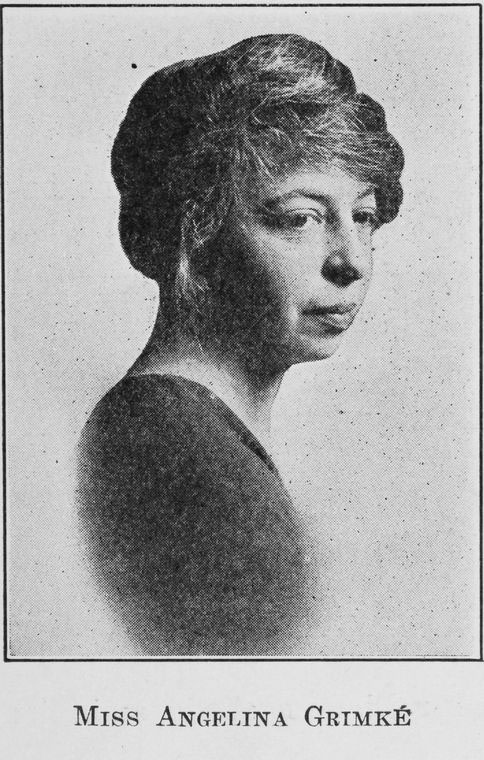

Art as Protest: Angelina Weld Grimké's "Rachel"

At the dawn of the twentieth century, the youngest member of the prominent African American Grimké family was beginning to establish a name for herself in the literary world. Born in 1880, Angelina Weld Grimké joined a long line of activists. Her uncle, Francis J. Grimké, was a D.C.-based, Princeton-trained theologian who help establish the NAACP. Her father, Archibald, was a Harvard Law School graduate, diplomat, newspaper publisher and activist. Angelina herself was named after her great aunt, Angelina Grimké Weld.[1] After graduating college, the younger Angelina relocated to Washington, D.C. and became a physical education teacher – first at Armstrong Manual Training School and then at the storied Dunbar High School.

With the financial stability of her teaching career, Grimké began to focus on her writing. She garnered critical acclaim for her poetry, much of which consisted of tributes to great African Americans, grief observances of nature’s beauty and Queer love poems. Lynching was another common theme in Grimké’s work as she began to employ her pen to affect change. She was prolific and, though largely overlooked today, helped usher in the Harlem Renaissance before Zora Neale Hurston, Nella Larsen and Langston Hughes became household names.

Grimké’s writings were published in the NAACP’s Crisis magazine, the National Urban League’s Opportunity journal and the Atlantic. Her work was later included in Alain Locke’s anthology of the Harlem Renaissance, The New Negro, published in 1925. Though her writings were widespread, it was one piece in particular that may have left the biggest impression, especially in Washington: Grimké’s 1916 play, “Rachel.”

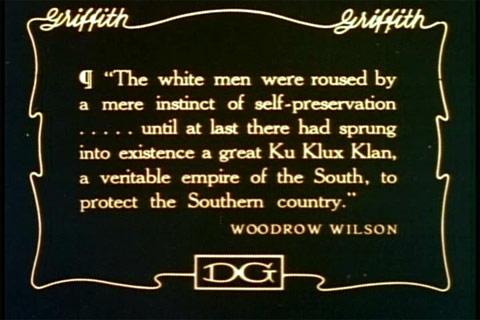

In 1915 race relations in the United States were on a steady decline. President Wilson welcomed Jim Crow to the federal government with open arms and rampant lynching tread crudely over the Bill of Rights. Hollywood’s first blockbuster The Birth of a Nation was a product of the tempestuous culture it would further shape.[2] At over three hours in length, director D.W. Griffith used visually-arresting filmmaking to retell U.S. History. In this distorted portrayal, the KKK was a gallant force that reunited the Republic following the Civil War.[3] Based on the 1905 novel The Clansman by Thomas Dixon, Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation was steeped in racist tropes of African American inferiority and criminal pathology. The film even included quotes from Woodrow Wilson’s A History of the American People, an entry into the Lost Cause historiography, which saw the Reconstruction as a period of retrogression.[4]

