charges," and pointed out that racial discrimination is not "a creation of communist imagination."

Regardless of some of the nuances of his testimony, anti-communist conservatives applauded Robinson's appearance. Rep. Bernard W. "Pat" Kearney of New York was so pleased with them that he recommended that the Veterans of Foreign Wars honor Robinson with a gold medal for good citizenship. The baseball star had demonstrated that he was "a real American citizen," Kearney told a reporter.

Not everyone had the same view. The FBI, which maintained a file on Robinson, continued to monitor his activities in the civil rights movement for years after he left baseball, amassing intelligence from informants and gathering coverage about him in African-American newspapers.

As historian Philip S. Foner pointed out in a 1987 letter to the New York Times, there was a sad irony to it all. Robeson, after all, had led a delegation of African-American leaders who'd met with Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis and major league owners, at the Roosevelt Hotel in New York City on Dec. 3, 1943, and lobbied them to allow black players. "The time has come when you must change your attitude toward Negroes," Robeson had explained. "Because baseball is a national game, it is up to baseball to see that discrimination does not become an American pattern." The commissioner and the owners had agreed, and two years later, Jackie Robinson had been signed to play on a farm team.

Robinson himself wrote in his memoirs that he regretted his decision to testify and attack Robeson. "In those days I had much more faith in the ultimate justice of the American white man than I have today," he wrote. "I would reject such an invitation if offered now."

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)