As the film became a hit with white audiences, it made the rounds among the most powerful circles in the U.S. In February 1915, The Birth of a Nation was the entertainment at a National Press Club banquet honoring U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Edward Douglass White. The press noted that 38 U.S. senators were some of the “500 spectators who cheered and applauded throughout.”[5] That same month, President Wilson – a former classmate of Thomas Dixon at Johns Hopkins – hosted a screening of the film at the White House for members of his cabinet with D.W. Griffith as a guest.[6]

In the African American community and on the left (including Jane Addams and Eugene Debs), the response to the film was much different and it became a lightning rod for protest.[7] In Boston, newspaper publisher William Monroe Trotter, staged a picket at a theater screening the film which led to five arrests and reports of a riot.[8] Amid backlash from African Americans, Chicago Mayor Carter Harrison prohibited screenings within the city. (He was overruled by Superior Court Judge William F. Cooper who ruled that the possibility for the film to “engender race animosity is based purely on an assumption.”[9]) The NAACP was a leading voice of protest.

Since its inception in 1909, the interracial NAACP was guided by a commitment to “attack segregation laws, investigate lynching, [and] defend the Negro in his civil rights.”[10] To better promote the organization’s aims, it launched the Crisis magazine, edited by W.E.B. Du Bois. In the Crisis, poems and short stories were interspersed between sharp editorials and columns like “The Burden”, which numerically documented the numbers of African American “men and women lynched without trial."[11] Indeed, for Du Bois and other NAACP leaders, highlighting works of art was a key tool in advancing the organization’s mission, in several ways.

As scholar Jenny Woodley observed, “There was more to the NAACP’s cultural strategy than simply proving that African Americans could create works of art and literature. The body of work in the Crisis helped to forge a collective black identity that was crucial to the NAACP’s fight. It created a sense of racial pride, not only by demonstrating the talent of fellow race members but also by foregrounding black faces and characters and black life.”[12]

Thus, as NAACP branches across the country were organizing boycotts around The Birth of a Nation in 1915, it’s no surprise that Angelina Weld Grimké looked toward the organization as an outlet for her latest work, a stage production called “Rachel.”[13] The stirring play takes place in “the first decade of the Twentieth Century” in an unnamed “northern city,” and focuses on the three member Loving family, a mother and her young adult children.[13] The idyllic household is disrupted in the play’s first act when the mother reveals to her children why she’d been acting strangely.

Mrs. Loving: “Ten years ago—today—your father and your half-brother died.’ Did it ever strike you as strange that they died the same day?”[14]

Rachel: “We often wondered, Tom and I; but somehow we never quite dared to ask you. You always refused to talk about them, you know, Ma dear.”[15]

The secret Mrs. Loving was burdened with and the impetus for the family’s northward move was that her oldest child and her husband, “were lynched!!”[15] From this point in the play, Tom and Rachel begin to change. While Tom begins to dwell on a life lacking opportunity, Rachel begins to envision the pain of motherhood as an African American woman:

“Then, everywhere, everywhere, throughout the South, there are hundreds of dark mothers who live in fear, terrible, suffocating fear, whose rest by night is broken, and whose joy by day in their babies on their hearts is three parts pain.”[16]

At a time when homemaking was idealized, Rachel shuns marriage and motherhood, seeing them both as paths to despair that comes with raising children in a racist society.

Grimké submitted “Rachel” to the Drama Committee of the NAACP, which decided to stage the play in Washington, already a center of African American progress and potential. On March 3, 1916, the curtain was raised at the Miner Normal School, a teachers college for African Americans founded by abolitionist Myrtilla Miner.[17] With a cast of local, African American thespians, the NAACP touted the production as “The first attempt to use the stage for propaganda in order to enlighten the American people relative to the lamentable condition of the millions of Colored citizens in this free republic.”[18] Though neither The Washington Afro-American nor The Washington Bee (Washington’s preeminent black newspapers of the day) seemed to have offered an assessment the play, The Evening Star found "Rachel" to be "a strong play" but one "full of pessimism."[19] (The assessment was likely a nod to Rachel’s rejection of a suitor and motherhood "in the belief that her having children would only provide more black people for whites to lynch."[20]) After an additional performance on Saturday March 4, 1916, the play was "staged twice afterward" in Boston and New York with the original Washington cast before fading into obscurity.[21]

"Rachel” would finally receive its deserved attention, garnering critical acclaim after it was published as a book in 1920.[22] Mary White Ovington, suffragist and NAACP vice-president,[23] celebrated the story, calling it a “beautiful piece of art and we hope will mark the beginning of a series of great dramatic works by colored writers.”[24] This praise from Ovington is a testament to the play’s success.

Grimké wrote the play not only to condemn racist violence but also as an appeal to white women who she viewed as complicit. "If I could reach their hearts," Grimké wrote later, "then perhaps instead of being active or passive enemies they might become, at least, less inimical and possibly friendly."[25] Ovington, herself a white woman, saw enormous potential for Grimké 's play to do just that. "It has made its readers think and that after all is the most important thing that a book can do."[26] Poet William Stanley Braithwaite went even farther, declaring that in drama, "nothing has been achieved [by African Americans] with the exception of Angelina Grimké’s 'Rachel.'"[27]Braithwaite’s praise may seem exceedingly high today but considering when it was written, 1924, the impact of "Rachel" becomes real.

It is rather cliché to refer to someone as being ahead of their time, but such was the case with Angelina Weld Grimké.

Footnotes

- ^ Archibald and Francis Grimké were born into slavery.

Perry, Mark. “Lift Up Thy Voice: The Grimké Family’s Journey from Slaveholders to Civil Rights Leaders.” Viking Press: New York, 2001. - ^ “Broke All Stage Records.” The Washington Post, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers) January 30, 1916, p. SM2.

- ^ https://www.history.com/news/kkk-birth-of-a-nation-film

- ^ Agarwal, Kritika. "Monumental Effort: Historians And The Creation Of The National Monument To Reconstruction." Perspectives on History, January 24, 2017, https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on…, Andrew. "W.E.B. Du Bois's 'Black Reconstruction' and the New (Marxist) Historiography." U.S. Intellectual History Blog, November 1, 2017. https://s-usih.org/2017/11/w-e-b-du-boiss-black-reconstruction-and-the-…, Dylan. “Woodrow Wilson was extremely racist — even by the standards of his time.” Vox, November 20, 2015. https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2015/11/20/9766896/woodrow-wilson-racist

- ^ “Movies At Press Club.” The Washington Post, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers) February 20, 1915, p. 5.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Birth Of A Nation Arouses Ire Of Miss Jane Addams.” The Chicago Defender, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers) March 20, 1915, p. 1.“Eugene V. Debs Flays Big Movie.” The Chicago Defender, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers) January 15, 1916, p. 1.

- ^ “Race Riot At Theater.” The Washington Post, April 18, 1915. p. 2.T rotter was later acquitted “Monroe Trotter and Dr. Puller Are Acquitted: New England Defender.” The Chicago Defender, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers) May 8, 1915, p. 1.

- ^ “Victory For Film Play: Illinois Superior Court Gives O.K....” The Washington Post, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers) June 27, 1915. (ProQuest Historical Newspapers), p. SM2.

- ^ The Crisis: A Record Of The Darker Races, Vol. 4, Number Five, September 1912, p. 256. https://books.google.com/books?id=D1oEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA248&dq=auto-da-fe&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjPs9jOrp3hAhVCp1kKHU_QDlMQ6AEIKjAA#v=onepage&q=attack%20segregation%20laws&f=false

- ^ “The Burden.” The Crisis: A Record Of The Darker Races, Vol. 3, Number Five, March 1912, p.209https://books.google.com/books?id=J1oEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA209&dq=lynched+without+trial&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjDqOD0uZ3hAhWEq1kKHRhOB7sQ6AEIMjAC#v=onepage&q=lynched%20without%20trial&f=false “The Burden.” The Crisis: A Record Of The Darker Races, Vol. 2, Number Six, March 1911, p.254https://books.google.com/books?id=I1oEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA253&dq=lynched+without+trial&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiIqbCxup3hAhVRjlkKHRmfCcYQ6AEINjAD#v=onepage&q=lynched%20without%20trial&f=false

- ^ Woodley, Jenny. Art for Equality: The NAACP’s Cultural Campaign for Civil Rights. University Press of Kentucky, 2014.https://books.google.com/books/about/Art_for_Equality.html?id=8umKAwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button#v=onepage&q=crisis%201911&f=false

- ^ Grimké, Angelina Weld. “Rachel: A Play in Three Acts.” The Cornhill Company: Boston, 1920.https://books.google.com/books/about/Rachel.html?id=UpA0AAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ^ Ibid., p. 22.

- ^ Ibid., p. 23.

- ^ Ibid., p. 28. https://books.google.com/books/about/Rachel.html?id=UpA0AAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ^ Nolan, Rachel. “Uplift, Radicalism, and Performance: Angelina Weld Grimké’s Rachel at the Myrtilla Miner Normal School.” Legacy: A Journal of American Women Writers, Vol. 35, Number 1, 2018, p. 1-24. Whites training to become teachers in Washington, D.C. attended the separate, James O.Wilson Normal School until 1955 when both, colleges, blocks away from each other merged.https://www.udc.edu/about/history-mission/

- ^ “Colored Cast to Present Race Play.”Evening Star (Library of Congress) March 1, 1916, p. 15Woodley, Jenny. Art For Equality: The NAACP’s Cultural Campaign For Civil Rights. University of Kentucky Press: Kentucky. p. 102.https://books.google.com/books?id=G9yJAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA50&lpg=PA50&dq=art+for+equality+propaganda&source=bl&ots=tKnspIhuSO&sig=ACfU3U3udcDNshE2RcMCHrbojqk5hp5zQg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj7lND3vpbhAhVIw1kKHctAAu0Q6AEwDXoECAgQAQ#v=onepage&q=rachel%20propaganda&f=false

- ^ “ ’Rachel,’ A Race Play Given By Local Cast.” Evening Star, (Newspapers.com) March 4, 1916. p. 15.

- ^ Perry, Mark. “Lift Up Thy Voice: The Grimké Family’s Journey from Slaveholders to Civil Rights Leaders.” Viking Press: New York, 2001. p. 338.

- ^ “Plays and Players.” New York Tribune, (Newspapers.com) April 26, 1917. p. 11.

- ^ Herron, Carolivia, “Selected Works of Angelina Weld Grimké.” Schomburg Library of Nineteenth-Century Black Women Writers: New York, p. 5.https://books.google.com/books/about/Selected_Works_of_Angelina_Weld_Grimk%C3%A9.html?id=qqpsu--hd5EC&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button#v=onepage&q=blackness%20closing%20door&f=false

- ^ Archibald Grimké also served on the team of vice presidents with Mary White Ovington.https://books.google.com/books?id=_1kEAAAAMBAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=the+crisis+magazine+1915&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj41q-Rq5bhAhWOpFkKHbnTAD04ChDoAQgzMAM#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ^ Ovington, Mary White. “Book Chat— ‘Rachel’.” Richmond Planet, December 17, 1921. (Newspapers.com) p. 4.

- ^ Nolan, Rachel. “Uplift, Radicalism, and Performance: Angelina Weld Grimké’s Rachel at the Myrtilla Miner Normal School.” Legacy: A Journal of American Women Writers, Vol. 35, Number 1, 2018, p. 1-24.Tate, Claudia. Domestic Allegories of Political Desire: The Black Heroine’s Text at the Turn of the Century. Oxford University Press, 1992. p. 219.

- ^ Ovington, Mary White. “Book Chat— ‘Rachel’.” Richmond Planet, December 17, 1921. (Newspapers.com) p. 4.

- ^ “Books And Their Makers.” The New York Age, (Newspapers.com) August 30, 1924. p. 4.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)